The AHA has vigorously opposed legislative efforts across the nation to discourage, harass, and threaten US history teachers by limiting the use of particular words, ideas, concepts, and sources. This legislation rests on assumptions about what is being taught in our nation’s classrooms and narrow-minded notions about what should be taught. The AHA’s work has focused on principles of academic freedom, support of the professional integrity of our members and colleagues, and careful evidence-based arguments that reflect consensus among nearly all professional historians. What has been missing is evidence regarding the very premises of the legislation and the rhetoric surrounding it. In reality, what does the secondary US history curriculum look like? And what do teachers actually bring to their classrooms?

We now have that evidence.

First, however, as a historian obsessed with context and inclined toward narrative modes, I’ll explain how we got here. Everything has a history, including the AHA’s Mapping the Landscape of Secondary US History Education initiative.

In 2020, the now former president of the United States used Mount Rushmore on the Fourth of July as a backdrop to accuse our nation’s teachers of professional malfeasance, intellectual dishonesty, and betrayal of our patriotic responsibilities. “Our children,” he said, “are taught in school to hate their own country and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes but that were villains. The radical view of American history is a web of lies—all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.”

Beyond anecdotal evidence, no one actually knew what was happening in classrooms.

On that September 17, Constitution Day, his administration hosted the White House Conference on American History to expand and deepen this allegation, legitimating it by using the National Archives building to formally host the conference but with no input or participation from the agency’s staff. The AHA, in a statement signed by 46 scholarly organizations, deplored the conference’s distorted caricatures of history education as a “tendentious use of history and history education to stoke politically motivated culture wars.”

This, too, has a history. A decade ago, I explained in an op-ed that the “debate over what is taught in our schools is hardly new.” A substantial historiography—including books by Frances FitzGerald, Diane Ravitch, Jonathan Zimmerman, and Donald Yacovone, among many others—explains the long history of conflicts over how we teach our nation’s past. But in recent years, something new has happened: state legislators began introducing laws prohibiting use of the materials and concepts that were denounced in the September 17 conference and the subsequent President’s Advisory 1776 Commission report. Although the newly elected president withdrew that report immediately upon taking office in January 2021, it has lived on in legislation. Bills introduced in legislatures across the country refer to “divisive concepts” that must be stricken from history classrooms, usually including critical race theory and specific resources such as curriculum materials produced as part of the New York Times’ 1619 Project.

Most of the legislative action and administrative mandates initially focused on secondary schools—although with important implications for higher ed as well. I described this landscape in my September 2022 column, and the AHA’s letters and statements have intervened in 22 states, emphasizing the legislation’s impact on the quality of history education and the importance of teachers’ professionalism. We had not, however, been able to address the essential premise of the legislation: that teachers are introducing critical race theory or other concepts specified in these bills. Nor had we been able to say what materials teachers actually use in their classrooms. There was no factual basis for the contentious debates over history education that have attracted attention from state legislators, school boards, parents, and media across the country. Beyond anecdotal evidence, no one actually knew what was happening in classrooms in different parts of the country. Lots of heat, not much light.

Until now.

An AHA research team has read social studies standards for every state and interviewed hundreds of teachers and administrators. Over approximately two years, these four historians—Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Nicholas Kryczka, and Scot McFarlane—have collected instructional materials from districts, teachers, and publishers. This documentation includes urban centers, suburbs, small towns, and rural districts. To find out what teachers are actually doing in their classrooms and how they prepare for that work, we contracted with the National Opinion Research Center to survey thousands of middle and high school US history educators across a sample of nine states.

Our key finding is clear: if a typical American history classroom exists, its teachers generally are not framing our nation’s history in the specific ways targeted by “divisive concepts” legislation. They are not teaching their students to hate their country, their grandparents, or their peers whose backgrounds and identities differ from their own. If teachers are emphasizing the significance of racism to the history of the United States, it is because most professional historians agree that ideas about race have been among the most important forces in shaping the American past.

Nor are a critical mass of teachers mired in the white supremacist traditions of historians William Dunning or U. B. Phillips, as some critics continue to allege. The resources they consult, the materials they use, and the assessments for which they prepare their students all indicate that students learn histories different from what their grandparents—and in some cases even their parents—might remember.

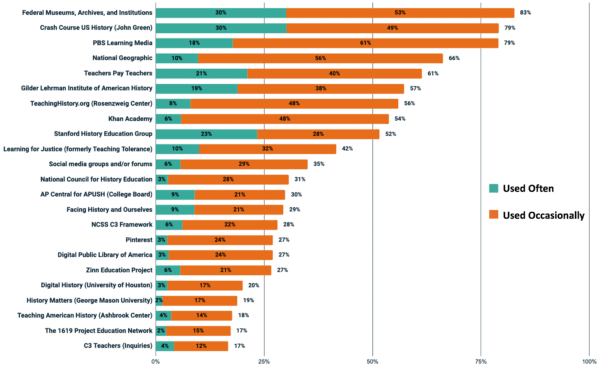

Moreover, most teachers are drawing materials from sources that are hardly deeply politicized, whether from the left, right, or some other angle. Consider where secondary school teachers in our survey go to for information and lesson plans (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Top no-cost resources identified by teachers. AHA research data

The AHA neither denies nor ignores challenges in secondary school history education that prompt some college and university instructors to lament the preparation of incoming students. But we also are confident that what matters most is preparation, not “indoctrination.” Our teachers don’t need legislators passing laws that led one Florida teacher to tell us in a conference session, “I don’t know what I can say anymore.” They need legislators who will appropriate funds for history-rich professional development that feeds teachers’ desire to be better historians. District-driven professional development focuses largely on pedagogy and technology; teachers need more content-oriented resources.

Legislators and others worried about indoctrination should focus on what they can do to help, rather than hurl unsupported allegations. Sure, there are activist teachers who cannot resist the lure of the classroom pulpit. There are school districts whose teachers and boards of education are steeped in ideologies infused with political commitments and a narrow-minded determination to shape a citizenry in their own image. But “indoctrination”? Anyone who has much contact with teenagers is likely aware of the difficulty of indoctrinating a teenager. I can’t resist a comment attributed to San Francisco city council member Harvey Milk nearly a half century ago: “If it were true that children mimicked their teachers, you’d sure have a helluva lot more nuns running around.”

For preliminary findings from the AHA’s Mapping the Landscape of Secondary US History Education, see the recording of the webinar American Lesson Plan on the AHA’s YouTube channel and “Culture Warriors—on Both Sides—Are Wrong about America’s History Classrooms” in Time. The first extensive report will be issued in fall 2024.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.