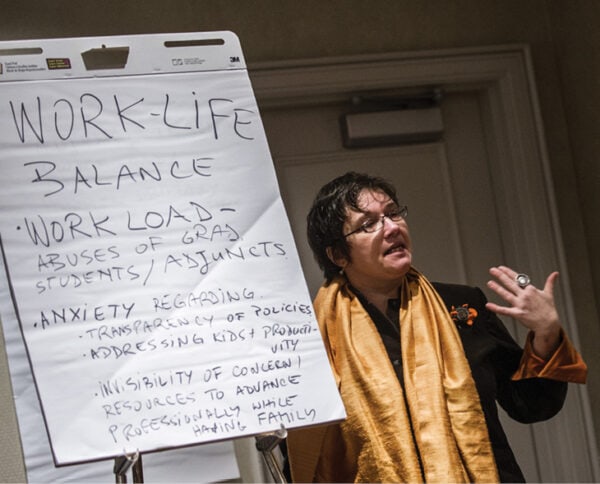

This January I spent a morning at the AHA annual meeting with a group of remarkable women in a conversation about the state of work-life balance in academia.1 Their concerns echoed the anxieties of a generation (those who have recently defended or are about to defend their dissertations) that has come of age in the period of recovery from recession and fewer tenure-track positions in academia. They were all mothers, often of more than one child. They were smart, articulate, passionate, and ambitious. They were hopeful and fearful. They were frustrated. What they were not is naive or unaware of the complexities and difficulties of entering academia in today’s world.

For those who wish to pursue life at its fullest—a career, a long-term relationship with another person (let’s call it marriage, for convenience), and motherhood (by whichever means one becomes a mother)—these women told the same story: their ability to negotiate among demands in all parts of their lives is hampered by work environments that ultimately do not respect, much less support choices for anything other than complete devotion to the workplace. This structural problem demands our attention and thoughtful responses.

That is not to say that some universities and history departments do not attempt (or even succeed) in providing some support, such as parental leaves, health-care benefits, and even subsidized child care. There are wonderful examples of best practices. But the same individuals who spoke of such easements also remarked on the difficulty of finding sympathetic ears among their committee members (men or women), advisers (men or women), and overall their department when it came to making decisions about starting a family; writing dissertations while going through a pregnancy; going on the job market while nursing an infant; or crafting new research projects while raising small children.

Maria Bucur at the Committee on Women Historians brainstorming session at the AHA 129th annual meeting. Credit: Marc Monaghan

I heard over and over about the unease and even fear of approaching one’s senior colleagues or thesis advisers about such topics, even at the point of looking very pregnant. I was surprised to hear this happened even when the senior colleagues or thesis advisers in question were themselves parents. Why is it that we don’t address these issues as a basic element of our workplace? There are, of course, legal boundaries that prescribe what someone can ask of a job candidate. There are also ethical and legal limits to the sorts of questions faculty may ask students. But there is a difference between what the law requires and how people choose to behave in real-life situations.

We live in a time when more women than ever before are enrolled in graduate programs, having become a majority of graduate students overall (1.7 million women to 1.2 million men in 2012).2 These women are pursuing their degrees at a time when they are most likely to become mothers. That is simply a fact. Our profession is significantly marked by this shift, and all of us need to process it as part of our work environment and mentoring responsibilities.

Women still bear a disproportionate responsibility in parenting young children. Women ages 35 and younger do a lot more of the heavy lifting when it comes to sleep deprivation, multitasking, and crisis management, all of which mean fewer opportunities to be professionally productive for a prolonged period of time, as any parent knows.3 While I dream of a day when men become more equitably involved in these stressful responsibilities, we are not there yet. So while we work to make that change happen, we also need to simply acknowledge that our junior female faculty and graduate students have different choices before them than junior male faculty when it comes to work-life balance.

If we are willing to acknowledge this fact, then we need to ask ourselves: What are our responsibilities toward these colleagues and students; what can we, as professionally secure senior colleagues, do to level the playing field? I asked myself this question 11 years ago, when my second son was born. I volunteered my time on campus-wide committees that could become a vehicle for changing the family-leave policies, and after seven years of working on these issues together with other women and men dedicated to this cause, I saw our university policy change to treat faculty (though not yet adjuncts) with the dignity that each person should be entitled to as a matter of course.4 Graduate students also started to receive better treatment as a result of this precedent, from health-care benefits to parental leave, without losing university funding. Our next challenge is to address the lack of access to such benefits on the part of adjunct faculty and staff who do not benefit from other similar policies, such as paid time off.

Where does such service fit in our tenure system? Nowhere. That is why I made sure my first monograph was off to the press before I started on this path. I am not asking the impossible of people who are vulnerable. But those of you who have joined the ranks of tenured faculty do need to ask yourselves what sort of work environment you want to be part of, and how you can bring about change when various kinds of inequity abound. There are many causes to support, but none as urgent: If the majority of graduate students are women and if these women are to be treated with all the respect they deserve as human beings, inclusive of the desire to become a parent, while they are our junior colleagues or graduate students, is it not imperative that we all do some soul-searching and make the effort, formally unrewarded though it may still be, to enable these junior scholars to succeed in their ambition to be both successful historians and also parents?

Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Train and engage with questions about parenting in your graduate programs. The director of graduate studies may not be comfortable with such a role, but someone who is should be both designated as an initial point person and made available to the students. Such assignments should also be recognized as valuable service by department chairs and the faculty at large. An effective chair could figure out these assignments and advocate with the higher administration that such service is necessary and should be valued appropriately by the university.

- Work with your deans and provosts to develop and maintain humane policies about graduate student funding and health care in matters of parenting. This should not be something done in secrecy; rather, it should be advertised as important to all faculty. There are good examples out there for best practices; this is not an unprecedented innovation.

- Be willing to have uncomfortable conversations about starting a family when your graduate students broach the subject.

- At the point of recruiting, though you may not ask about personal questions such as “Do you plan to start a family?” welcome the opportunity to speak about such issues when interviewees bring them up. It takes courage and honesty on their part to do so, and they are giving you an opening. If they are willing to trust you, please respect their desire to be both parents and colleagues.

- Mentoring of junior faculty should take into account such work-life balance issues, and you should think comprehensively about where they fit in relation to other aspects of mentoring junior faculty. The same senior faculty member may not be ideal as both scholarly and work-life balance mentor, but there are some of us willing to do that sort of work because it is valuable to both junior faculty and to our work environment overall.

- If your family-leave policies (connected to birth/adoption, as well as caretaking in relation to adults, not just infants) are spotty, look around for best practices and make that a priority for your faculty senate. Reward those who work on behalf of such change as important professional service work.

- Do not ignore the burden of child or adult care when it comes to scheduling talks, classes, and other professional events in your department. Everyone has a story, I’ve been told, when it comes to wanting to teach at a certain time or scheduling job talks and department meetings. But no personal preference is as pressing as the daily burden of taking care of someone who depends primarily on you. Chairs can play an important role in navigating such issues thoughtfully and gracefully.

- When people take family leave, their productivity for that period of time should not be evaluated by departments and outside reviewers with the same expectations as the productivity of colleagues who have not been on family leave. While this sounds obvious, it is an issue that makes the person being evaluated vulnerable and quite uncomfortable. Chairs need to make the modified expectations clear to both internal and external evaluators.

Such steps should help change university cultures around the uncomfortable issue (especially for women) of striking a balance between becoming a successful historian and colleague in academia and being a parent.

Notes

1. I would like to thank the members of the Committee on Women Historians and Philippa Levine for their comments, as well as the junior colleagues who have inspired me to write this.

2. National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 105.20: “Enrollment in Educational Institutions, by Level and Control of Institution, Enrollment Level, and Attendance Status and Sex of Student: Selected Years, Fall 1990 through Fall 2023,”

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_105.20.asp.

3. In 2011 the female-to-male ratio was 18/10 for housework and 14/7 for child care in numbers of hours per week, “Modern Parenthood,” Pew Research: Social & Demographic Trends, March 14, 2013,

https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/03/14/modern-parenthood-roles-of-moms-and-dads-converge-as-they-balance-work-and-family/.

4. For those interested in the Indiana University family-leave policy, please see Indiana University, Bloomington, Academic Guide, “Indiana University Paid Family Leave Policy for Academic Appointees,”

https://www.indiana.edu/~vpfaa/academicguide/index.php/Policy_F-4.

Maria Bucur is John V. Hill Chair of East European History at Indiana University and author of several books, including Heroes and Victims: Remembering War in Twentieth-Century Romania (Indiana University Press, 2009). She is completing a book entitled The Birth of Democratic Citizenship: Women and Everyday Life in Socialist and Post-Socialist Romania. She currently serves as the chair of the AHA Committee on Women Historians.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.