Middle school teachers know that our students are often ready to take on the world’s problems. Their hunger for social action is inspiring and offers opportunities for teachers to foster meaningful learning experiences in the classroom.

Creating their own podcasts allowed ’s seventh-grade students to explore the women’s history left out of their textbook. Courtesy Bridget Riley

I had such an experience when planning a seventh-grade revolutionary-era unit. I am not one to teach to the textbook. However, having heard my students take note of the discouraging lack of women in our US history textbook, I made our textbook the entry point for student project work. In class, we counted: it was 47 pages into a 55-page chapter before the contributions of women during the revolutionary era were addressed in more than a sentence or two. The textbook, published in 2019, annexed women’s history with two other paragraphs at the end of the chapter: “How African Americans Served in the War” and “American Indians Choose Sides.” As an educator, I was ready to move beyond the “just add women [and racial and ethnic minorities] and stir” approach.

This experience drove home a reality that I had grappled with as both an educator and a historian. All too familiar to anyone who teaches K–12 history, it is also a problem that has long been the focus of many academic studies. Namely, when students in grades K–12 study history, they are often confronted with a nearly womanless past, one where white male military and political figures populate the pages of our textbooks while women, especially women of color, are cast only as supporting actors.

When I began working at an all-girls school, this reality took on a new meaning for me. A central part of the school’s mission is to inspire girls to work for justice and to take on leadership roles. What are the implications for my female students who see the dearth of women in the textbook? What message does it send to students of color when American history is framed almost exclusively around the accomplishments of white men in politics? How did my students, many of them precisely at an age when experts suggest confidence can dramatically decline in adolescents, internalize this absence of women and relate it to their own place in the world?

When students in grades K–12 study history, they are often confronted with a nearly womanless past.

Despite the push to remedy gender imbalance in social studies standards and textbooks at a national level, as well as an understanding of the negative impacts of a curriculum that is not representative of a diverse student body, change has been slow. Often, curricular change originates from within the classroom. I implement change by framing my American history course so that students encounter the past through diverse lived experiences, emphasizing stories that too often go untold and challenging narratives that are little more than nostalgia. I want them to see that studying the past does not mean focusing only on the accomplishments of men in politics. Rather, the daily experiences of ordinary individuals, of all races and identities, compose the real treasure trove of historical information.

To accomplish this in my Revolutionary War unit, I turned to the project approach, a style of project-based learning that defines a project as an in-depth investigation of “a real-world topic worthy of a student’s attention and effort.” The teacher’s role here is to provide context, support student exploration and curiosity, provide feedback and opportunities for collaboration and connection among students, and confer with students in small groups and whole-class settings. Rather than a traditional piece of written analysis, I asked students to create a podcast to showcase their research. A student-created podcast would amplify not only the voices of those who have gone unheard in our history textbooks but also the voices of the students themselves.

We began by exploring the topic of representation broadly. Students considered differences in how women and men are represented in history and how that representation shapes gender roles today. As a class, we thought through a fundamental question: What were we missing when we did not hear the voices of white women, Black Americans, Asian Americans, Indigenous Americans, and many others? Next, we created a planning web to formulate guiding open-ended inquiries. What effect did a woman’s race, ethnicity, and social class have on her experiences during the revolutionary era? Although women were banned from voting and holding office, how did they shape the outcome of the Revolutionary War? Did freedom and liberty mean the same thing for white male colonists as it did for white women and women of color? From our list, each student selected one guiding question to frame their research and focus their podcast episode.

I wanted students to avoid creating podcast episodes that resembled a book report or biography. Instead, their episodes had to demonstrate the historical thinking skills they had developed throughout the course of the year. Anchored in an exploration of primary documents, the podcasts showcased their ability to contextualize and corroborate historical sources in order to demarginalize women from our study of the past. The project called on students to consider how to examine an open-ended inquiry and how to identify and address a gap in the field of history. The process of researching, writing, scripting, revising, and producing allowed this project to be a pathway for understanding how historians work.

Podcasts showcased the students’ ability to contextualize and corroborate historical sources.

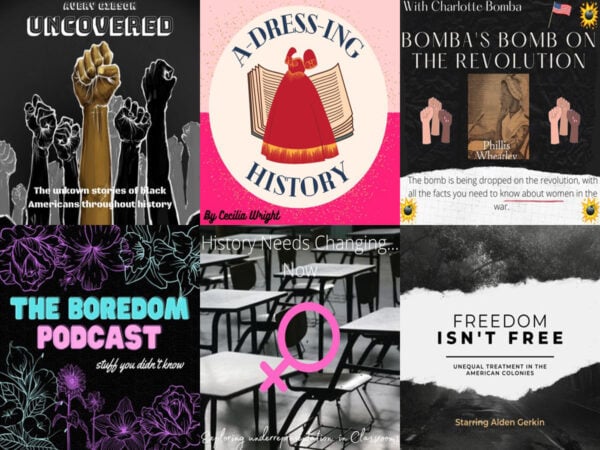

The final podcast episodes were as varied as one might imagine. While each student started with the same premise—to provide a solution to underrepresentation and gender imbalance in our textbook—their individual episodes created a kaleidoscope of voices and perspectives (and sometimes middle school candor). Emerging from this process was a general unpacking of identities and intersectionality. Many students were inspired to examine not only how gender shaped a woman’s experience and voice but also the impact race might have had on her experiences. So students began to appreciate how gender and race are intersecting layers of identities—for the women of the past and for themselves and the people around them. By focusing on how both gender and race shaped an individual’s experience, students could further understand how access to resources for one person could be linked to the denial of resources from another and how, just like individuals in the past, their own layers of identity help to shape who they will one day become. Teaching and learning at the intersections of race and gender offered students an opportunity to examine and affirm their own identities and the identities of others, past and present.

One student centered her exploration on the experiences and writings of Black preacher and abolitionist Mary Perth. In her episode, she framed Perth’s fierce belief as a form of resistance as the Methodist Church splintered over the issue of slavery: “Since Mary was both a woman and an enslaved woman,” my student commented, “she couldn’t hold official [religious] services. So you know what she did? She gathered her fellow enslaved in the woods, late into the night, in order to preach to them. Religion was so important to this woman that she walked miles just to preach. Think about that.” This student then critically examined a general dearth of written sources from Black women, the majority of whom were legally prevented from reading and writing. She shared how the particular combination of identities for women like Perth multiplied their obstacles, making their determination and resilience stand out all the more. For my student, Perth was not an avatar for the accomplishments of Black women in the revolutionary era, as might have appeared in the pages of our textbook. In the process of researching, scripting, and recording her podcast, my student had listened to the human story of this woman in hopes that others might listen and hear her story as well.

As I prepare a new cohort of seventh graders for this project, I will do a few things differently. First, as a part of a new curriculum, students have already spent time exploring identity and building social comprehension in their advisory program. I hope to embed some of this important work into their project, thereby further extending the critical conversations surrounding identity to their historical thinking work. Second, I plan to carve out more time and space for student research and exploration. This phase of inquiry-driven research was the most fruitful time not only for students to gain a sense of autonomy over their learning but also for me to confer with them individually and in small groups as they refined their historical analyses. Finally, recognizing that learning is social and that children learn among and with their peers, I plan to implement a more intentional process for peer review, beginning with the initial phases of research and lasting through podcast production and editing. Partnership with a trusted peer, both for whom and from whom meaningful and generous feedback is generated, is precisely the kind of experience historians of all ages should have.

Bridget Riley teaches middle school history at Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart in Bethesda, Maryland.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.