This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Coordinating Council for Women in History (CCWH). Although the CCWH as we know it today came together in 1995, its story begins in December 1969, at the annual meeting of the AHA.

The 2017 Women’s March in Washington, DC. Mobilus In Mobili/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Over two dozen historians, led by Berenice A. Carroll, had been circulating a petition to press the AHA to take action to improve the status of women historians. The AHA Council responded by appointing members of the first Committee on the Status of Women at that December meeting.[1] This was seen as a step forward but not a substantial move, since the AHA remained a male-dominated organization. It was therefore important to start and sustain a group that could advocate for women in the discipline. For 50 years, the CCWH has done just that.

Coming Together

That 1969 AHA meeting has been mythologized, mostly for challenges to the profession from antiwar and radical historians, many (though not all) of whom were men.[2] But the activism of 1969 also included a women’s caucus meeting that saw the formation of a new group, the Coordinating Committee of Women Historians in the Profession (CCWHP). Its goals were to recruit more women into the profession, to alleviate discrimination against women students and faculty, to secure greater inclusion of women in AHA annual meetings and committees, and to encourage the growth of women’s history through teaching and research. Two days after the caucus meeting came a panel that did not appear on the program. Initiated by Hilda Smith, its subject was the status of women in history. The room, Smith later recalled, was packed.[3]

As the CCWHP grew, other groups were founded that promoted women’s history and women historians, including the Conference Group on Women’s History (CGWH), created in 1974, and several regional associations. These organizations had many overlapping members. In 1995, the memberships of the CCWHP and the CGWH voted to merge into one group, becoming the CCWH.[4]

Two days after the 1969 women’s caucus meeting came a panel on the status of women in history. The room was packed.

Last year, when the CCWH marked the life and passing of Berenice Carroll, we reflected on her work as a pioneer of women’s rights and women’s history. Carroll’s work not only offers us a rich legacy, it also exemplifies the labor and success of the CCWH. Under her leadership, we created course bulletins, newsletters, and research progress reports, crucially mapping emerging scholarship and the state of the field, and reconceptualizing the very constitution of history.[5] The work of creating women’s history, Carroll reflected, was academic, to be sure; yet to deny that such labor was also activism was to make marchers or boycotters the only legitimate image of activism. The struggle “to change history—to change the profession of history, to change historical scholarship, and to change the direction of our own history”[6] was, to Carroll, inherently activism, for it demanded the “strength of both action and intellect.”[7] It still does.

Building Bridges

After its organizational merger in 1995, the CCWH continued its work to center women as subjects of history and promote them as history professionals. This, as Nupur Chaudhuri and Mary Elizabeth Perry reflected in 1994 (on the occasion of the CCWHP’s 25th anniversary), required coalition building—an aspect of activism that can be both rewarding and precarious. Over the years, the CCWH built coalitions with other historical associations and scholars.

The CCWH inspired the Organization of American Historians and the AHA to create formal committees on the status of women in the profession and assisted in establishing them. Significantly, the CCWH encouraged the inclusion of women in the leadership of the AHA, and initiated and funded the AHA’s Joan Kelly Book Prize in Women’s History and Feminist Theory.[8] The CCWH organizes and co-sponsors panels for the annual meetings of the AHA and its affiliated societies, as well as for other groups, such as the World History Association and the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations. The Annual Awards Luncheon held at the AHA annual meeting showcases some of the most innovative new scholarship in all fields of history and provides a space for networking. The CCWH award committees also create service opportunities for our members, helping them build CVs and tenure files.

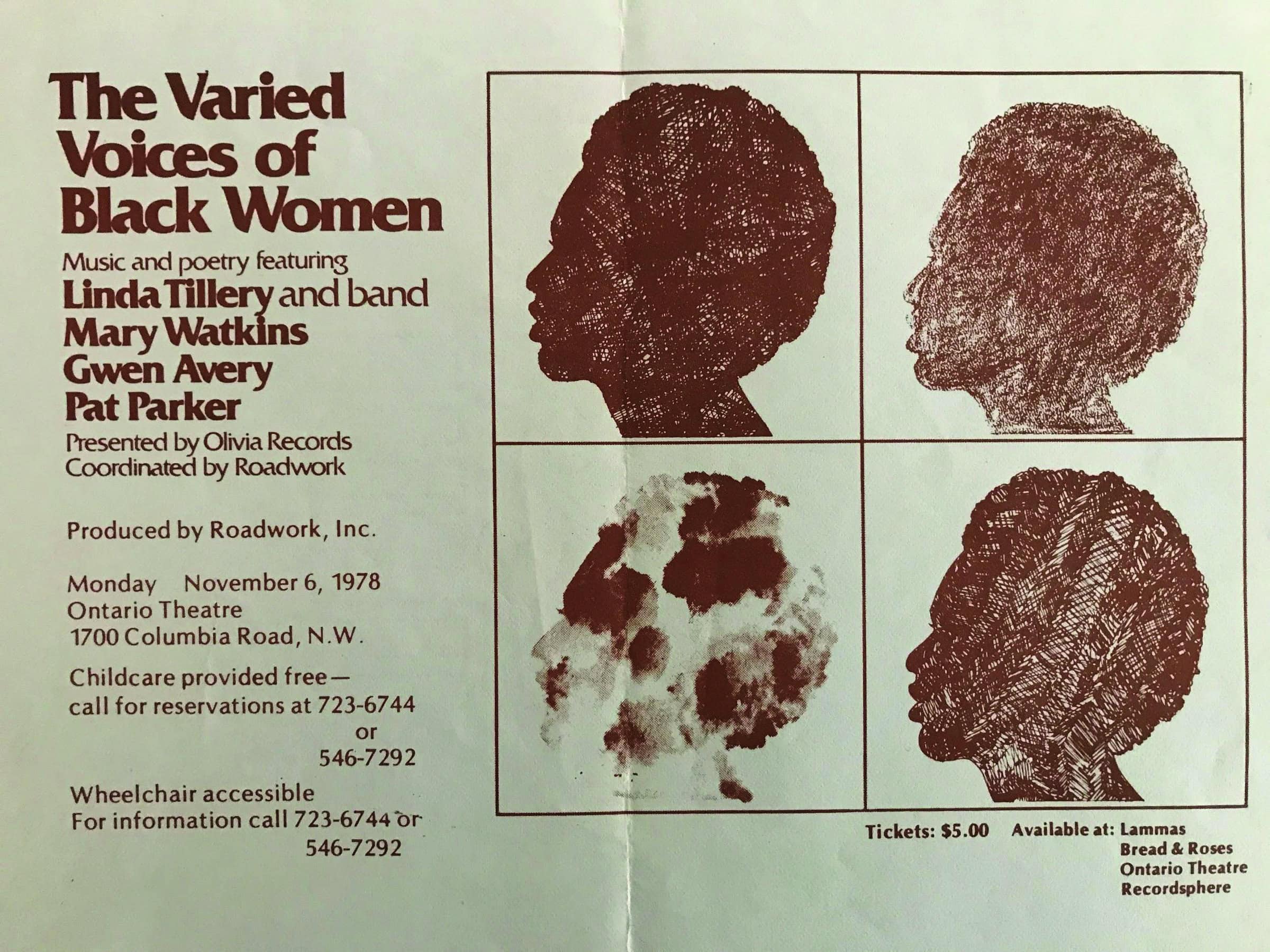

Courtesy the Coordinating Council for Women in History

We have met with and sponsored conference panels and celebrations with other associations (notably the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians), LGBTQI historians, African American women historians, environmental historians, and such regional associations as the Western Association of Women Historians and the Southern Association of Women Historians. The CCWH is also the United States representative to the International Federation for Research in Women’s History (IFRWH), which seeks to foster transnational scholarship and gender-justice solidarity. CCWH’s recent collaboration with IFRWH to pressure the Hungarian government to preserve academic freedom at the Central European University is representative of the broad nature of our work and its wider implications.

The academic world is denied the benefit of potentially cutting-edge research when a class of faculty has to struggle to pay the bills.

Activism in our discipline also includes mentorship, and some of the most important functions of the CCWH continue to be support for women in the profession. As Barbara Ramusack and Nupur Chaudhuri wrote in 2010, “This work proceeds within and beyond existing institutions.”[9] Indeed, through the energetic work of the CCWH Mentorship Committee, this takes place remotely in the form of e-mentorship sessions, as well as at regional and national conferences.

Precarity and the Future

The future of our intellectual work continues to depend on our activism. The history of women and gender is well established at some universities but endangered at others, for reasons that have a great deal to do with structural issues. Labor conditions are particularly troubling. The reliance on low-paid, part-time adjuncts led to a sense in the CCWH that contingent academic employment had become feminized; in turn, the group undertook a survey of its members on this issue.[10] In 2016, the late Rachel Fuchs, Adriana Bitoun, and Mary Ann Villarreal found that approximately 42 percent of the membership of the CCWH were adjuncts, with rates of pay that varied immensely. The adjuncts we surveyed teach at multiple institutions and prepare multiple new classes each year, and still find it difficult to earn enough to live.[11] The corporatization of American higher education continues to create contingent teaching positions, including adjuncts and postdocs, with few or no health or retirement benefits.

A soft academic job market means we all suffer—tenure-track and tenured faculty continue to carry out the same amount of committee work and service even as their percentage among the faculty declines. But more broadly, the academic world is denied the benefit of potentially cutting-edge research when a class of faculty has to struggle to pay the bills. One answer is definitely unionization, but addressing the problem also entails another form of coalition building: between tenured and adjunct faculty. Thus, precarious employment in the historical profession is a feminist issue. By lobbying departments and universities on behalf of endangered faculty, the CCWH fights against the marginalization and invisibility of women in the profession.

Activism in our discipline also includes mentorship, and some of the most important functions of the CCWH continue to be support for women in the profession.

Reflexive, intersectional work remains pressing in our time of rising totalitarian regimes, threats to academic freedom, limits on freedom of the press, and cuts to humanistic disciplines such as history, literature, philosophy, and women’s and gender studies. The specific issues addressed by our founding mothers a half century ago—invisibility and scorn for research on women’s and gender history and those who practiced it—have now been joined, and to some extent superseded, by new issues, including problems of workplace contingency, economic inequality, and racism.

Reflecting on the past, particularly a past as accomplished as CCWH’s, evokes nostalgia. Yet our many gains do not suggest we abandon our activism in the present and future. In fact, the awakenings of the 1960s—the movements for peace, civil rights, women’s liberation, free speech, and Black Power—which sparked and shaped the founding and activism of the CCWH, mirror many of today’s concerns. Academic issues of sexual harassment and assault; the absence and insufficiency of maternity leave; and inequality in the pay gap, administrative work, hiring, promotion, and tenure reflect the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements, as well as the struggles for reproductive justice and the rights of workers, children, LGBTQI people, Muslims, immigrants, and incarcerated people. The academy is a microcosm of the society in which it is imbricated. Organizing must take place despite the inevitability of critique (for example, on grounds of racial exclusivity); such criticism therefore must become a site of productive engagement that informs our work, both intellectual and activist.

As a multigenerational organization, the CCWH will face the next half century invigorated and inspired by our foremothers and prepared to confront the concerns of our newest members.

Notes

[1] Hilda Smith, “CCWHP: The First Decade,” in Hilda Smith, Nupur Chaudhuri, Gerda Lerner, and Berenice A. Carroll, History of CCWH-CGWH (CCWHP-CGWH, 1994), 7.

[2] Carl Mirra, “Forty Years On: Looking Back at the 1969 Annual Meeting,” Perspectives on History (February 2010).

[3] Smith, “CCWHP,” 8.

[4]History of CCWH-CGWH.

[5] Berenice Carroll, “Scholarship and Action: CCWHP and the Movement(s),” Journal of Women’s History 6:3 (Fall 1994), 79.

[6] Carroll, “Scholarship and Action,” 82.

[7] Carroll, “Scholarship and Action,” 83.

[8] Nupur Chaudhuri and Mary Elizabeth Perry, “Achievements and Battles: Twenty-five Years of CCWHP,” Journal of Women’s History 6, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 97–105.

[9] Nupur Chaudhuri and Barbara Ramusack, “The Coordinating Committee on Women Historians: Accomplishments and New Goals,” Perspectives on History (December 2010).

[10] Eileen Boris, Sandra Trudgen Dawson, and Susan Wladaver-Morgan, “Perspectives on Contingent Labor: Adjuncts, Temporary Contracts, and the Feminization of Labor,” Perspectives on History (May 2015).

[11] Rachel Fuchs, Adriana Bitoun, and Mary Ann Villarreal, “Results of the CCWH Survey Concerning Contingent Faculty,” Insights: Notes from the CCWH 47, no. 3 (2016): 6–11.

Sasha Turner is co-president of the CCWH for 2018–21. Barbara Molony is co-president of the CCWH for 2016–20. Sandra Trudgen Dawson is executive director of the CCWH for 2017–20.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.