Amid the recent hubbub about leaks and whistleblowers and Hillary Clinton’s rogue server, it has been easy to forget what a state secret actually is. Legal commentators and political pundits tend to think about state secrecy in the abstract terms of political philosophy. Perhaps secrecy is always undemocratic, appropriate only for absolutist or totalitarian states. Perhaps it is an unavoidable necessity in a hostile world—democratic governments find themselves forced to keep secrets to protect the security of the public. Or perhaps, if we follow Max Weber, secrecy is an essential trait of modern, bureaucratic governance.

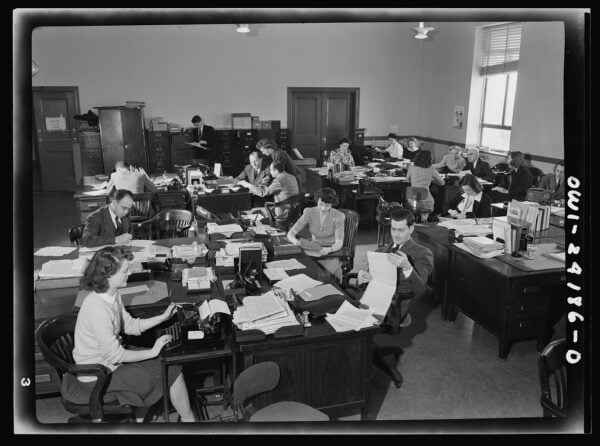

The Office of War Information (pictured above) created the Security Advisory board during World War II to coordinate government classification policies that would protect state secrets. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Whatever the truth of these broader musings, all of them make it difficult to remember that the “secrets” at stake in modern controversies were not dreamt up as thought experiments for political philosophy. They were produced by quite specific acts: the stamping of a document, the development of bureaucratic methods and logics of classification, the enforcement of physical and legal protections against prying eyes. State secrecy, in other words, should be understood as an institution. Which means that it has an institutional history.

In the United States, that history is remarkably short. The modern classification system was created in September 1951, in an executive order issued by Harry Truman. That order established the categories (Top Secret, Secret, Confidential) that are still used to keep information secret, as well as the rules and practices for classifying and securing information. Before this, the American government did not protect secrets in anything like the present form; secrecy had a different institutional character.

We can see this is through the history of the Security Advisory Board (SAB), an obscure, short-lived, and forgotten World War II organization. World War II witnessed the first efforts to establish classification practices throughout the federal government. In 1943, the SAB was created by the Office of War Information (OWI) to coordinate these new policies. As SAB representatives took stock of information security across the wartime administration, they discovered a remarkable lack of consistency. Federal employees were leaving classified information unlocked in buildings that made no effort to screen visitors. They were reading classified information on streetcars, proofreading classified information aloud in common areas, and taking classified information to unapproved commercial printing firms for reproduction. Federal employees did not yet know how to keep classified information secure—one clear sign that the practice was new.

Even more surprising than these frustrating lapses in security was the SAB’s realization that there was no clear law banning the unauthorized disclosure of classified information. To be sure, the Espionage Act of 1917 made it illegal to share information “related to national defense” with those who did not have authority to receive it. But during the drafting of the law in 1917, in defiance of what it saw as overreach by the Wilson administration, Congress had removed the sections of the act that established the process for defining what information was “related to the national defense” or how individuals were supposed to be authorized to access it. The legal penalties were thus undefined and orphaned—and they were not clearly related to the new classification systems now being promoted.

During World War II, both of these problems meant that the classification of information could not be relied on to secure secrets. Instead, journalists were asked by the Office of Censorship to voluntarily restrain from publishing information that might help the enemy. These requests were not backed by force of law, and while journalists could not be punished for publishing defense information, they nevertheless complied to a remarkable extent. But the system was a patchwork and an improvisation, and SAB members, fixated on unprecedented levels of security, began to press for stronger institutional guarantees.

In the waning stages of the war, the SAB thus began to draft general classification rules that would tighten the security of information both in practice and in law. When the OWI was abolished immediately after the war, the SAB was transferred to a joint State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, and continued its work on classification rules into the early Cold War. In 1951, Harry Truman issued those rules in Executive Order 10290, which established the modern classification system. The order fixed the problems the SAB had been concerned about during World War II. It created uniform definitions of secret information and standardized practices for handling that information. And it explicitly tied the new classification system to the previously orphaned sections of the Espionage Act, making it clearly illegal to share classified information with unauthorized persons.

Perhaps most importantly, the order gave individual government employees the institutional responsibility for classifying information. Whereas protecting secrecy during World War II had required the cooperation of the press, it now required only the action of the bureaucrat. Importantly, at the initial moment of classification, the government employee was instructed to consider only the risks that disclosure posed to national security. There was no requirement to consider the public’s right to know the information. When in doubt, a government employee was thus incentivized to overclassify rather than underclassify.

In 2014, there were a little under 50,000 original classification decisions. There were, however, 75.5 million derivative classification decisions, which could have been made by any of the 4.5 million government employees who have access to secrets.

The bureaucratic momentum created by this institutional structure has led to the steady expansion of state secrecy. Today, a little over 2,200 officials are “official classifiers,” who are responsible for classifying information in the first instance. That is a misleadingly small number, because the bulk of classification is officially “derivative,” which means that it is derived, in theory, from an original classification decision made by an “official classifier.” (The “original” decision can include such things as the preparation of a general guideline on classification; “derivative classification,” despite its name, is a capacious category that involves much initiative and discretion.) In 2014, there were a little under 50,000 original classification decisions. There were, however, 75.5 million derivative classification decisions, which could have been made by any of the 4.5 million government employees who have access to secrets. Since the 1950s, studies of the classification system by the defense and intelligence communities have repeatedly criticized this overclassification of information. But while subsequent executive orders have tinkered with the classification regime established in 1951, they have not fundamentally altered it. Today, complaints about overclassification are habitual.

It was not inevitable that the United States would establish this system of classification, and it was not the only way that it could have sought to secure state secrets. Congress, for instance, could have drafted legislation that asked classifiers to balance the need for secrecy against the need for public disclosure. So as we learn about leaks and security breaches today, we should not take the idea of “secrets” as a given. Rather than debating secrecy in abstract terms, we should remember that secrecy is produced by a particular bureaucratic mechanism, and ask whether what is being called “secret” deserves that label. There may always be some state secrets, but the current American secrecy regime was only constructed in the 1940s. When we remember that, it is easier to imagine changing it.

Established by the AHA in 2002, the National History Center brings historians into conversations with policymakers and other leaders to stress the importance of historical perspectives in public decision-making. Today’s author, , recently presented in the NHC’s Washington History Seminar program on “Free Speech and Unfree News: The Paradox of Press Freedom in America: April 11, 2016.” A video of his talk can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HX9D3SUzfK4

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Sam Lebovic is assistant professor of history at George Mason University, and author of Free Speech and Unfree News: The Paradox of Press Freedom in America(Harvard, 2016)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.