On June 27, 2024, Oklahoma state superintendent of public instruction Ryan Walters issued an order that “effective immediately, all Oklahoma schools are required to incorporate the Bible, which includes the Ten Commandments, as an instructional support into the curriculum” for grades 5 through 12. Nearly a month later, Walters followed up with guidelines for teachers, distributed via the Oklahoma State Department of Education website and on social media, that “must be provided to every teacher as well as providing a physical copy of the Bible, the United States Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Ten Commandments as resources in every classroom in the school district.” According to Walters, “These documents are mandatory for the holistic education of students in Oklahoma.”

Sincerely Media/Unsplash

The AHA issued a statement condemning these orders on July 9. “Oklahoma students deserve history education that is accurate and consistent with professional standards,” the AHA wrote. Seventeen peer organizations have signed on to this statement.

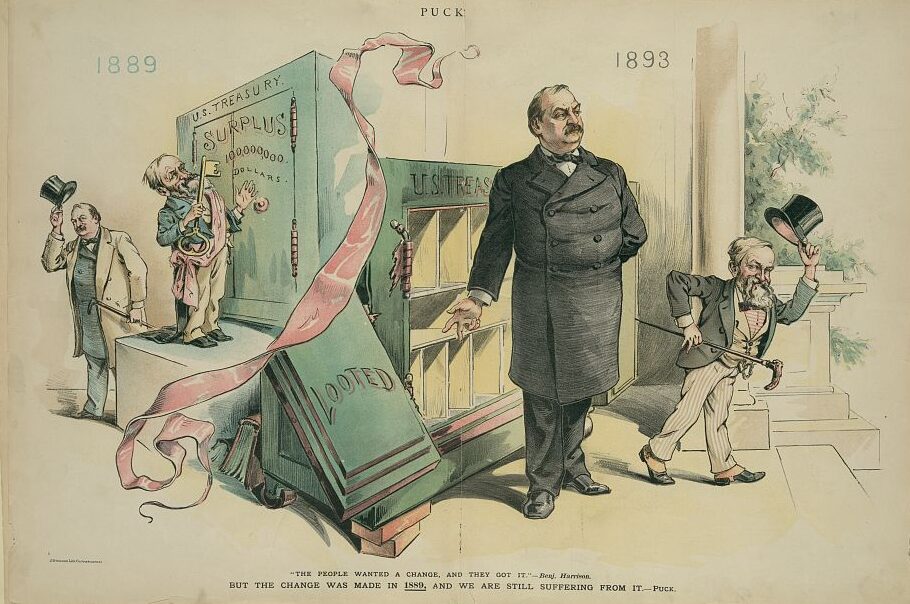

Historians addressed this mandate and related developments at an AHA webinar on July 26. In other states, including Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, state authorities have made significant claims about the relationship between the Bible and the nation’s founding. Recent legislation in Louisiana requires the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, including institutions of higher education. The Texas State Board of Education announced a major curriculum redesign that significantly expands attention to Biblical content in the K–5 English language arts and reading curriculum. Moderated by Jon Butler (Yale Univ.), the webinar panel focused on the historical roots of such mandates and guidelines and how they might affect social studies instruction in K–12 public schools.

Superintendent Walters claims that his mandate will not lead to indoctrination, proselytizing, or conversion efforts, and that teachers can incorporate views from other religions. But Walters did not stop with a mandate. On July 9, he announced an Executive Review Committee—including prominent right-wing activists such as Kevin Roberts of the Heritage Foundation and talk-show host Dennis Prager—whose mandate is to overhaul the history and social studies curriculum with an emphasis on “American exceptionalism.”

Implementation of such mandates is likely to be more complex on the ground.

As Butler noted in his introduction to the session, implementation of such mandates is likely to be more complex on the ground. “Bibles in the public schools have long been a fraught matter” in the United States. John Fea (Messiah Coll.) sees Walters’s order as straightforwardly opportunistic, given that his review committee includes Roberts, whose notion to advance American exceptionalism includes a move to “restore America to its Judeo-Christian roots.” And other than Roberts, Walters’s official social studies consultants do not include academic historians; no one else on the advisory committee holds a history PhD. Fea finds it difficult to believe there won’t be proselytizing, given a circle of advisors whose credentials rely more on connections to conservative movements and religious institutions than history or education.

In reading the guidelines, early Americanist Holly Brewer (Univ. of Maryland) found several troubling points. Discussion questions included in the guidelines reveal the assumptions of their authors. One states that “teachers must focus on how Biblical principles have shaped the foundational aspects of human society.” Students would benefit more from open-ended questions, Brewer observed, that consider the influences of other texts and philosophies, including the Enlightenment, on America’s founders. Because those founders were invested in the separation of church and state, Brewer noted that they would not have looked to the Bible to provide singular and definitive answers to fundamental questions. She also asked, If the Bible is mandated for every classroom and to be taught by all teachers, how will this come into play in math and science classes?

As Heath Carter (Princeton Theological Seminary) underscored, the Bible has been used throughout American history in support of injustice and inequality, so complexity is needed when discussing its influences. In both North and South, scripture was used to justify the morality of enslavement. Yet it was also used to justify the imperative of abolition. Butler added that in the 20th century, religious leaders quoted the Bible in support of Jim Crow segregation. Brewer also pointed to the ways the Bible was used to support the divine right of kings.

As Carter argued, critical analysis is an essential part of the historian’s work, yet these Oklahoma guidelines present an uncritical view of Biblical influence. Fea was reminded of the legacies of the American Bible Society, an organization that, since its founding in the 1810s, has emphasized that the Bible could “do its work” if you simply get people to read it. Perhaps, Fea surmised, that is what the designers of this policy are hoping for today.

Such a viewpoint falsely assumes that there is one interpretation of the Bible and one version of Christianity. According to Butler, the United States was “famously—sometimes infamously—pluralistic,” with multiple religions and multiple Christian denominations at its founding. The US Constitution itself was a unique founding document in how few references to religion it included. With a diversity of Christian denominations, Americans would read the Bible quite differently from one another. As an example, Butler pointed to differing interpretations between Quakers and other denominations on the question of women’s roles in society. Yet those differences within Christianity seem to be flattened in these kinds of mandates. When you require teaching “the influence of the Bible on the revolutionary or constitutional generation, or the Constitution, whose understanding of the Bible are we talking about?” he asked.

The US Constitution itself was a unique founding document in how few references to religion it included.

Walters’s mandate specifically mentioned threats to teacher licensure for noncompliance. “We’re entering a difficult stage here that has all to do with contemporary politics,” Butler said, “and a lot less to do with the teaching of history.” Fea agreed, noting that “teachers are not just passive entities in the classroom. We can trust their training” when it comes to thinking critically about the Oklahoma mandate. “The good teachers will see through this,” Fea said. “But then the question is what the consequences will be” for them.

Overall, the panelists encourage teachers and citizens alike to think critically about policies like the mandate to display the Ten Commandments in Louisiana schools. “Schools have always also been places of civic formation, a kind of moral formation,” Carter said. “And there’s an effort of folks, across state lines, to take the schools back.” Fea spoke directly to the teachers watching: “Whenever you have a document—in this case, the Ten Commandments—you’re asking: What is the document saying? But an extra part of the historical process has to be ‘What is the document doing?’ when you present it.” “That will be the question future historians have to unpack.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.