Transcription projects are everywhere these days. At Smithsonian, for example, digital volunteers are “volunpeers,” and universities are undertaking a great deal of work as well. At my own institution, Virginia Tech, Ed Gitre heads the American Soldier in World War II project, and Paul Quigley directs Mapping the Fourth of July. Transcription has even gained the attention of Buzzfeed, which posted “13 Things for History Lovers to Do Online When They’re Bored” in 2014. So I was surprised that none of the students in a first-year-experience (FYE) class I recently taught had ever participated, even informally, in such a project.

Virginia Tech students transcribing the World War I letters of Joseph F. Ware Sr. (pictured) became engrossed in his history. Joseph F. Ware Collection, Ms2010-022, Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blackburg, Va.

Virginia Tech mandated the creation of FYEs for freshmen and transfer students several years ago. In the history department, we first tried to sort out exactly what our FYE should look like and what its goals should be. Spoiler—we were looking for engagement with primary sources through research experiences. We shared the conviction that undergraduate research was fundamental to our curriculum, in our skills classes, content courses, and senior research seminars. Our department even hosts an undergraduate research journal, Virginia Tech Undergraduate Historical Review. We wanted our students to become practicing historians as early as possible. From the first, we asked them not only to engage in research but also to make their conclusions public—even as freshmen. Rather than producing a traditional paper, they created virtual posters that were displayed in a public exhibit in the campus library.

Last fall, though, we made some changes: in place of individually chosen research, we tried a directed class project. I worked with two archivists, Kira Dietz and Marc Brodsky, to identify a project that would allow students to practice the valuable skill of transcribing documents while contributing to the work of the University Libraries’ Special Collections. Digitized research materials, as novice historians in previous classes had pointed out, seemed distant to them because they were mediated through the internet; somehow they were less real. The archivists had a solution: they identified an untranscribed body of letters, written by a Virginia Tech veteran of World War I, Joseph F. Ware Sr., commandant of the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets in 1911–14. More than 100 handwritten letters, mostly written to his wife, Susie, in Blacksburg, Virginia, in 1917–19, waited to be transcribed, digitized, and analyzed. Special Collections staff offered us their time and expertise throughout the semester.

Unlike most crowdsourced transcription projects, my students worked with physical letters that had to remain in Special Collections.

From the outset, our project differed from those undertaken by “citizen archivists”—amateur and armchair historians. Ultimately aiming to make resources more widely available by creating digital archives, most transcription projects are goal-oriented, and the primary goal is completion. (Afterward, trained historians can analyze them.) But I wanted these FYE students to be transcribers, analyzers, and interpreters of the documents, to train on the job, and to focus on both process and product.

Transcription, therefore, was not just a means to an end but an exercise in careful observation, precise description, occasional deciphering, close reading, and, finally, posing questions about text and context, culture, language, and more. In terms of pedagogy, students would benefit from intense focus and time afforded to observation, allowing for the generation of ideas, analysis, and interpretation.

Unlike most crowdsourced transcription projects, which can be done by anyone with access to the internet, my students worked with physical letters that had to remain in Special Collections. It was immediately clear to them that these texts were material culture as well as one-offs. There existed only one original of each letter, and they were allowed to hold it—with clean hands. Most of them had never seen anything (on paper) that was so old.

The assignment was straightforward: read each letter, make preliminary comments regarding the physical characteristics of the letter, and then transcribe it, following the guidelines from Special Collections. Transcribing was not as easy as the students had expected. Commandant Ware’s penmanship was quite lovely, but the handwriting was old, faint, and cramped at times. Sometimes sentences continued onto the back page or even the facing page. Ware used paper from various hotels as well as notebook paper. The letters were of different sizes, some written in ink and some in pencil, and often phrases or sentences were crossed out. Additionally, Ware named people, places, and events with which the students were not familiar, rendering it harder to make educated guesses. Transcription, as the students learned, was not always neutral.

But a remarkable thing happened. These letters became the students’ letters. In many cases, they were in awe of them and remarked on holding history in their hands. They became attached to the ones they were assigned to transcribe, and they became invested in helping others read tricky passages. In some ways, it was a puzzle—what did each letter say, and what did each letter mean? For a couple of months, these students frequented Special Collections, visiting “their” letters. Apparently, their enthusiasm (and number of visits) surprised the archivists, who praised their attachment to the physical letters themselves. And while we often see transcription as a task to be done before the research begins, our archivists knew the value of observation itself and working with objects. [1] Study of the objects called for context, and so we continued.

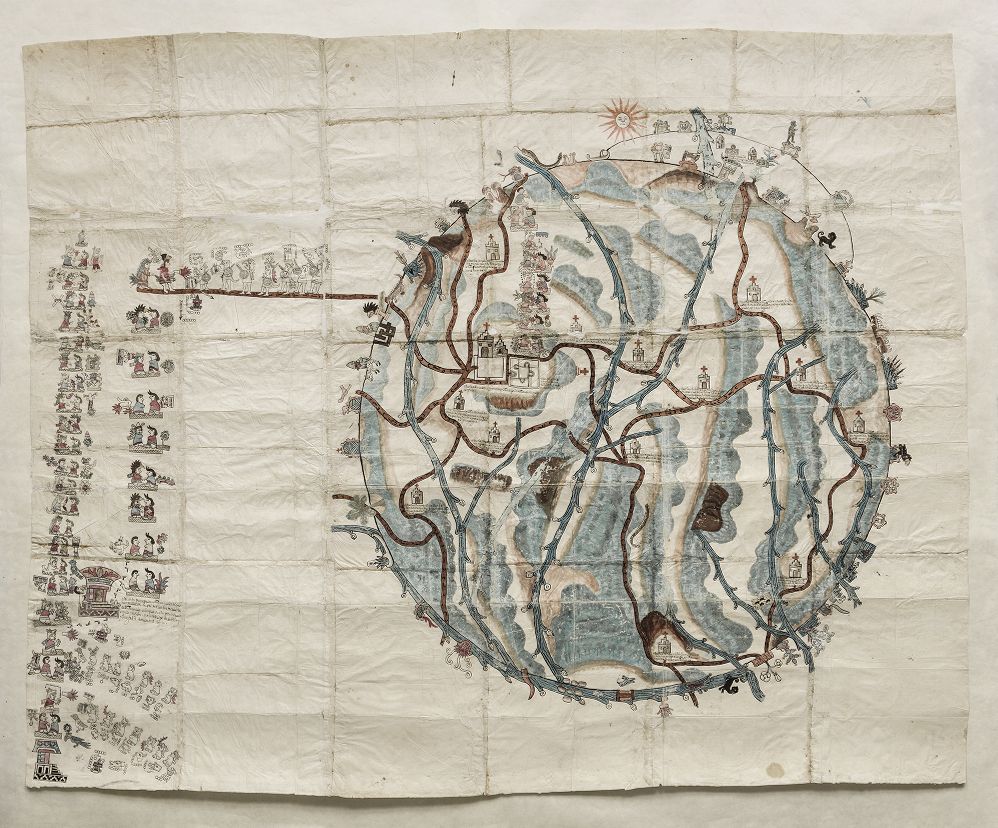

Once the transcriptions were done, students began researching questions they had raised and created thematic posters. We had never intended for the project to be solely transcription; we wanted to tell a story. The move from transcription to analysis was smooth; there was little heel-dragging because these young historians wanted to know what the letters meant. The move into historical research and writing was organic. Students constructed a timeline of events in which Ware was involved, a map showing the provenance of his letters, a collection of his comments on war, commentary on home-life issues, and more. Their reading (and handling) of the documents prompted questions about context, provenance, community, and other related issues. (A digression: Working with the letters also raised questions of conservation and preservation, of the formation of collections, of collection management, of authenticity, of bias and silenced voices—for example, where were Susie’s letters?—which we engaged in with the help of Special Collections.)

These letters became the students’ letters. In many cases, they were in awe of them and remarked on holding history in their hands.

As it turns out, Special Collections’ cache of the letters of Joseph Ware Sr. ends with a letter written well after the bulk of the others. Joseph Ware then disappeared. We had plotted his location from Panama to Plattsburgh, New York, from France to Koblenz, Germany, but the letters dried up. I had already seen the students’ attachment to the story, which now they could not finish. In fact, one day earlier in the semester, I had to show them the divorce certificate of Joseph and his wife, Susie, and I’ll never forget the groans and shock and head-holding that followed. Though we had originally been concerned with Joseph Ware as a project in which to learn skills of transcription and a World War I veteran of Virginia Tech, the students could not let Joseph go because we were going to tell his story.

A email by one student to Joseph’s son’s wife brought tantalizing info—that Joseph Sr. had perhaps remained in Germany after his time in Koblenz, was a spy during World War II, possibly was captured and sent to a camp, and later escaped and married a German woman. Unfortunately, Joseph Jr.’s wife had never known Joseph Sr., who had died in 1969, long before her marriage to his son. Students were unsettled that Joseph was gone. We knew only that he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in 1969. When I found what appeared to be his German wife’s obituary, published in 1993 in an Asbury Park, New Jersey, newspaper, students latched onto it in the hopes of finding more about Joseph Sr. Indeed this Mrs. Ware had been raised in Germany and had moved to the United States around 1945. Perhaps there was truth to the tantalizing story.

Unfortunately, a semester is only 15 weeks long. Our culminating class exhibit, held in Virginia Tech’s Newman Library, attracted faculty, friends of the students, and others interested in World War I. The audience included the archivists from Special Collections, whose observations on the work and drive of the students offered the most satisfying comments an instructor can hear. Our success in capturing the students’ attention had everything to do with the firsthand nature of the materials from Special Collections. I suspect that future FYE classes will look for similarly engaging and focused transcription projects based in our archives.

Note

[1] See, for example, Eleanor Mitchell, Peggy Anne Seiden, and Suzy Taraba, eds., Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning through Special Collections and Archives (Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2012).

Trudy Harrington Becker is senior instructor in the Department of History and Classical Studies Program at Virginia Tech and has been an instructor for its FYE course from its inception, seven years ago.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.