Academic conferences do indispensable work. Yet this work is often rendered invisible by their sheer ubiquity. The COVID-19 pandemic and its disruptions helped bring into sharp relief the many needs in-person spaces of intellectual sociability served. In 2020–21, surging case numbers caused whole conferences—from small workshops to sprawling international events, including the AHA’s 2021 annual meeting—to shut down.

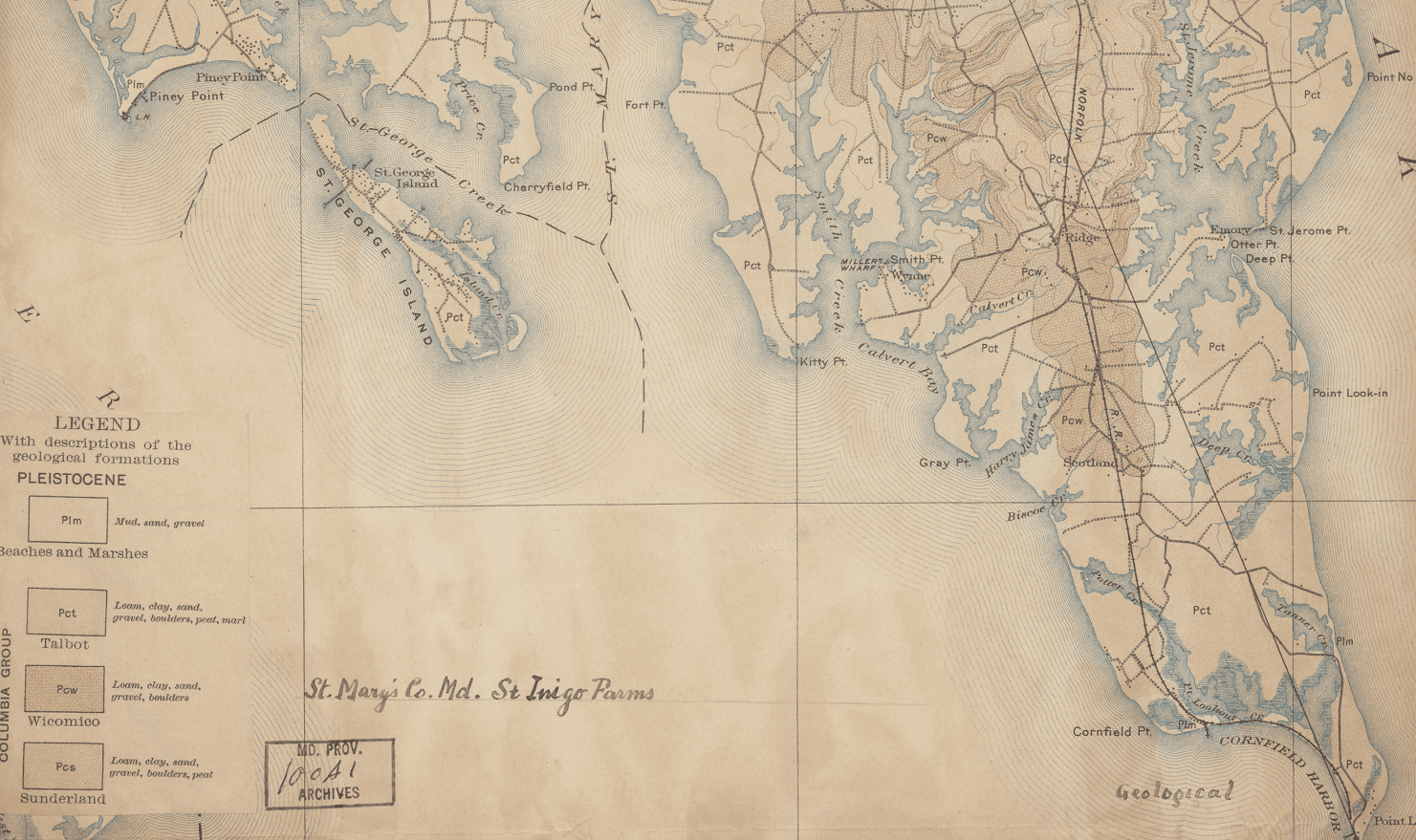

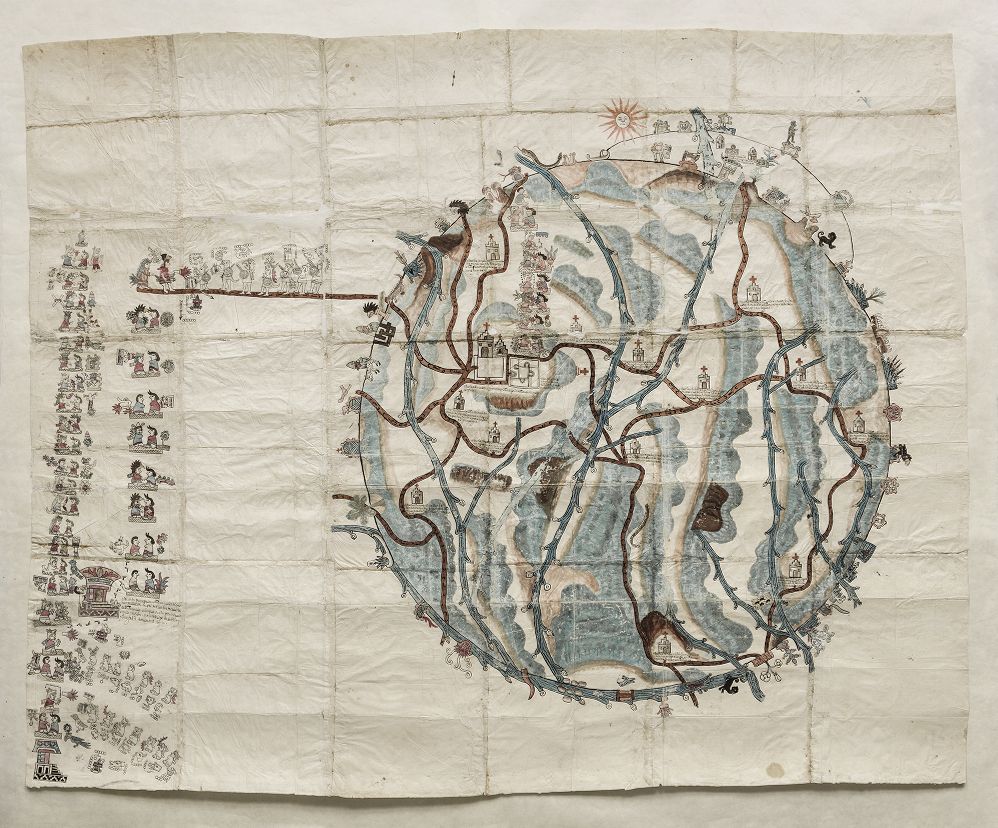

With the 2022 Lozano Long Conference, Latin Americanists were able to connect across the globe via presentations, discussions, and articles. LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, University of Texas at Austin/public domain

After a short pause, many such events moved online. Intended as a temporary fix, these events modeled themselves on prepandemic conferences, with the goal of permitting academic discussion to continue until researchers could resume “normal” in-person meetings. The results were mixed at best. Online accessibility meant attendance soared, especially at international conferences. And yet a common (and fair) critique was the lack of opportunities for connection, extended dialogue, or informal chats. The loss was felt most acutely by graduate students, who found themselves marooned on the edges of many online conferences with few, if any, chances to network effectively with senior scholars.

This was the backdrop that informed our experiment with the Lozano Long Conference, held online in spring 2022 by the University of Texas at Austin in celebration of the Nettie Lee Benson Library and Collections’ centennial. Focused on “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives,” this fully online event was an opportunity to reimagine parts of the conference model. Teresa Lozano Long’s generous endowment to the Institute of Latin American Studies in 2000 helps fund this annual event, and her passing in March 2021 made it especially poignant. In her honor, we sought to expand knowledge about Latin America with a new conference format that would better address entrenched obstacles to accessibility, open new routes for participation and engagement, and expand networking opportunities for all participants, especially graduate students.

The result was something more than a standard academic gathering. We call it the “long conference” in part to honor Teresa Lozano Long but also because the event experimented with standard conferencing timelines. By incorporating an extended prelude, a publication series, and a permanent online presence, we sought to address the major weaknesses of the online conference format in particular and the academic conference in general.

First, we worked to build momentum by creating networking and publication opportunities for graduate students in the lead-up to the event. Second, we flipped the conference format, creating more room for bilingual discussion by requiring prerecorded presentations. And third, precisely because the conference focused on archival questions, we sought to turn the conference into an enduring academic resource by hosting all the videos online. In the end, the long conference opened intellectual exchanges that allowed participating graduate students (roughly 30 in total) to gain significant professionalization and networking opportunities, while also connecting academics at universities located around the world.

We began planning for the February 2022 conference in January 2021. This was an especially uncertain moment in the rolling crisis that was the pandemic. Although vaccines were available, access was significantly restricted. Homeschooling young children and caring for the sick imposed additional restrictions on mobility. Cross-border travel was difficult at best as the pandemic rendered the already time-consuming process of fulfilling visa requirements slower or sometimes simply impossible.

We sought to expand knowledge about Latin America with a new conference format.

Faced with this environment, we opted for an entirely online conference. In addition to the obvious public health benefits, switching to Zoom (the platform most participants were familiar with) came with several clear advantages, especially for a conference focused on Latin America. While in-person conferences can be extraordinarily cosmopolitan and productive, these events rest on some hard economic realities. Attendees tend to come from a small subset of elite academics who enjoy financial support from their home institutions and are fully comfortable in English. Graduate students, early career scholars, and scholars at underfunded institutions who are unable to afford the costs of travel, accommodation, and registration fees are too often marginalized from precisely the opportunities that only international conferences can provide. Scholars from developing countries face additional constraints. While academics from rich countries can travel around the world without applying for a single visa, their counterparts from low- and middle-income countries are required to obtain them, which necessitate a time-consuming, expensive, and sometimes humiliating application process. The environmental impact of long international flights adds yet another layer of concern.

By contrast, the online format allowed us to invite a diverse list of participants. They included prominent scholars like Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo (Univ. of Chicago) and Miruna Achim (Univ. Autónoma Metropolitana Cuajimalpa); public intellectuals like author Cristina Rivera Garza, and Adriana Pacheco, the founder and producer of Hablemos Escritoras podcast; and community archivists and activists such as Inez Stampa and Vicente Arruda Câmara Rodrigues from the Centro Memórias Reveladas in Brazil, and María Paz Vergara from the Fundación de Documentación y Archivo de la Vicaría de la Solidaridad in Chile. In a postevent survey, one speaker noted that an online event of this nature “is the only feasible way to have a robust and varied participation of scholars, archivists, and activists from the whole of Latin America.”

While going online solved some problems, it created others. As we planned the event, several of us had firsthand experience of the most common critique leveled against online conferences: the lack of genuine opportunities for substantive engagement outside of formal presentations, especially for graduate students. We therefore deliberately created spaces for interaction between graduate students and the scholars, archivists, and activists we planned to invite.

As our starting point, we identified three graduate students (co-authors on this piece) whose research interests resonated with the conference’s archival theme. We formed a special directed readings course where they collaborated with the faculty organizers to identify, read, and analyze significant scholarship that addressed the archival turn in the humanities, with a focus on Latin America.

Outside this core group, we identified a wider cohort of UT Austin graduate students whose research interests intersected with the specialties of conference presenters. We invited these students to interview and write extended profiles of conference participants. Because we were no longer paying for international travel, we redirected funds to pay honoraria to graduate student writers for 25 profiles. The result was a series of fascinating and illuminating pieces published by the digital magazine Not Even Past, including “Knowledge and Power Are Not the Same,” “Archives and Their Afterlives,” and “Archiving the Brazilian Dictatorship.” By pairing student writers with presenters based on shared interests and expertise, we ensured that dozens of our graduate students had a clear path toward building out their professional networks.

Beyond the benefits to graduate students, these profiles served to contextualize the work of the scholars and activists presenting at the conference. In traditional conferences, brief introductions rarely do justice to presenters’ work. These articles went deeper, identifying career trajectories, the significance of published work, and the impact archivists and activists had on their communities. As Camila Ordorica noted in her piece on Miruna Achim, “Through our conversations I have found that talking with the authors of the books we like and the ideas we respect humanizes and demystifies both the research process and the researcher.” In the postevent survey, participants praised these profiles as both “one of the most interesting aspects of the conference” and “a great way for students to have that networking opportunity.” By publishing them in the weeks leading up to the conference, we succeeded at the same time in generating momentum for the event.

During the live stream of each panel, bilingual graduate students translated conversations in Spanish and English.

On February 24, 2022, the Lozano Long Conference went live for two consecutive days, with speakers zooming in from Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Mexico, Russia, and across the United States. Without the cost of travel, hotels, and per diems, we could offer participants honoraria for their work. In exchange, participants agreed to precirculate not just their written presentations but also video recordings of their talks.

By asking them to prerecord their presentations, we ensured that presenters could discuss complex ideas in the language they preferred, thereby helping to tear down language barriers. Panelists submitted their prerecorded video presentations a few weeks earlier, which allowed for translation and subtitles for greater accessibility. All conference participants and the viewing public could view the prerecorded presentations prior to the live-streamed panels. Audience members who preregistered (at no charge) could watch the prerecorded panels up to two weeks in advance of the conference, and they could submit questions to the conference organizers on the days of the panel.

The precirculation of presentations and conference papers enabled us to open more space for discussion among the discussants, panelists, and the audience. As the conference proceeded, online conference tools also helped reduce some of the standard problems associated with a multilingual event. During the live stream of each panel, bilingual graduate students translated conversations in Spanish and English via the chat function. Live-streamed panels and keynotes were recorded and subsequently transcribed and translated, a strategy praised by our presenters.

What we accomplished through the published profiles, precirculated materials, and language accessibility quickly became clear during conference proceedings. Rather than starting from scratch, we had already created a community where graduate students, senior academics, archivists, and activists were all able to participate effectively.

A website transformed the 2022 Lozano Long Conference into an enduring online resource.

Conferences often feature remarkable presentations, but the traditional in-person format can make them strikingly ephemeral. Once the conference ends, it largely disappears as a scholarly resource for anyone beyond those participants who were present. While some conferences become edited volumes, they seldom capture the excitement of the original discussion. To address this problem, we created a website to transform the 2022 Lozano Long Conference into an enduring online resource. It includes recordings of presentations, panels, and keynotes, as well as the 25 interviews and related articles. Surveyed participants noted that they “consider this aspect fundamental. The memory of conferences must be adequately preserved and disseminated.”

The academic conference is a strange creature. It is an immensely powerful tool for sharing preliminary work, keeping up with scholarship in related fields, forging collaborations, and establishing and maintaining relationships with scholars at different stages in their careers. As such, conferences have been a standard fixture of academic life for decades. Thousands of academic conferences and workshops are convened each year, at enormous cost in terms of time and money. And yet, despite its centrality to processes of scholarly production, the traditional in-person conference format itself has generated comparatively little reflection.

As the pandemic era recedes, the return of the in-person conference is decidedly welcome. But we should also recognize that online conferences can significantly enhance academic exchange by making scholarly meetings more accessible and equitable. Innovations such as our long conference experiment represent one path forward for turning conferences into an engine for broader engagement and graduate student professionalization while also creating enduring resources and access to knowledge.

Lina Del Castillo is an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Adam Clulow is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Camila Ordorica is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin. Rafael Nieto Bello is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin. Janette Núñez graduated from the dual MA program in Latin American studies and information science at the University of Texas at Austin and is now Latin American and Caribbean studies librarian at Michigan State University. Gabrielle Esparza is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.