The Denver omelet is a near ubiquitous offering on diner and greasy spoon menus across the country, but what is the home city’s spin on this American perennial? And what can the culinary history of this dish tell us about the social history of the frontier West? Why not take advantage of a few days in Denver for the 2017 AHA annual meeting to explore these questions?

Denver omelet at Sams No. 3 diner. Credit: Rick Halpern

First stop was Sam’s No. 3 diner, just a stone’s throw from the Convention Center, where the Denver omelet has been on the menu since it opened its doors in 1927. According to our server, the classic version of the omelet has green pepper and onion in it, with the usual addition of cheese. A variant, at Sam’s and elsewhere, adds chopped tomato and rechristens the plate a western omelet. Both, I was told, are traditionally served with hash browns.

Opinion on the cheese component of both omelets is fairly one sided. “If it doesn’t have cheese I’m not even talking to you,” said one long-time Denver resident (and Civil War historian), Frank Deserino. Others queried had equally stringent views about both the type of cheese to be included—cheddar or Monterey jack received the most enthusiastic endorsements—and whether it is best incorporated into the filling or laid on top (and, ideally, run briefly under the broiler).

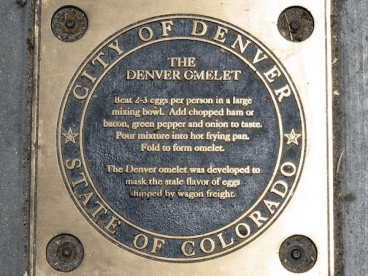

The actual history of the omelet is less clear. Folkore has it that in order to mask the foul taste of eggs on the verge of going off, pioneers on the overland trail would add onions and other savoury ingredients and whisk them together for something more akin to a frittata (and indeed, my plate at Sam’s lacked a filling as such and was more of a folded omelet). A variant, still in the realm of folklore, is that eggs shipped from the east by wagon freight arrived in Denver in less than ideal condition, and hence the use of aromatics. A plaque on California Street (see photo) repeats this tale and also references the fold-not-filling technique.

A plaque on California Street details the recipe of the Denver Omelet. Credit: Rick Halpern

More reliable—and certainly more interesting—is the idea that Chinese cooks working on the transcontinental railroad began preparing hearty sandwiches for section crews, using eggs enriched with left over vegetables as a filling. Culinary historian Harley Judd Spiller speculates that as far east as St. Louis, Chinese rail cooks hailing from Guangdong Province (Canton) adopted their own egg foo yung to this use, and the Dictionary of American Food & Drink suggests that the western sandwich (and omelet) similarly derived from this kind of migrant contract labor. Spiller further observes that in many working-class neighborhoods in St Louis and environs, this hearty breakfast sandwich is still served, though largely to an African American laboring population.

To pursue the railroad argument a step further we can make an educated guess about the shift in terminology from “western” to “Denver.” When the transcontinental line reached Utah in 1869, the now common egg dish was rechristened in honor of the largest metropolis in the region, Denver City, and elevated from a humble workingman’s sandwich to a plated omelet, consumed sitting down, with cutlery and napkin.

The next gustatory investigation is a no brainer. When in the Mile High City how can a couple of hungry labor historians (if staying until the 10th) not check out the roasted goat cabrito in guajillo-chile sauce at a place called, I kid you not, “Work and Class?” (Larimer at 25th).

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Rick Halpern is a social historian who works on race and labor in a number of contexts. He is the Bissell-Heyd Chair of American Studies at the University of Toronto.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.