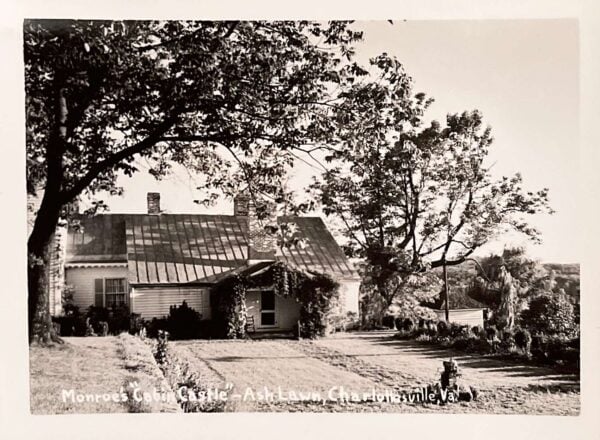

Visitors to James Monroe’s Highland, a historic site located in Charlottesville, Virginia, often ask me if the house is haunted. Highland is haunted, but not as the public imagines it. Instead of a spectral figure that wanders the grounds, the property is haunted by a lost building, known for decades by a different name. In one photograph from the 1940s, a small cottage is captioned as “Monroe’s ‘Cabin Castle’—Ash Lawn, Charlottesville, Va.” This building does date to the Monroe era, but it was never his home, and he never called his home “Ash Lawn.”

“Monroe Exterior/Gardens,” ca. 1940, Highland Collections.

At Highland, Ash Lawn’s traces are deeply embedded in the collection materials. One handwritten ghost story hangs near my office, titled “The Ghost of Ash Lawn”:

’Tis said that when the twilight falls,

And birds have gone to nest

There hovers at Ash Lawn

A gentle spirit of unrest.

And through the hall, in breathless haste

An eerie presence moves,

There gently rocks, a chair, or crib,

As though a child to soothe

Melodramatic and vague, this poem could be set at nearby Monticello or Montpelier. However, there are specific site connections. The final line might evoke Monroe’s son, James Spence, who died tragically as a toddler, but I do not read this poem as meditation on child loss. For me, the title tells all. It’s not “The Ghost at Ash Lawn.” It is “The Ghost of Ash Lawn.”

Here in central Virginia, the ghost of Ash Lawn is a mighty specter. In 2016, “Ash Lawn–Highland” was renamed “Highland” to reflect what the site’s most notable occupant, James Monroe, called his house during its first decades on the built environment. Despite deliberate efforts by staff, visitors still stand in our exhibit spaces and exclaim, “Oh, is this Ash Lawn?” What further mystifies some visitors is the fact that Monroe’s 1799 home is not one of the buildings they see today. Monroe’s home burned down in the first half of the 19th century, but the remaining and later structures were interpreted as the presidential home. Visitors may have previously toured small rooms displayed as Monroe’s dining room, office, and bedchamber. Now, the site’s public interpretation centers a house without much physical presence. Visitors must imagine the Monroe residence, its foundations outlined by flagstone. Yet they still see the building called Ash Lawn in the extant farmhouse and in surviving tourist materials. While the absence of the 1799 house provides space to tell more expansive histories about the enslaved individuals who may have spent more time at Highland than Monroe ever did, the new interpretation can also confuse visitors with earlier memories of the site.

I do not fear visitor inquiry into ghost stories about Highland. A site’s lore can help us understand how visitors process the multiple iterations and institutional histories of a historic site. Ash Lawn’s lingering shows how people remember old places, like the multiple houses at Highland. Public historians and museum professionals often have little power over such strong public memory. But can we work with it? How do we encourage visitors to interrogate ghostliness as a charged metaphor, especially when there are very real histories of enslavement, trauma, and violence haunting plantation spaces? Though ghosts can be dangerous entities that trivialize and obfuscate, they can provide accessible language to explore who and what remains—like the name of a house.

Mariaelena DiBenigno is the Mellon Postdoctoral Research Fellow at James Monroe’s Highland. She tweets @mxdibe.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.