My grandmother was a painter. Tall and elegant and self-possessed, she wore a silk scarf around her neck like Grace Kelly and smelled of turpentine and strong soap. Her work was far from avant-garde: she mainly painted nostalgic scenes from her childhood in a poor corner of South Carolina. To me she was a figure of glamour, independence, and creativity. As a child, there was nowhere I liked more than her studio, the bright room where she staged still lifes of flowers and figurines, where she kept color-smeared easels and tackle boxes of paint tubes.

Courtesy of Science History Institute

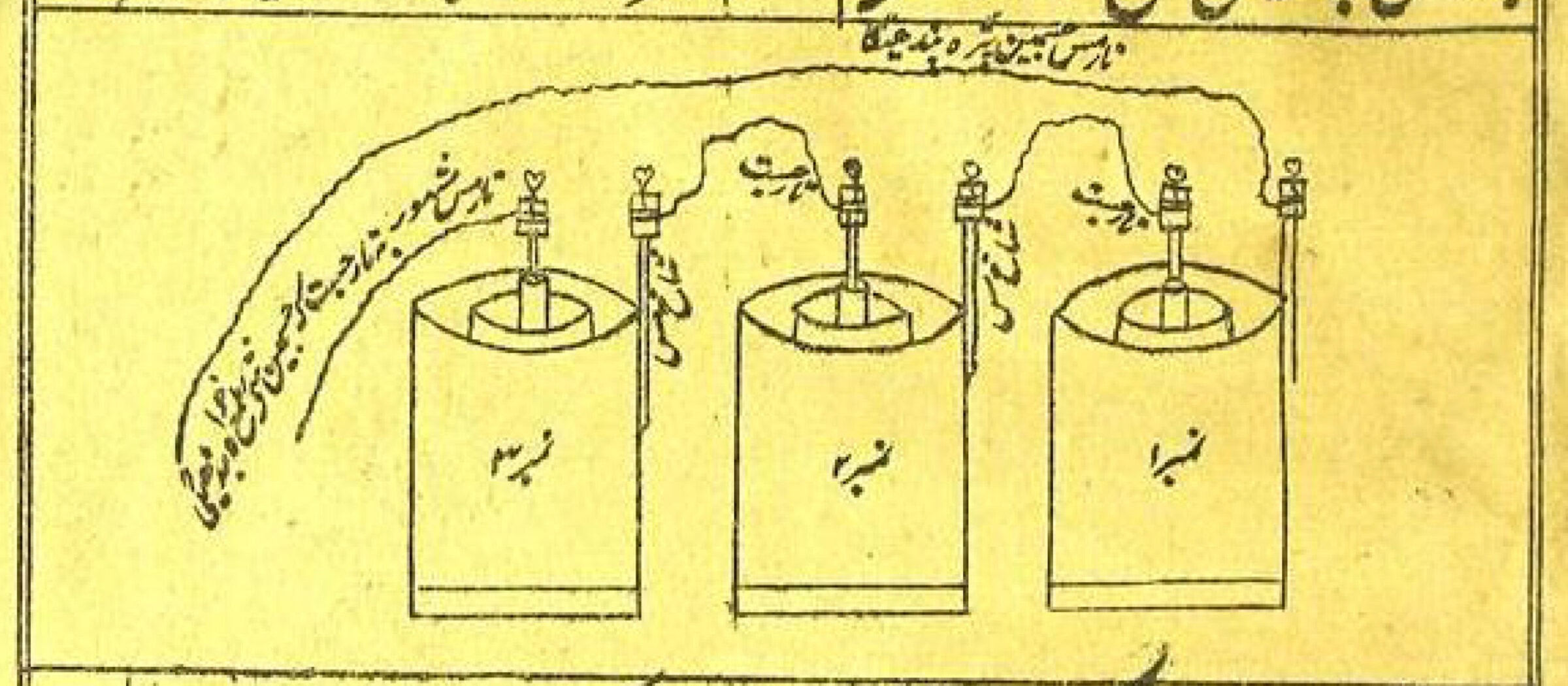

When I first came across this small set of porcelain pigments at the Science History Institute, I felt that same childhood delight at the riotous colors and the orderliness of the case. I am fascinated by the how of art, the messy bits of making behind any finished work. But beyond its materiality, this set contains a fascinating—and gendered—history of engagement with the arts.

Women have historically struggled to gain acceptance and recognition as artists. In the 18th century, French painter and critic Charles-Paul Landon argued that studying to paint from nature (and the nude) would “infallibly tarnish” the “delicate, modest, and peaceful sex.” While the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts began accepting women to certain classes in 1844, it took another 50 years for it to welcome its first woman instructor, virtuosic portraitist Cecilia Beaux. The present-day art world is only marginally more accepting: women constitute only 13.7 percent of the living artists currently represented by European and North American galleries.

Certain modes of art were more acceptable for women than others. Porcelain painting was among them: as a “decorative” art, it married aesthetics to domesticity. An American obsession with porcelain painting was ignited by displays of imported porcelain at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Eager hobbyists purchased “blanks,” or unpatterned pieces, and painted them at home using sets like this one. Highly skilled women could find work at porcelain factories; certain art schools, including the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, even began offering porcelain painting courses. (This set may have in fact belonged to a professional, since the labels have numbers rather than names—porcelain factories used paint-by-number designs to ensure consistency.)

Porcelain pigments are unlike those used in traditional oil painting. The metallic oxides that provide color are mixed with finely powdered silica. When painted on unfinished porcelain and fired in the kiln, they act as a type of flux, bonding permanently to the surface. Highly opaque and viscous, porcelain paint is used in tiny amounts—meaning a set like this could last quite a while. The bright colors were ideal for scenes of flowers and birds, but skilled painters could try any subject: even the famed Cecilia Beaux produced portraits on serving plates.

Despite its respectability, porcelain painting’s popularity with women still exposed it to satire. The painter Earl Shinn (aka the art critic Edward Strahan) complained that porcelain mania led “the loveliest and purest maidens in the land to smell of turpentine.” As a painter’s granddaughter, I can confirm that the smell is potent and astringent. But to me, it’s the smell of discovery and possibility, even freedom. I can only wonder if the person who once owned this set—the woman, even—may have felt the same way.

Elisabeth Berry Drago is a research curator at the Science History Institute and co-host of the Distillations podcast. She tweets at @EBDrago.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.