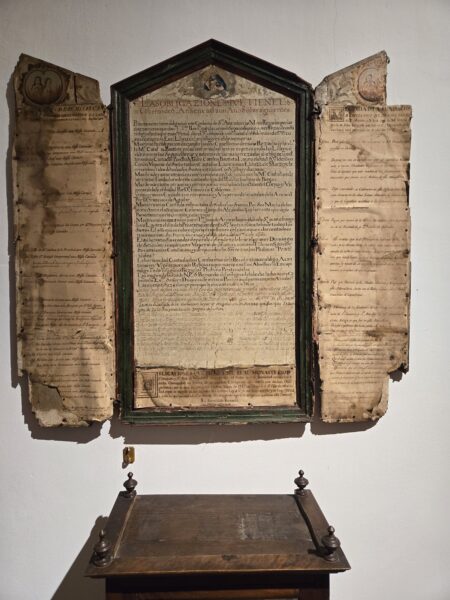

Part wall calendar, part database, this early modern painted wood convent tabla was meant to be hung on a wall—as it is now in the small museum at the convent of San Joaquín and Santa Ana in Valladolid, Spain. There is no label describing it, and the viewer is left to discern its meaning. Close examination reveals it to be a repository of the sacred obligations of the convent. Its use and display allowed the nuns to assert their fundamental role in the city’s spiritual life.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt

The center panel’s text is an early 18th-century accounting of the masses that the convent’s nuns were required to observe for donors each year. As an act of memorialization and to ensure the peace of dead souls, it was customary for the Catholic faithful to commission masses. The chosen institution received an endowment to fund these observances, which were performed by a priest within its church. Additional clues to the tabla’s meaning come from the composite of both printed and handwritten (in several different hands) sheets of paper, affixed to the three boards with nails. The papers on the side panels appear especially worn—perhaps because they would have suffered the most wear and tear as the triptych folded open and closed. The ability to both attach and remove these papers, though, suggests the possibility of updating the information—a kind of bulletin board. Thus, the contents of the tabla were provisional; at the same time, they speak to the enduring obligations and spiritual identity of the convent.

Early modern European society routinely entrusted convents with prayers and masses, and this tabla would have been an important memory device to help meet these obligations. For nuns, who were denied sacramental or other more active service roles outside the convent, these responsibilities held a particular sacred significance and allowed them to forge relationships with local patrons. The bequests that secured these masses would have begun transactionally. Behind each name and mass listed on the tabla was a deeper paper trail, a will or contract prepared by a notary. Convent archives collected such documents (some are even referenced by number on the tabla), but the tabla provided a succinct accounting of actionable items—in this case, requests for masses. The most essential information was pulled from the bequests, listed on a sheet of paper, and attached to the tabla. Masses often transcended generations, with many requested for perpetuity. Nuns present at the original declaration of the bequest would not be there decades later. New requests were always coming in—thus the need to update and replace the sheets of paper. In all these ways, the tabla was a valuable and adaptable reminder.

One could imagine, though, the use of an alternative, smaller memory device. A small book that could be consulted, for example (and we know that nuns kept informal account books and other tallies like this). This tabla, however, is large—at least three feet tall—with painted illustrations atop each panel. The penmanship is neat and careful. It was meant for display. It was likely hung in a semiprivate space like the sacristy, a reminder of devotional obligations to both the nuns and the priests who performed the masses. Nuns, as women, could not wield this sacramental power. But were the tabla only meant as a memory device, it would not require this kind of presentation. The tabla was not just a tally; it served another purpose.

Despite not being able to perform the masses themselves, with the tabla, the nuns could visibly assert their part in this sacred responsibility. Donors could endow masses at any number of religious institutions. Valladolid was replete with churches, monasteries, and even other convents. But the donors listed on the tabla chose this convent as the place that would protect their souls and legacies and those of their beloved relatives. The tabla serves as a declaration that transcends the ecclesiastical limitations placed on nuns. Its creation and display materially attest to the nuns’ enduring roles as vital participants in the spiritual economy of the community.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is professor of history at Cleveland State University and was vice president of the AHA’s Teaching Division in 2016–19.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.