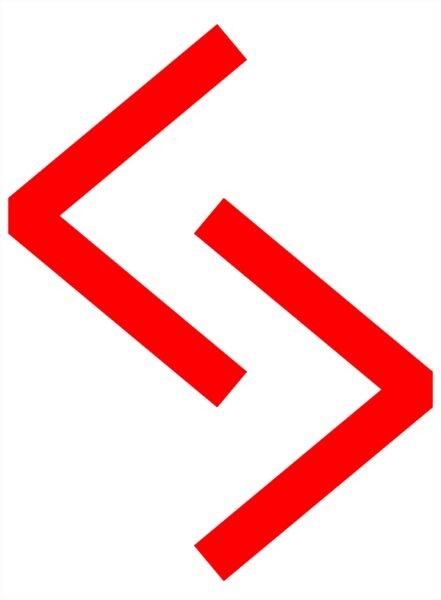

The jera rune

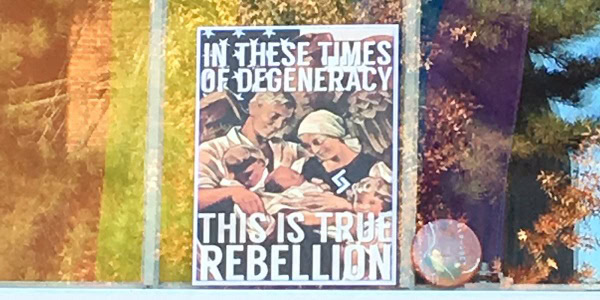

One week after the November 2016 election, white nationalist posters were hung on several buildings at Iowa State University in Ames (fig. 1). It was the second time that semester that such posters had appeared in the middle of the night on the campus where I teach history.

Iowa State is not alone. The Anti-Defamation League documented 159 incidents of racist fliers and stickers placed on 110 American college campuses in the 2016–17 academic year alone.

As they did the first time, university administrators removed the posters quickly and issued a brief press release and statement to the campus community. But as a white historian teaching at a majority white institution who researches the production and transmission of racial ideas in Germany, and as a teacher of modern German history, I could not hope the whole issue would go away, as our administration seemed to do.

I did not believe I would persuade these poster-hangers to cease their surreptitious business. Instead, I wanted to disrupt their deceptive identitarian message. I decided to set aside my lesson plan for the next day’s class and discuss the posters and their direct connection to the iconography and ideology of National Socialism.

Fig. 1. This white nationalist poster appeared on the Iowa State campus in November 2016.

Iowa State’s student population is drawn largely from the rural and suburban population of Iowa and its neighboring states, and is overwhelmingly white: 87.3 percent of the student body in fall 2016. This informed my strategy about teaching this controversy. I could not lecture to my students or alienate them for being who they were. Rather, I would present the evidence to them and allow them to draw their own conclusions.

Knowing my class was key. There is certainly on campus—and perhaps among the students of my class—a very small minority of students who basically agree with white nationalist messages. A second group, larger than the first but still a minority, comprises liberal or progressive students hungry to have their professor reinforce their worldview. But the overwhelming majority of my students range from moderately conservative to moderately progressive. These students may possess a theoretical commitment to inclusivity and multiculturalism, but they have little personal experience in applying it.

I did not believe I would persuade these poster-hangers to cease their business. Instead, I wanted to disrupt their deceptive message.

So I focused my lesson on this latter group. Instead of telling them up front what the poster advocated, I planned to highlight three of its elements: the image, the slogan, and the symbol on the woman’s dress. My aim was to help my students recognize the posters for what they were: repurposed Nazi iconography mixed with white nationalist ideology. This lesson, I hoped, would frustrate the attempt by the poster’s creators to conceal their violent hatred in a seemingly reasonable and moderate narrative.

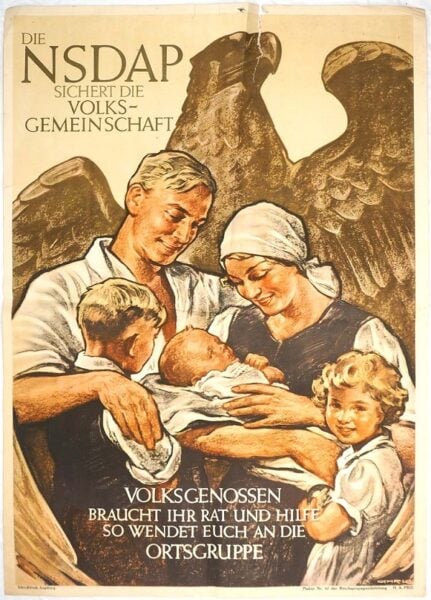

I started by showing the original image—a 1935 National Socialist Party poster (fig. 2)—alongside the poster hung on campus, and asked the class if they saw anything familiar in the former. Students immediately connected it to another image I had shown when we discussed the Nazi policy of “positive eugenics.” It was an undated print taken from a painting by the SS- and Nazi-funded artist Wolfgang Willrich called The Aryan Family, which I found online (fig. 3).

The students themselves generated incisive commentary: the emphasis on a narrowly defined “traditional” family structure depicting a protective father and nurturing mother, with an older child bearing witness to his or her parents’ careful performance of parental duties.

They also grappled with the poster’s slogan: “In These Times of Degeneracy This Is True Rebellion.” When I asked what “this” referred to, they identified it as the healthy (white) family. Several students puzzled over “this” as rebellion, as well as what the “degeneracy” could be. As they pointed out, a political act of rebellion brings with it an implicit threat of violence. The use of the family group in both posters made it clear that the creators meant to include and exclude specific people from their notion of community. The celebration of the “traditional” white family, students said, indicated hostility toward those who would not or could not emulate the image on the poster.

In considering “degeneracy,” my students expressed dismay at the rhetorical violence of the poster toward those in multi-ethnic, multi-racial, and same-sex relationships. Several empathized with members of the university who might see one of these posters and feel threatened or unwelcome because of its message.

Fig. 2. A 1935 National Socialist Party poster. The German words speak of “the People’s Community.” Collectors Guild (germanmilitaria.com)

Preparing to talk about the third element in the poster—the esoteric symbol on the woman’s dress—required some sleuthing into the alt-right and white nationalist corners of the Internet. At this point, professional networks showed their worth; a fellow historian at another institution replied to my online queries and located information in two places about the symbol.

The symbol is a rune from an ancient Germanic alphabet, representing “j” and commonly known as “jera.” Though it is often connected with the harvest, neo-Nazis, alt-righters, and white nationalists of the Internet also use it to signify their anticipation of a white or Aryan renaissance.

This research allowed me to explain to my students that this white nationalist theory of a future renaissance had a corresponding theory of current decline: a belief that the political, social, and demographic situation in the United States today constitutes a “white genocide.” Immigration, integration, miscegenation, abortion, and low fertility rates among people of European descent are supposedly promoted in historically white-majority countries as part of a deliberate plan to cause the extinction of the white race. This theory also encompasses homosexuality and legal punishments for hate crimes; a “Zionist Occupation Government” controls the United States and other majority-white countries, with Jews, Jewish influence, and political liberalism all behind this program.

My students quickly cited the jera rune as evidence of an “inside joke” made by the poster’s creators. They noted that many viewers might see the poster as strong but relatively harmless conservative messaging. But by including the rune, the makers of the poster communicated with those in the know. One student observed, “The poster sends this message that most people will see and just kind of move past, but if you’re someone who recognizes [the jera rune], you’ll know that you’re not alone.” Another told the class that the rune might “get someone to go looking for that symbol to find out what it’s about.”

My students noted that many viewers might see the poster as strong but relatively harmless conservative messaging.

What to do about the posters on our campus excited debate. Some students felt it right that the university had removed the posters. Yet a majority felt scandalized that they had not known much about the event. They also argued that the quick and quiet removal from campus allowed the creators of posters to have the last word and “dominate” the conversation. We even mused about a situation in which we left the posters up but hung our own posters (or placed experts on campus nearby) to rebut and refute the message.

One student said, “I wish there was a way to have a discussion like we had with everyone who sees the posters.” It’s a sentiment that goes to the heart of the question of how we respond in public spaces where white nationalists peddle their message with increasing confidence.

Fig. 3. The Aryan Family (undated). bpk Bildagentur/Art Resource, NY

My answer is that historians have the advantage over white nationalists of knowing about the past in substance and context. Our dual roles as investigators and educators give us a unique set of skills to stand against messages of hate and terror on our campuses. White nationalists offer a version of history constructed from hate-filled first principles, carefully elaborated from historical minutiae and insidiously argued from purposeful distortions. Using the tools of a historian, my students critically engaged with material surrounding them. Together, we contextualized one piece of white nationalist discourse and revealed the hatred embedded within it.

I hope students took the insights they generated into conversations in dorm rooms or at cafeteria tables. But I do not think this lesson plan helped any convinced white nationalists to change their minds. My goal was to help students deconstruct a message that had been crafted to appeal to moderate or conservative white students who might feel their values and status under threat in an increasingly diverse America.

Centering students in this process of analysis should inform efforts to offer an effective classroom response to white nationalism. Students do not need our chastisement or instruction on what is just and what is good. With enough information to evaluate the poster and its message for themselves, my students responded carefully and judiciously.

When we use the tools we possess as historians, many of our students listen, especially when we treat them with a respectful openness to discussion and debate. This is truly something white nationalists are unable to counter.

Jeremy Best is assistant professor of history at Iowa State University. His research focuses on globalization, race, and religion among Protestant missionaries and their supporters in 19th-century Germany.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.