The Quilt Index has received major grants from the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the National Endowment for the Humanities and in-kind support from Michigan State University for the research and initial development phases. Additional grant support for expanding content and developing user tools has been provided by a number of private and public contributors.

Digital archives of thematic material culture collections are much more than gatherings of data; they are resources that allow historians to ask different kinds of questions about events, people, objects, and texts. For example, “What can the patterns of 18th- and 19th-century quilts tell us about British imperialism and the global textile trade?” In the past, this question would have been difficult to ask, let alone answer. Quilt patterns were dispersed from their points of origin over time and space, their paths of migration difficult to trace because documentation, if available, could not be easily compared and contrasted in terms of geographic location and or date. With the advent of the Quilt Index, an individual can now search and compare quilt-related data and begin to answer that question, and many more of equal complexity.

Quilts are an important aspect of material culture history that record and reflect particular times, places, cultures, and individual and collective experiences, and the Quilt Index (QI)—a partnership of the Michigan State University Museum, Matrix: The Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at Michigan State University, and the Quilt Alliance—provides instant and searchable access to over 55,000 digital photographs, texts (oral, video, and written), and documents pertaining to their creation, dissemination, and context. The QI is a free, open access online database, launched in 2003, that allows a variety of scholars to ask bold new questions.

Focused on quilts, quiltmakers, and quilt-related materials, and built by quilt scholars, digital humanists, and museum and archive professionals, the Quilt Index covers material from the 17th century to the present. The QI serves a wide range of research and teaching interests for scholars and educators: from analyses of material culture in literature, to studies by art historians of the development and dissemination of particular patterns or techniques, to explorations by women’s, ethnic, labor, and social historians, from computer scientists interested in pattern recognition to educators interested in teaching with technology.

The QI offers a rich source of primary and secondary material through the stories of the making and use of the quilts, text and images sometimes incorporated physically on the quilts, names and patterns of quilts, and fabrics and techniques used to make quilts. These elements support many lines of investigation, and researchers have used the index to pursue a variety of topics. For example, historians interested in migration and mobility have used geographic distribution of quiltmaking patterns or traditions to document westward migration in the United States and the experiences of African Americans and American Indians.

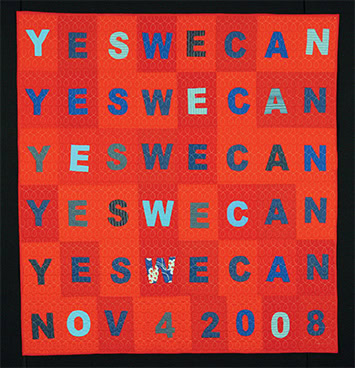

Yes We Can, by Denyse Schmidt, 2008, collection of the Michigan State University Museum.

Historians investigating popular politics will be interested in quilt patterns or title names such as Whig Rose, Whig’s Defeat, President Polk in the White House, Roosevelt Rose, and Yes We Can. These entries and the QI’s collections of pieces of printed fabric featuring images of candidates incorporated into tops, or political ribbons sewn into crazy quilts, can document political sentiments and can be cross-referenced regionally or mapped.

Quilts created for children, including doll quilts and nursery rhyme quilts, provide research material that can reveal cultural perceptions about and experiences of childhood.

Medical historians have researched quilts affiliated with health and wellbeing, which are important documents of individual and collective experiences of caregivers, health educators, medical practitioners, and those living with illness.

Quilts related to workers’ rights can be invaluable to the labor historian. Some quilts were created as documents of workers’ struggles, such as an arpilleramade in Chile that documents professional workers’ strikes. Other quilts provide insight into living conditions and how workers coped with poverty, such as the crazy quilts made of pieces of new or recycled fabrics from the maker’s workplace.

The histories of organizations are often reflected in quilts made by individuals and groups belonging to or supporting them. Many quilts in the index are related to hundreds of local, national, and international organizations. The index includes quilts made by members of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the Freemasons, and even the Ku Klux Klan, not to mention many, many quilt guilds.

The QI is also an outstanding source for investigation of popular memory. Quilts are often made by individuals and groups to record events and experiences that have special meaning to the makers. The QI includes quilts that mark important family events such as births, marriages, and anniversaries, and commemorate local, national, or world event ssuch as 9/11 or Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

The functionality of the QI allows for teaching as well as research opportunities. As host to both previously inaccessible quilt documentation and museum and library quilt collections, the site provides access to individual objects that can be analyzed or researched further, as well as sets of objects that can be studied for evidence of change or constancy over time.

An early American history class could study a quilted petticoat from Connecticut colony dated 1754 as a source for exploring issues of gender and class through the material evidence and symbolism found in the embroidery. For a US history survey course, a database research assignment might focus on a specific historical period, such as the Civil War or the Depression, or a significant date such as 1945 or 1976. Students could conduct searches and seek patterns in the images, quilt-related stories, and other data that provide evidence for arguments about the effects of historical events on individuals, communities, or home life. Fundraising quilts for various causes feature embroidered names of community members and provide detailed sources listing many individuals by name. Historical analysis of listed individuals from a group or community on a fundraising quilt can augment the student’s project.

Petrol Queue, 2005. From the Harare Patchwork and Quilting Guild in Harare, Zimbabwe, collection of the Michigan State University Museum. Queuing for necessities is commonplace in Zimbabwe; petrol queues like the one shown here may stand still for days.

Although the majority of data in the index is of US origin, an expanding number of quilts from around the world now allows research on comparative traditions, immigration and migration histories, trade history, political histories, and even investigations into histories of human rights causes. Some South African quilts in the index, for example, portray aspects of the struggle against apartheid (cover image), while other South African quilts reflect the textile traditions of their makers of British lineage. A Zimbabwean quilt, depicting a long petrol queue, documents an impact of the current political and economic conditions in that country. Ralliquilts from Pakistan can be compared to similar quilts found in India, thus providing a body of data that can examine the impact, or lack thereof, on traditions specific to cultures in geographic areas where there have been shifts of political borders and disruption due to religious and ethnic conflicts.

Metadata on each quilt in the index may include detailed physical descriptions of the object, information on its maker and place of origin, and stories of the makers and users of the quilts. Robust search features permit keyword searching of all quilt data records, as well as detailed searches within specific collections, time periods, or categories such as pattern title, maker, locations, date, and subject. The index also offers essays and curated galleries that provide thematic context for selected groups of quilts. A growing number of lesson plans hosted on the site provide examples and ideas for incorporating the index into classrooms topics and activities. Current lesson plans on the index feature topics such as Appalachian quilts and culture during the Great Depression, exploring late Victorian aesthetic ideas through quilts, and becoming a “quilt detective” by learning to use quilts as primary source material. Social media tools such as a Quilt Index Wiki have user-generated information on quilt documentation projects and quilt collections. A blog and a Facebook page facilitate community building and knowledge sharing among academic and lay users of the index.

The QI includes data from a growing number of public archives, libraries, and museums as well as collective and personal research projects and private collections. This base is continually growing, with new images being added from existing projects and new collections through a staff-reviewed application process. A public submissions portal that will allow individuals to submit quilts is being developed, as is the capacity for users to contribute new information on each record. Beyond the search and browse functions, new forms of discovery for the online collections featuring visualization tools are being tested that will enhance the possibilities for analysis. The addition of quilt-related ephemera and journals has already broadened the types of resources available, and forthcoming additions of oral histories, photographs of quiltmakers, and special sections devoted to quilt guilds will increase the potential uses of the index for historical research.

Marsha MacDowell is professor and curator, Michigan State University Museum and director, The Quilt Index. Justine Richardson is an independent scholar and research associate, Michigan State University Museum and The Quilt Index. Amanda Grace Sikarskie is adjunct assistant professor, Western Michigan University Department of History and Michigan State University Museum Studies program, and research associate, The Quilt Index. Mary Worrall is curator of cultural heritage, Michigan State University Museum, and associate director, The Quilt Index.