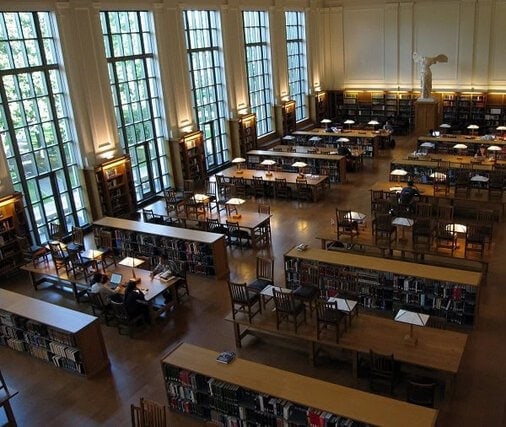

In the digital age, historians can conduct research without visiting physical archives. Nheyob/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

At the 2018 AHA annual meeting, researchers, documentary editors, librarians, archivists, and educators gathered at a series of panels, “Primary Sources and the Historical Profession in the Age of Text Search,” organized by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and AHA staff, to consider how the digital environment is affecting the way historians work. While the digital age has opened up vast research opportunities, it is also reshaping the research process in ways we don’t yet understand.

The digital age has wrought profound changes in the research process, as seen in the massive increase in digitized and born-digital archives that can be explored from anywhere in the world. But discovering materials digitally raises new methodological questions. For instance, researchers should ask why a particular search returned any one result. Additionally, scholars should want to know why a document was digitized in the first place.

Historian Lara Putnam (Univ. of Pittsburgh) isn’t one to mince words about the topic. As she argued in her influential 2016 American Historical Review article “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable,” search engines are flawed research tools: they allow for breadth, but this can come at the expense of context and depth. Historians can use search engines to access relevant sources in an online collection without first gathering contextual information about the document, the collection, or the institution that prepared the collection. Search results tell historians little about the political forces that produced the archive, and they certainly don’t reveal inherent biases that cultural and historical knowledge of a physical institution or archive would.

At the annual meeting, Putnam elaborated on this point. Before the digital age, when archives were primarily place-based, historians would visit buildings to access collections. As they sifted through documents, they gained considerable contextual knowledge about the sources and the institutions that made them available. Now, however, digital searches can be conducted remotely, allowing historians to sidestep the process or avoid it entirely. This complacency—doing digital research without understanding the technologies behind it—is dangerous, Putnam explained: “The historian’s craft is under threat” when scholars “work in a digital environment without interrogating their sources or processes.”

There are good reasons why digital research tools can seem opaque. According to Eileen Clancy (City Univ. of New York), “mediating systems” that deliver information to historians affect historians’ ability to find information. These systems include databases, controlled vocabularies, and search algorithms, and they determine what we find when we do research digitally. Controlled vocabularies, for example, are predetermined sets of words used to describe and organize materials, and they more or less dictate which terms return results when researchers browse a database. Clancy asked, “What happens when controlled vocabulary and other systems impact our ability to find information?” With their result rankings, search engines also have inordinate power, said Ian Milligan (Univ. of Waterloo): “I think I’m writing history, but in reality the search engine is writing history because it’s determining what I click on.”

Databases themselves—created, maintained, and populated by humans—are far from impartial or infallible. Hussein Keshani (Univ. of British Columbia Okanagan Campus), who works with Islamic art, recounted the challenges of researching Awadh visual culture items across several databases. Each database presented different problems resulting from either incomplete controlled vocabularies or inaccurate data. For instance, the database at the British Library included the name of the artist Asaf al-Dawla in the controlled vocabulary for every field except author. Researchers could search for art that had his name in the title or description, but they could not directly look up works by al-Dawla because he wasn’t listed as a creator in the database.

“I think I’m writing history, but in reality the search engine is writing history because it’s determining what I click on.”

Even at the level of individual documents, the digital environment transforms a source. When a physical object becomes a digital object, or even when a digital object is copied or transmitted in some way, changes can occur that are not always apparent to a researcher. A digital image of a primary source will have some relationship to the original, but exactly what characterizes that relationship is far from clear. Putnam pointed out that many historians access a digitized source but cite the physical document in the physical collection, without questioning whether they are really the same. Keshani noted that “the creation of a digital surrogate is a vulnerable moment”—physical features of a source can be changed. He discussed a mirror image of a painting printed in a book; without being familiar with the original, readers would not have known the image was flipped. Historians, he argued, must have the skills to analyze data attached to a digital file, to ask more about the changes it might have undergone.

The alteration of sources is not a new concept or problem for historians. Clancy borrowed book history’s notion of “instability”: any time a text is transmitted from one form to another, changes can happen. When printers used movable type set directly from manuscripts, for example, compositors frequently misread author handwriting and introduced changes to the text. Instability is everywhere in the digital environment, especially as more of our research materials and processes are born digital. Martin Halbert (Univ. of North Carolina at Greensboro) provided a dramatic example of instability: new presidential administrations frequently change governmental websites. Many changes are small, but in some instances entire sites are removed. Certain archival projects—in this case, the End of Term Web Archive—aim to preserve born-digital primary sources like these. Nonetheless, researchers should be aware of this instability.

Historians in this new age need to know about this digitally induced uncertainty and take appropriate action. Alison Langmead (Univ. of Pittsburgh) asserted, “I think we need to train every humanist” how to “sense the digital.” Although we intuitively understand the physical world, she argued, the digital world is much less readily comprehensible, so we must tackle it head-on in our teaching, as early as possible. In the meantime, historians need to start paying more attention to their research processes. “As soon as you start using a search engine,” Milligan advised, “you need to think about what’s going on.” Clancy advised historians to take the time to learn about the databases they are using. She introduced attendees to Beyond Citation, a project that amasses information about scholarly databases for researchers, including details about each database’s history, provenance, and search and browse features, as well as how to access and cite sources from it.

Creators of digital projects small and large also share the responsibility of improving the digital research process. Much of that improvement hinges on transparency. Milligan encouraged everyone to create robust “About” pages for online projects. These might include information about the process of creating the project and collecting the data, the capabilities and limitations of databases and visualizations (if any), credit to collaborators, and unresolved questions. Encouraging even greater levels of transparency, several presenters implored attendees to share their project data and code on GitHub, an online development platform that enables users to collaborate on digital projects. This added step helps preserve the project and enables other researchers to build on the work.

Ultimately, understanding an increasingly digital world is not optional for historians. Jason Rhody (Social Science Research Council) pointed out that algorithms govern much of our communication in the 21st century, and historians need to understand the digital environment in which they live and work. “How do we understand the election of 2016 in the future without understanding Facebook and the way it works?” he asked. If an essential part of being a historian is the ability to look critically at the world, then being a historian in the 21st century requires paying more attention to the digital processes that govern our lives and our research.

Update: This article has been edited to remove a misattributed quotation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.