President Trump’s recent announcement that he intends to impose tariffs on an additional $200 billion in Chinese products is simply the latest indication of his determination to dismantle the international economic order that the United States put in place at the end of World War II. The governing premise of that order was that trade among states should be regulated by rules, reciprocity, and restrictions on protectionist measures. From his rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and threats to withdraw from NAFTA to his attacks on G7 partner nations and placing punitive tariffs on an ever-expanding array of foreign goods, Trump has launched an assault on an economic order that has underwritten America’s global dominance over the past 70-odd years and arguably overseen the greatest burst of wealth production in recorded history.

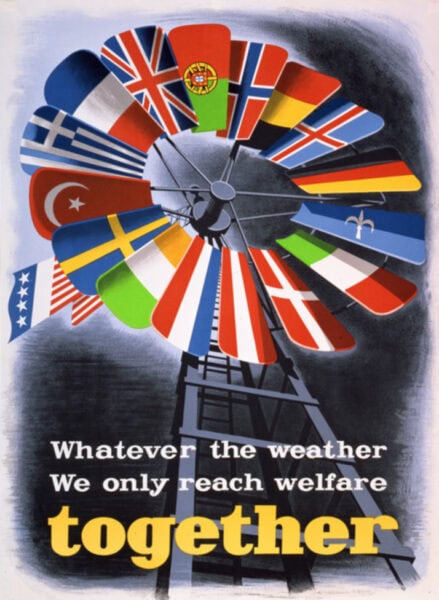

At a recent National History Center congressional briefing, Alfred Eckes argued that the Marshall Plan, promoted in this poster, represented the willingness of the American government to prioritize foreign policy over economic policy. E. Spreckmeester, Economic Cooperation Administration/Wikimedia Commons

The standing room-only crowd that attended the National History Center’s congressional briefing on the history of trade policy late last month reflected the widespread anxiety about these developments and desire to make sense of them. The congressional staffers and interns who packed the room were treated to two starkly different interpretations of America’s history of trade policy and assessments of its implications for the current moment—one of them making a case for the merits of the rules-based system that has governed global trade since 1945, the other arguing that this system has subordinated America’s economic interests to its foreign policy objectives.

Susan Ariel Aaronson, an economic historian at George Washington University and author of numerous books on trade policy, offered a critique of protectionism and defended the international system of trade that Trump has attacked as “unfair” to America. Aaronson acknowledged that “protectionism became the American way” in the 19th century, but argued that its impact was largely negative: protectionism distorted markets, privileged special interests over the public’s interest, and created an unaccountable system of “log-rolling” involving the exchange of political favors.

Aaronson cited the Smoot-Hawley Act (1930), which imposed tariffs on tens of thousands of imported goods at the start of the Great Depression, as an especially egregious case of protectionism. After World War II, the United States reversed course, becoming the driving force behind a new, rules-based system of trade regulated by GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), the World Trade Organization, and other international institutions. While “not perfect,” Aaronson argued that the great virtue of this system is that it has produced trust, transparency, and stability in international trade, managing the demands of different national interests and mitigating the effects of periodic economic crises.

After World War II, the United States became the driving force behind a new, rules-based system of trade.

A contrasting perspective was offered by Alfred Eckes, an emeritus professor of history at Ohio University and member of the US International Trade Commission from 1981 to 1990 (chair during 1982–84). In his written remarks, Eckes characterized the trade policy debate as a struggle between “Wilsonian globalists,” who favor the current rules-based, multilateral system of trade, and “grassroots skeptics” such as himself, who believe that this system has placed an unsustainable financial burden on the United States. The main measures of that burden, Eckes argued, are the national debt, which currently exceeds $21 trillion, and the deficit, which reached $466 billion in 2017.

In Eckes’s estimation, these problems derive from American leaders’ willingness after World War II to subordinate economic policy to foreign policy, starting with the Marshall Plan. As examples, he cited the Eisenhower administration’s decision to promote Japan’s reentry into the international trading community as a Cold War partner without requiring it to dismantle its protectionist policies; the Clinton administration’s decision to admit China to the World Trade Organization and thereby bind it to the international economic order without ensuring that it abided by WTO rules regarding domestic markets and intellectual property rights; and the George H. W. Bush administration’s decision to negotiate a free trade agreement with Mexico (NAFTA) in order to stabilize its financial situation without foreseeing the manufacturing losses that the United States would suffer. Each of these decisions, he argues, subordinated national economic interests to foreign policy considerations.

Neither Aaronson’s nor Eckes’s historical arguments struck me as entirely persuasive. For Aaronson to dismiss as misguided the protectionist policies that the United States maintained for more than a century ignores how those policies nurtured the country’s manufacturing sector, laying the foundations for its postwar global supremacy. Even today, the WTO permits developing countries to maintain higher tariffs to protect their domestic producers. In other words, protectionism possesses a situational economic logic. The question is whether that logic applies to the situation the United States faces today.

Congress has largely ceded its authority, granting President Trump near unfettered control over US trade policy.

And does Eckes’s claim that US officials sacrificed the country’s economic interests to foreign policy considerations stand up to scrutiny? Most historians believe that by bringing European trading partners back to economic health, the Marshall Plan was good for American business as well as American diplomacy. The same synergistic calculations surely informed the decisions US policymakers made in the other cases highlighted by Eckes. To do otherwise would have been political malfeasance. Given the United States’ large, multi-sectorial economy, the real issue is not whether these policies served American economic interests, but rather whose interests they served and whose they neglected.

This brings us to the current crisis. Historically, Congress and the president shared responsibility for shaping US trade policy and determining its beneficiaries. But Congress has largely ceded its authority, granting President Trump near unfettered control over the process. President Trump is choosing winners and losers—thumbs up to steel and aluminum manufacturers, thumbs down to automakers. Moreover, he is doing so in a manner that stands directly at odds with the rules-based system that has regulated international trade since World War II. In contrast to its efforts to establish a fair, transparent, and predictable decision-making process, Trump is acting in an arbitrary, opaque, and utterly unpredictable fashion. With rumors circulating that he wants to withdraw from the WTO itself, we are left to wonder: when will Congress reassert its role in trade policy?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.