Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first installment can be found here.

Striving to reckon with the concentrated wave of violence against Black Americans in the early months of 2020, folk musician Rhiannon Giddens released the song “Build a House” on the 155th anniversary of Juneteenth. Giddens’s keen capacity for storytelling is on full display in this piece, as she expertly narrates 400 years of Black history over the course of four minutes. Solemn, stirring, and hauntingly beautiful, each stanza is a variation on a single theme: Black Americans’ perpetual search for a safe place to call home. The idea of the Black homeplace encompasses more than just a physical barrier from the outside world. It speaks to a place, as bell hooks writes, “where Black [people] can renew their spirits and recover themselves.” Even when faced with extreme opposition, Black families have continued to craft these spaces over the course of centuries. Working in concert, the music and lyrics of “Build a House” reveal this history of stolen lives and stolen labor, of dispossession and displacement, and of resistance and resilience.

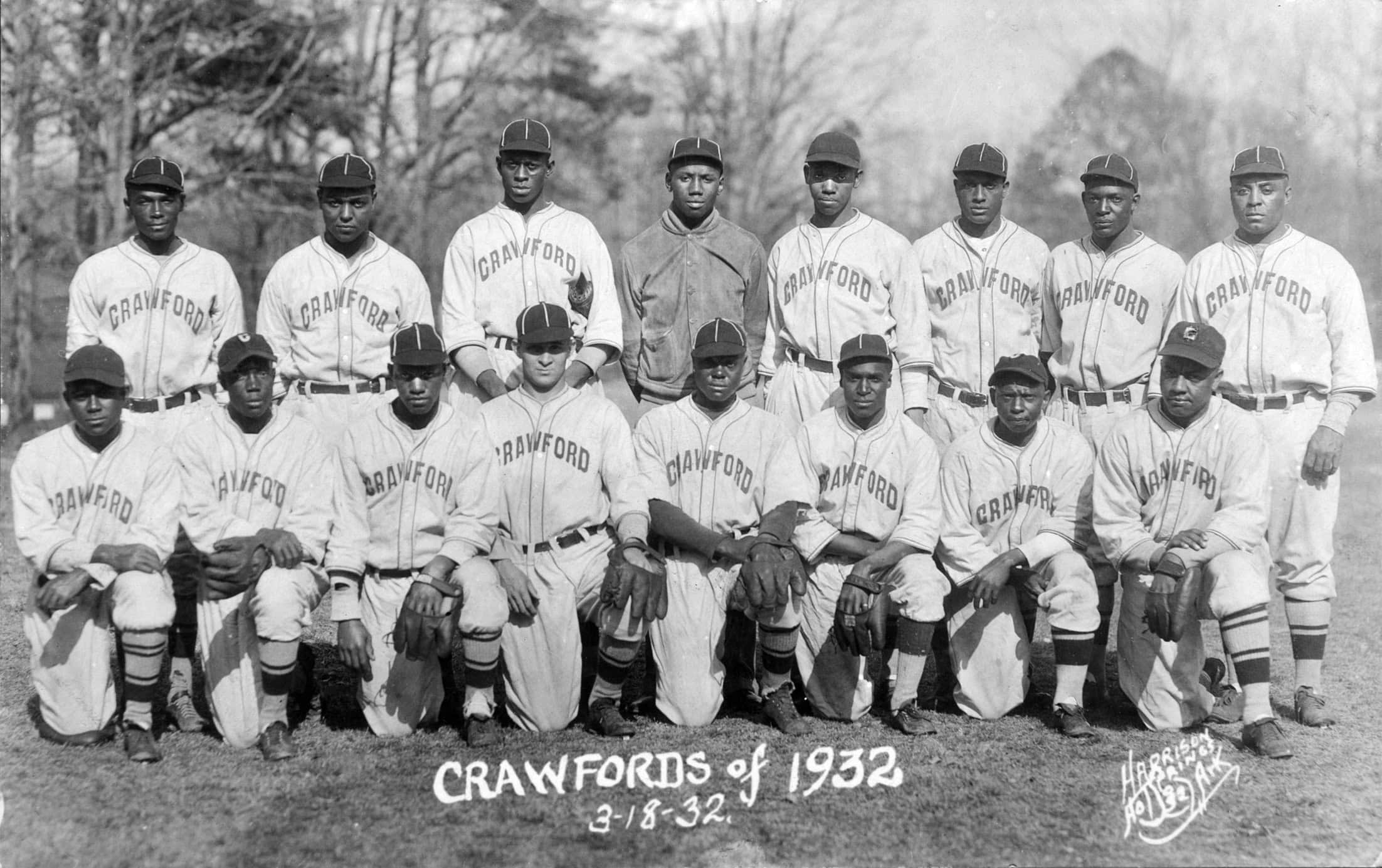

In “Build a House,” Rhiannon Giddens retells a history not just of tribulation but of triumph, not just of persecution but of perseverance.Levi Manchak/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

You brought me here to build your house, build your house, build your house

You brought me here to build your house and grow your garden fine.

I laid the brick and built your house built your house, built your house

I laid the brick and built your house, raised the plants so high.

The opening lyrics of “Build a House” remind the listener that, of the many devastating effects of the transatlantic slave trade, the first was the uprooting of millions of Africans from their homes. In addition to physically removing Africans from the continent, enslavers strove to strip them of cultural markers that tied them to their homeland: their languages, clothing, hairstyles, customs, and religion. But the first enslaved Africans refused to be utterly undone by this dispossession. In the low country of Georgia and the Carolinas, the descendants of enslaved West African people came to be known as the Gullah Geechee. While their rice-growing expertise was exploited to generate enormous wealth for the planter class, these enslaved people took advantage of their large numbers and relative isolation on sea islands to generate languages, religions, and foodways deeply rooted in their African heritage. Even as they were prevented from profiting from their own labor, the Gullah Geechee and other African bondspeople adapted and created new cultural ties in a foreign land that they gradually made their own.

And when you had the house and land, the house and land, the house and land

And when you had the house and land, then you told me go.

I found a place to build my house, build my house, build my house

I found a place to build my house since I couldn’t go back home.

After nearly 250 years of endurance and resistance, African Americans finally took their freedom in the wake of the Civil War. But the question of where and how approximately four million freedpeople would live was hotly contested. These next lines of “Build a House” convey how freedpeople navigated a nation hostile to the notion of co-existing with Black Americans. The idea of colonization—sending free African Americans to Black countries like Haiti or Liberia—had gained ground in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Espousing the belief that an interracial American society was both undesirable and untenable, proponents of colonization, which included figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Henry Clay, imagined that deporting the Black population could be a simple solution. Frederick Douglass frequently decried colonization as an attempt to evict the Black population from their rightful home. For the most part, Black Americans rejected colonization schemes, instead advocating for access to land and equal rights under the law. Across the South, freedpeople developed hundreds of free towns after slavery and the war ended, building homes, churches, and schools to support their families and the community at large. Each of these locales became hubs of political activity, as Black male enfranchisement paved the way for Black men to hold local, state, and federal office.

You said I couldn’t build a house, build a house, build a house

You said I couldn’t build a house, so you burned it down.

So then I traveled far and wide, far and wide, far and wide

And then I traveled far and wide until I found a home.

You could probably close your eyes and see a film reel depicting the violent efforts to overthrow Reconstruction as Giddens vocalizes these next lyrics. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, white southerners deployed a legislative and extrajudicial arsenal to undermine the political and social gains achieved by their Black neighbors. These lethal weapons included Black codes and Jim Crow laws, lynching (primarily, but not exclusively, of Black men), and the burning of Black homes and communities from Memphis, Tennessee, to Colfax, Louisiana, to Rosewood, Florida, to Tulsa, Oklahoma. These “southern horrors,” as termed by Ida B. Wells, sparked one of the largest movements of people in US history. In a mass refusal to accept the norms of a racially regressive South, Black Americans made a dramatic bid for freedom. They left. Between 1910 and 1970, more than six million Black Americans exited the South, seeking greater economic opportunities, a respite from domestic terror, and a safe place to raise their families. In his poem, “One-Way Ticket,” Langston Hughes summed up this Great Migration, writing “I pick up my life and take it on the train to Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Seattle, Oakland, Salt Lake; any place that is North and West—and not South.” This new urban Black population reshaped cities across the country.

I took my bucket, lowered it down, lowered it down, lowered it down

I took my bucket, lowered it down, the well will never run dry.

You brought me here to build a house, build a house, build a house

You brought me here to build a house. I will not be moved.

For Black Americans, the cycle of displacement, relocation, and planting new roots didn’t end in the mid-20th century. Black urban and rural communities continue to combat issues like gentrification and environmental pollution today. But the closing lines of “Build a House” are a powerful reminder that Black communities continue to tap into the reservoir of resistance and resilience with which each new generation has met their respective challenges.

The final repeated words of the song, “I will not be moved,” pay homage to “We Shall Not Be Moved,” a protest song popular during the Civil Rights Movement that was adapted from an African American spiritual. Widely sung across the South in the 1960s, “We Shall Not Be Moved” became a message of solidarity among activists and a message of defiance to the perpetrators of injustice. “Build a House” joins this rich canon of music that Black Americans have crafted and called upon to reckon with the past and fight for a better future. With “Build a House,” Giddens artfully retells a history not just of tribulation but of triumph, not just of persecution but of perseverance. Above all, this piece reminds us of Black Americans’ unwavering determination to cultivate spaces of safety and belonging—spaces otherwise known as home.

Bethany Bell is a master’s student at the University of Virginia. She tweets @bethanyannbell.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.