The June 2025 issue of the American Historical Review features articles on opium, terminology for slavery, and counterrevolution, and includes contributions on the concept of “Big Asia,” searchability in the age of mass digitization, and the use of archival databases in the classroom.

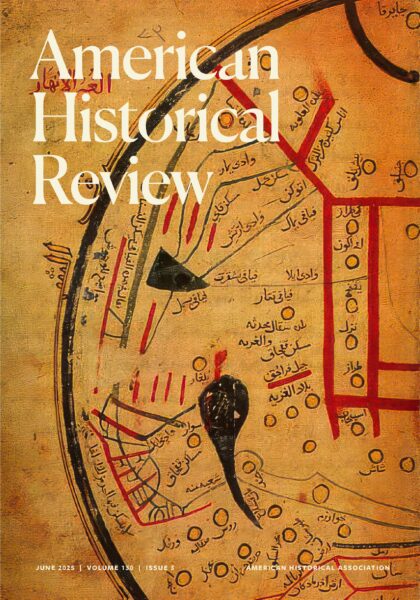

This issue’s cover features an 11th-century world map that was published as part of Mahmud al-Kashgari’s Diwan Lugat at-Turk (The Compendium of the Turkic Dialects). The representation is oriented with the East at the top and centers the Turkish-speaking areas of central Asia. Adjustment to the scale also gives the impression that central Asia is magnified in the center. In the History Lab forum “Big Asia: Rethinking a Region,” the contributors consider the concept of a unified “Asia” and new approaches on the macro scale, pushing readers to adjust their own view and framing of “Big Asia” and prompting a reexamination of globalization and Asian history.

The issue begins with “The Opiated Ocean” by Alastair Su (Westmont Coll.). Su analyzes the role and regulation of opium in the 19th-century trata amarilla (“yellow trade”) of Chinese indentured workers (“coolies”) to the Caribbean. Su explains that while scholars have presented different reasons for opium’s ubiquity—from a form of recreation to a method of social control—he argues that its widespread use among the indentured workers highlights the correlation between substance dependence and infectious diseases. The genesis of regulations that shifted the provision of opium from discretionary to mandatory was rooted in efforts to stave off seaborne epidemics. Opium, Su explains, suppressed symptoms of diseases, especially dysentery and typhoid, and low-cost contract labor was too profitable not to institute polices to promote workers’ survival, if temporary, at this intersection of labor and global migration.

In “Mesopotamian Words for ‘Slave,’” Seth Richardson (Univ. of Chicago) traces the linguistic ambiguity surrounding terms for slavery in social, economic, and legal Mesopotamian contexts. He shows that “terminological questions about what slavery is are as old as the terms themselves.” Ambiguity of language profoundly shaped and informed socioeconomic notions of slavery, and definitional vagueness that permitted the nonspecific meanings for personal status, legal object, and economic institution in turn enabled slavery to change and thrive across the ages. Richardson argues that lexical ambiguity was a strategy that enabled the practice of slavery in legal and commercial practice, untroubled by social logic or critical definitions.

Nathaniel George (SOAS Univ. of London), in “‘Survival in an Age of Revolution,’” examines the political biography of Lebanese philosopher and statesman Charles Malik, primarily known as the principal author of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to historicize counterrevolution in the 20th century. George argues, “While great effort has been invested in analyzing the role of revolutionary intellectuals in history and theory, much less attention has been paid to the counterrevolution and its guides.” Countering the presumption that in the era of decolonization, anticolonial efforts were the default, George shows that Malik and the struggle for the Lebanese state can serve as an “instructive window into the global battle between imperial, revolutionary, and counterrevolutionary conceptions of sovereignty and political representation.”

The History Lab begins with the forum “Big Asia: Rethinking a Region.” Seven authors, Sakura Christmas (Bowdoin Coll.), Amy Beth Stanley (Northwestern Univ.), Nile Green (Univ. of California, Los Angeles), Mustafa Tuna (Duke Univ.), Rachel Leow (Univ. of Cambridge), Melissa Macauley (Northwestern Univ.), and Jeffrey Wasserstrom (University of California, Irvine), trained in different subfields of Asian history, discuss the constructed idea of Asian geocultural unity, sketching how the idea of “Asia” was disseminated across the different lands it labeled and conceptually unified. Green, the forum’s organizer, remarks that it “is an apt moment to grapple with the multiple ways in which that biggest of continents is conceived—especially in its own languages.” Four shorter commentaries from Hyunhee Park (John Jay Coll.), Ruth Mostern (Univ. of Pittsburgh), Cemil Aydin (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Sebastian Conrad (Freie Univ. Berlin) conclude the forum.

Seven authors trained in different subfields of Asian history discuss the constructed idea of Asian geocultural unity.

The Lab also includes “In Defense of the Search Bar,” in which Hannah Frydman (Harvard Univ.) looks to the “infinite archive”—the ever-expanding terrain of mass digitization projects—and its search capabilities. Challenging assumptions that full-text search can lead to decontextualized history, she argues that the “anarchy of the mass digitization and its search bar” can push researchers to “think outside of long-established classifications.” Using the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s digital library, Gallica, as a case study, Frydman proposes that queer history provides an opportunity to deconstruct and reconstruct the archive and its categories.

Continuing the collaboration between History in Focus, the AHR podcast, with other historical podcasts, Daniel Story (Univ. of California, Santa Cruz) teams up with Kate Carpenter (Princeton Univ.), host and producer of Drafting the Past, to discuss the craft of writing history. They highlight the approaches, themes, and challenges that have come up in conversations with guests, while unpacking the minutiae of both the writing process and podcast interviews.

The Lab includes the latest module for the #AHRSyllabus project with Edward Cohn’s (Grinnell Coll.) “Teaching Historical Thinking Through a Primary Source Database.” Cohn shows how instructors of intro-level college history classes can work not just with preselected primary sources but with an entire archive of documents—an online collection of oral history transcripts about everyday life in the Soviet Union known as the Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System. The module includes a lesson plan introducing students to the collection and a writing assignment to help hone their skills in using and synthesizing archival material.

The Lab concludes with two History Unclassified essays. In “Las Que Van Quedando en el Camino (The Women Who Are Left by the Wayside),” Thomas Miller Klubock (Univ. of Virginia) examines a recently discovered oral history interview of a woman peasant (campesina) and leader of Chile’s 1934 Ránquil rebellion, Emelina Sagredo, with Chilean playwright Isidora Aguirre. In reviewing the interview and Aguirre’s dramatization of the Ránquil rebellion, Klubock considers the sources’ importance alongside the ethical questions that abound regarding subjects’ privacy and the nature of writing a history of largely illiterate women. Pernille Ipsen (Univ. of Wisconsin–Madison), in “Writing My Seven Mothers Back Together,” recounts her experience writing and publishing a memoir of the seven feminists she called mother during her childhood in Denmark in the early 1970s. She details the difficulties of this work and of revisiting the conflicts that drew the women apart, as well as the solace she found in ultimately reminding her mothers of “the feminist alliances they formed across their differences.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.