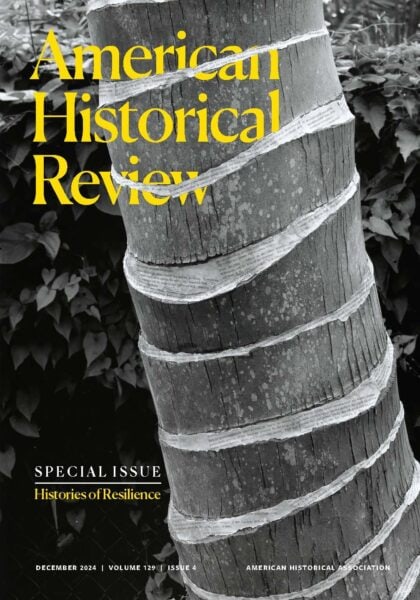

With the December 2024 issue, the American Historical Review inaugurates the annual publication of a special issue. Each will advance innovative themes, approaches, and methods to the past that can contribute to reshaping contemporary historical practice. This issue addresses histories of resilience.

The image from Forest, on the cover of this “Histories of Resilience” special issue of the AHR, is part of a set of 16 large-format gelatin silver prints that capture temporary installations developed by the Singaporean-born artist Simryn Gill in the late 1990s. These installations involved grafting strands of pages from books and meticulously wrapping them onto trees and plants in tropical landscapes. With the project, Gill addressed issues around the decolonial and resilience, selecting English language works with colonial associations and former colonial military sites in Malaysia as the locations for her installations. Page fragments were intentionally left to decay and return to the raw fibrous material from which books are made. In exploring the epigones of empire in postcolonial Southeast Asia, Gill uncovers how the English language was used as a colonial tool for exploiting natural resources and fostering inequalities. But she also suggests that, in the end, the language forced on colonial subjects was overwhelmed by the resilience of local ecosystems.

Overseeing the issue was an editorial collective of Shelly Chan (Univ. of California, Santa Cruz), Yoav Di-Capua (Univ. of Texas at Austin), Catherine Cymone Fourshey (Bucknell Univ.), Joshua L. Reid (Univ. of Washington), and Wendy Warren (Princeton Univ.). They encouraged contributors to explore how resilience has been expressed historically in various cultural contexts and informed the ways that communities and nations rebuilt or crafted futures after, for instance, slavery, civil war, displacement, or environmental disaster.

The resulting articles offer rich understandings of how historical context and contingency shape and inflect resilience. Opening the issue is “Resilience in Environmental History Discourse” by Lee Mordechai (Hebrew Univ. of Jerusalem) and John Haldon (Princeton Univ.), who rethink the use of resilience in histories of environmental and climatic change. With historians the latecomers in engaging resilience theory, medievalists Mordechai and Haldon review resilience as a paradigm of institutionalized knowledge across the disciplines.

Two articles examine Asian histories. In “Lines of Fate,” Ian M. Miller (St. John’s Univ.) and Chris Coggins (Bard Coll. at Simon’s Rock) explore protected fengshui forests in subtropical southern China over the last millennium. Combining textual, ethnographic, and scientific evidence, Miller and Coggins examine how these forests have fostered community resilience and sustainability over centuries. Their article is accompanied by a visual essay that details their fieldwork practices. Alex Jania (Univ. of Chicago) turns to Japan in “Between the Emergency and the Everyday,” exploring the history of Miyagi Prefecture’s tsunami memorial halls. In investigating the challenges of using memorials and collective memory to build resilience to future and recurring threats, he also examines new memorials, including a collaboration of architects, designers, and historians to build more resilient structures that reflect ideas of continuity and adaptability.

Indigenous histories are the subject of several articles. While the history of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) has often been told as a cautionary tale of the destructive tendencies of civilization, Gregory T. Cushman (Univ. of Arizona), Trisha Jackson (PrairieFood), and Johannes J. Feddema (Univ. of Kansas and Univ. of Victoria) call the island a “parable of survival, adaptation and resilience” in their “Ecologies of Resilience.” The authors showcase the complex ways Rapanui peoples encoded historical and ecological knowledge and maintained an archive over generations.

In “History on the Lost Coast,” Kathleen C. Whiteley (Univ. of California, Davis) exemplifies how historians can use a resilience framework to craft narratives that highlight Indigenous agency amid the cacophony of settler violence. She bookends her intervention around a 2019 Wiyot Nation reclamation of over 200 acres on Northern California’s Tuluwat Island, the site of a catastrophic massacre in 1860. Like other scholars of Indigenous resilience, Whiteley draws from Wiyot ways of knowing and remembering the past, including storytelling and oral accounts, many of which were collected in the Wiyot History Papers and supplemented with photos.

Finally, California’s Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe (NCRNT) is the subject of Megan Renoir (Univ. of Cambridge) and Shelly Covert’s (NCRNT) “Recognition as Resilience.” The story of NCRNT, a nation that is not federally recognized, highlights how Indigenous resilience can become something considerably more than just a tool for survival. Renoir and Covert highlight resilience in practice, especially through NCRNT collaborations with educational institutions, NGOs, and state and federal offices to combat historical inaccuracies and to address contemporary environmental issues.

The issue offers rich understandings of how historical context and contingency shape and inflect a variety of forms of resilience.

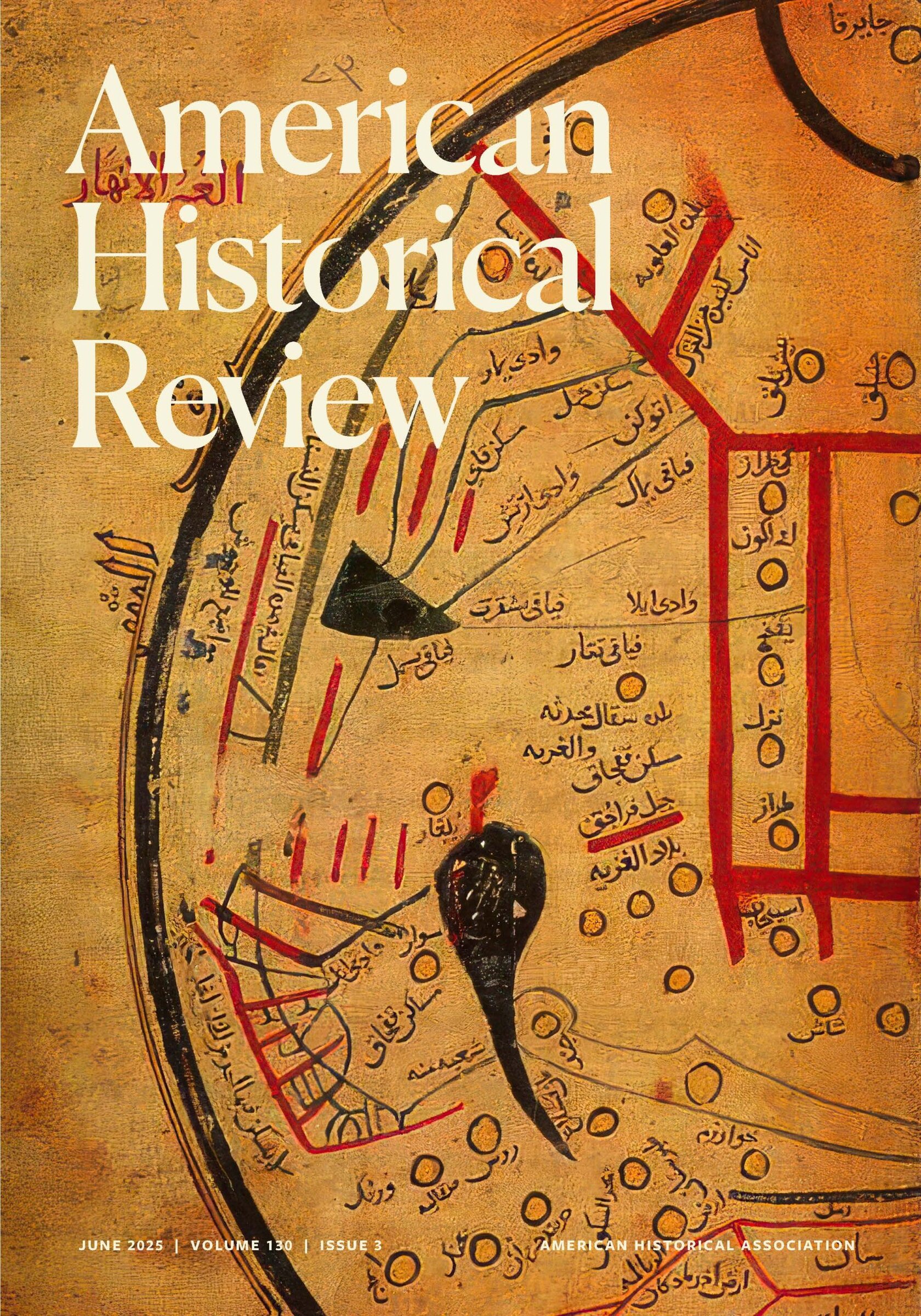

Other articles examine the role of resilience in relationships between citizens and the state. In “State-Led Development and Migrants’ Resilience in the City of the Forest,” Thaís R. S. de Sant’Ana (Univ. of Houston–Clear Lake) analyzes strategies deployed by workers in the Brazilian state of Amazonas from the 1910s to the 1930s as they repeatedly maneuvered to avoid state-controlled labor projects. Sant’Ana draws on interviews and newspaper articles to move beyond conventional narratives about Amazonia and offers readers new possibilities for understanding the region’s complex socioeconomic transformations and growth.

Tammy Wilks (Univ. of Cape Town) in “Kenyan Nubians and the Myth of Nubian Resilience” examines how resilience informed claims for citizenship by a stateless community in Kenya in the late 19th century. She traces a particular myth to illustrate how the notion of Nubian soldiers’ exceptionalism informed, authorized, and, at times, undermined the colonial project in Kenya as well as the political realities of Nubian soldiers.

In “The Lancashire Plague Petitions,” Rachel Anderson (Durham Univ.) explores an untapped archive of petitions for poor assistance to the Lancashire Court of Quarter Sessions, written following plague outbreaks in England during the early 17th century. Through an analysis of select petitions, Anderson achieves what she calls a “street-level perspective of an early modern society recovering from moments of intense crisis.” Anderson joins a body of scholarship critical of resilience studies that emphasize individual skills and traits over the importance of community and external assistance.

The issue concludes with three digitally focused projects that explore additional dimensions of how resilience works as a historical and analytical category. Jessie Ramey (Chatham Univ.) and Amelia Golcheski (Emory Univ.) in “Love, Hope, and Joy” use the career of activist Kipp Dawson to examine how resilience can operate in social movements even as they encounter setbacks, losses, and violent repression. Ramey and Golcheski’s multimedia, open education website, Kipp Dawson: The Struggle Is the Victory, develops the idea of “radical collaboration” and focuses on movement networks, interconnections, and affects. Their contribution includes an introduction to Dawson’s work and a video on the making of the site.

Bob Reinhardt’s (Boise State Univ.) “Exploring Submerged Resilience” reflects on the Atlas of Drowned Towns, a public digital history project that seeks to identify, explore, and interpret the histories of places in the United States that moved or disappeared to make way for big dams. Currently under development and focused on 13 dams in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, the artifacts, stories, and memories shared with the Atlas reveal acts of resistance, insistence, and persistence in the past, and those acts of sharing and participation themselves provide opportunities to express and define resilience in the present.

In his textual essay “Setting History in Motion” and video essay “Visualizing Resilience from the Periphery,” Daniel McDonald (Univ. of Oxford) explores what he sees as the central role of the visual in the construction of social resistance in Brazil during the civil-military dictatorship (1964–85). Infused with images of urban landscapes, public life, neighborhood organizing, and open protest, social movement paraphernalia provided a visual lexicon, he argues, that helped activists make sense of substantial inequalities in urban housing, employment, and social services as well as envision new forms of protest and direct action. The video essay assembles these dispersed illustrations along with soundscapes and clips from films into distinctive phases of a metanarrative connecting the rise of the megacity to collective social action.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.