What is the opposite of entropy, a trend toward disorder and chaos? Tropy, as Stephen Robertson, a cultural and social historian at George Mason University (GMU), and his team decided while brainstorming names for their new research management tool.

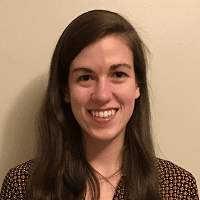

Tropy allows researchers to organize and describe photos taken in archives. Abby Mullen

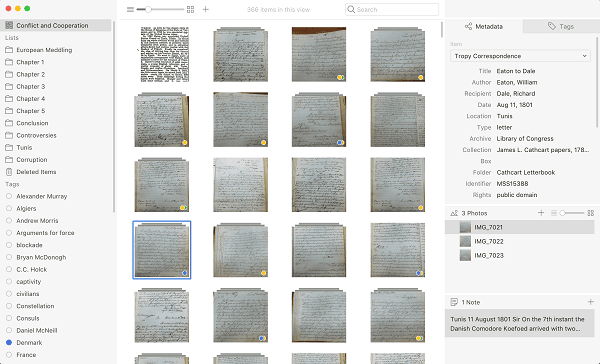

Tropy is a free, open-source desktop application designed to help researchers organize and describe the photos they take in archives in intuitive and useful ways. It allows users to group photos of research materials, annotate images, add metadata, export to other applications, and easily search their collections.

Tropy was created by Robertson, Sean Takats, and their team at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at GMU, with developers based in Vienna, Austria. Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the first full version of the application was released to the public in October 2017. Since then, according to project manager Abby Mullen, Tropy has been downloaded over 4,500 times. The software was designed to fill a specific hole in the research process—when a researcher returns home from working in the archives with thousands of photos and can’t quite figure out how to organize them. Tropy’s organization system promises to bring order to this chaos.

The need for an app like Tropy became apparent to Robertson, co-principal investigator with Takats on the project and director of the Roy Rosenzweig Center, during the last decade, as more and more archives started allowing researchers to use digital cameras in their reading rooms. “It’s only really in the last 10 years, maybe even a little shorter than that, that it’s become more standard practice for archives to allow you to take photographs,” explains Robertson. “Even 10 years ago, it was a toss-up whether an archive was going to let you do it.” Now the practice of taking photos of archival documents is commonplace and has fundamentally changed how historians conduct archival research. And Robertson hopes that historians will turn to Tropy for help with that early stage of the research process.

Tropy is designed to be easy to use, even for people not particularly comfortable using digital technology. Detailed documentation on Tropy.org describes what researchers can and cannot do with the application, provides instructions for basic use of the software, and answers common questions. For issues not addressed in the documentation, an active forum allows researchers to ask questions, troubleshoot specific problems, and suggest changes or ask for additional features.

Robertson says that using Tropy makes scholars “more self-conscious” about how they do research. They can use customizable templates to describe each photo, which in turn encourages them to think carefully about metadata and its potential uses. This metadata can include information about when and where a document was created, whether the document is under copyright, what collection the document belongs to, or anything else that a researcher desires to input. Tropy is available in English, French, and German, with a Japanese version on the way. The interface itself can work with multiple languages and includes the ability to write top to bottom and right to left. Robertson believes that the metadata scholars create in Tropy can help them think differently about their sources and their research. Metadata, he says, can give scholars “collection-level perspective” that can help them zoom out, look across all of their research, and see the “big picture” of what they’ve got.

Tropy has also inspired discussions about archival research practices and, surprisingly to Robertson, revealed that graduate training in history frequently does not teach students “the method of doing research in archives.” Robertson says his team has “been involved in a number of interesting discussions” about how scholars can make changes to their research practices in archives by thinking about how they would use Tropy to describe and organize their sources.

The feedback about Tropy thus far has been almost uniformly positive. Robertson says that people have been “enthusiastic” both about the idea of having software like Tropy and about the software itself. User feedback, says Robertson, confirms that scholars have needed something like it for a long time, with many “bemoaning all the projects they did without this that are now infinitely easier to imagine.”

Paula R. Curtis, a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Michigan, finds Tropy “easy to learn” and an “excellent way to centralize” her sources and notes. The sources for her dissertation research into the use of forged documents in late medieval Japan are spread across many archives, and Curtis appreciates how Tropy lets her “upload and organize multiple sets of photographs under a single project and tag them so I can view objects together by type, source, author, keyword, or other characteristics across archival folders.” She finds Tropy’s ability to allow users to add metadata for multiple documents simultaneously particularly useful. Curtis tells Perspectives that “being able to place annotations directly on images has been wonderful for digging into the materiality of my sources as I think about copying practices and counterfeits.” Curtis notes that Tropy is “a little buggy” loading on a PC, but says that she’s never lost data because of this.

Robertson believes that the metadata scholars create in Tropy can help them think differently about their sources and their research.

Sarah Werner, a selfdescribed “book historian, digital media strategist, and Shakespeare scholar,” has also found Tropy useful for a project on the production of early printed books. Werner tells Perspectives that Tropy was crucial for both collecting images to use in the book and “even more importantly, to make sure that I have accurate metadata for those images—what books they are of, including what pages are pictured, but also what libraries took the images, what the shelfmarks are, what the URLs are of the images, and under what terms the images were released.” For this project, Werner worked with images taken by other people, as opposed to her own archival photographs, so she needed to update the metadata template on Tropy. Werner appreciates the ease with which she could create new templates and import new metadata vocabularies.

A number of libraries and workshops have already started embracing Tropy. In January of this year, the Digital Humanities Innovation Lab at Simon Fraser University offered a workshop called “Collecting, Organizing, and Describing Archival Research,” which focused on using Tropy to record and organize data. Shannon Supple, curator of rare books at Smith College Libraries, also recently included Tropy in her newresearcher guide, saying that the program would help new visitors “track their own research so that they can return to snapshots from the reading room later and understand where the images came from and why they thought them important at the time.” She hopes that a tablet or smartphone version will be available soon, as well as the ability to automatically pull metadata from catalog records.

With more users, the team at the Roy Rosenzweig Center is constantly looking to make improvements to the software. Mullen says that the team is “actively responding to feedback” from users, “always improving our product, one small release at a time.” A major recent release included the ability to export to Omeka, an open-source online publishing platform developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center in 2008. The release also included advanced photo-editing features that many users had requested.

One major complaint people have about Tropy is its inability to work with many popular image file formats. Currently, Tropy only allows researchers to import photos as JPEGs, PNGs, and SVGs. Researchers accustomed to using PDFs cannot import those files into Tropy. Robertson notes that the ability to import PDFs is not currently in the works. Instead, if they can get funding, the priority for the next step in developing Tropy is integrated cloud storage, which would allow for more collaboration. Robertson says that they were somewhat surprised by how many people wanted to use Tropy for collaborative projects. Archaeologists, who would like to be able to collaborate on photographs of their digs on Tropy, have especially been asking for this feature.

In the future, Robertson hopes that organizations digitizing their collections might also consider incorporating Tropy into their work-flows. From the beginning, Robertson says, the Tropy team has imagined how the software could be a “bridge between the digitization that researchers are doing and the digitization that institutions are doing.” Researchers already digitize archival material when they take photographs of it; institutions that lack the resources to mount full-scale digitization projects on their own might partner with scholars who could, using Tropy, provide digital images of a collection, complete with metadata, to the institution. Robertson says he’s already had discussions with institutions interested in creating metadata “templates for their own collection in order to make sure that the researchers describe them in a standardized way.”

Now that Tropy is available for use, its team is working to get the word out. Most current users learned about Tropy through colleagues or via Twitter. Some were already dedicated users of other programs such as Omeka or Zotero coming out of the Roy Rosenzweig Center, and were excited to try the new application. Robertson’s next target audience is researchers who might not be on Twitter: “people who don’t consider themselves digital historians but who are taking digital photos.”

Update, March 26, 2018: This article has been updated to note the name of Tropy’s other principal investigator, Sean Takats.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.