On December 3, 2015, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced the removal of the last official gender barrier in the US military. Within 30 days of his announcement, women will no longer be barred from any combat role in any service branch. The news should not be surprising given that women have served in the armed forces formally for nearly three-quarters of a century. 2015 was a year of many firsts for servicewomen—the Navy began assigning enlisted women to serve on submarines in June, and in August women graduated from both the Army’s Ranger School and the combat engineer program.

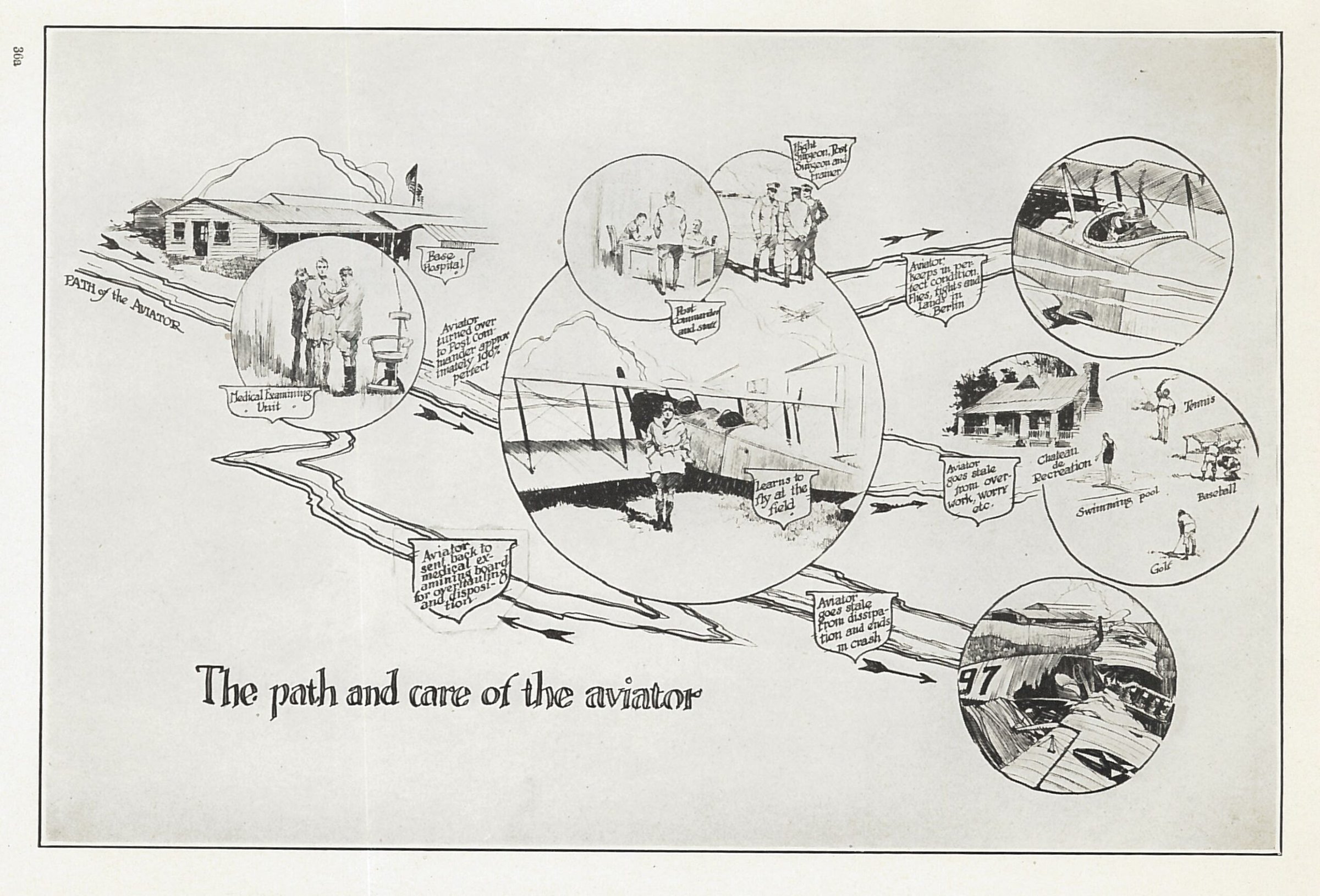

Carter’s decision makes sense given the complex nature of modern warfare. All military personnel—regardless of gender—serve worldwide in roles that put them in some proximity to combat, even if their jobs lack such a designation. When it comes to national defense, there is no way to guarantee that serving even in “safe” jobs or zones will keep service members away from danger. However, it is important to note that this is nothing new. Civilian women ferrying planes as members of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) in World War II faced the same dangers as male soldiers flying planes—in fact, 38 WASPs died in this line of duty. Women served in Vietnam throughout the Vietnam War, often in close proximity to fighting, and during the Gulf War, 15 women died in service, and two became Iraqi prisoners.

Members of Congress first debated the appropriateness of women’s military service after World War II. Supporters argued that keeping women in the military was about making the best use of Americans who serve, regardless of gender. Colonel Mary Hallaren, head of the Women’s Army Corps, argued just this point in 1947. “When the house is on fire,” she explained, “we don’t talk about a woman’s place in the home. And we don’t send her a gilt-edged invitation to help put the fire out. In the future, we shall be concerned with her utilization.”1

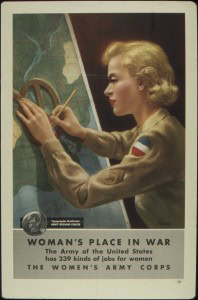

Despite Hallaren’s approach, the 1948 Women’s Armed Services Integration Act established separate, gendered spheres of military service. Defense officials embraced the idea that femininity and military service were compatible, categorizing servicewomen as America’s finest ladies, taking their place alongside the best of American manhood. This Cold War-era construct defined women’s service for three decades and lingers today in the discourse regarding who serves and in what ways.

By the 1970s, the end of the draft, the early success of the Equal Rights Amendment, and servicewomen’s own efforts to fight limitations led to drastic changes in the military. Within a few years, several barriers disappeared: mothers could serve, women could join the service academies, and women’s components such as the Women’s Army Corps disappeared. By 1978, few limitations remained, and the more recent image of rifle-carrying, camouflage-clad women began to appear.

That was 37 years ago. Why has it taken so long for the final combat barriers to fall, especially in light of Desert Storm and post-9/11 conflicts? Those who argue that this newest change is too radical overlook the slow pace of change in the armed forces. Defining service around gender prescriptions may have helped Americans accept the idea of daughters and mothers in national defense, but also ensured servicewomen’s secondary status. As the Cold War ended, women increasingly took on jobs barred to them just decades before, even as new regulations tried to maintain the combat divide.

Today’s critics of removing combat restrictions cite military effectiveness as a justification against what they see as a radical change in military policy. Carter rightly points out that the decision reflects the fact that women already serve in combat roles. In Carter’s eyes, removing combat barriers is not about pressing forward with a specific feminist agenda, despite critics’ concerns. Carter’s announcement echoes Hallaren’s point that there should be no obstacles to helping the military find and use the best people for any job.In 1947, Colonel Hallaren was at the cutting edge in thinking about women’s roles in national defense. Nearly 70 years later, Secretary Carter’s announcement should pave the way for women’s utilization based on ability and military need just as men have always experienced.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

- Hallaren Statement on S.1103, 1947, 1-2. Mary Hallaren Collection, US Army Women‘s Museum, Fort Lee, VA. [↩]

Tanya Roth teaches sophomore 20th-century world history and junior AP US history at MICDS, an independent college preparatory school in St. Louis, Missouri. She earned her PhD from Washington University in St. Louis in 2011 with research on women’s integration into the US military. Find her on Twitter @DoctorTonks.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.