In September 1917, Georges Guynemer, one of France’s best fighter pilots, exhibited a “dangerous” nervousness that worried his fellow fliers. His wingmen telephoned commanding officers urging them to pull the French ace from combat duty so that he could rest. But Guynemer took matters into his own hands. On September 11, Guynemer engaged German fighters for the last time and did not return to the aerodrome. The legendary pilot’s fate was unknown until October, when the German air force declared that one of its pilots killed the Frenchman. Nearly a year after his death, journalist Laurence Driggs remembered Guynemer as the “Ace of Aces” and “a marvelous if not a miraculous human being.”

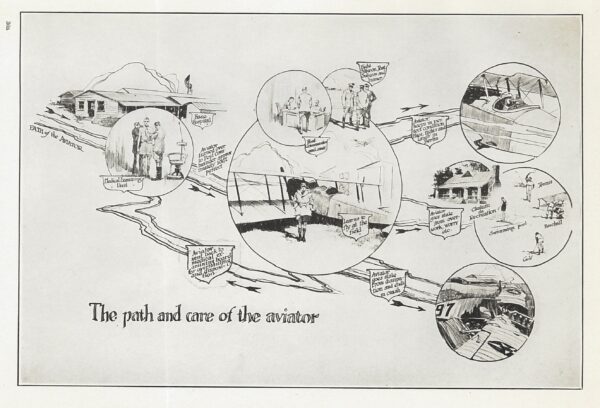

As “The Path and Care of the Aviator” shows, aviators who “keep in perfect condition” will fly and fight, while those who went “stale from overwork, worry, etc.” need recreation or, due to “dissipation,” will end in a crash. US War Department, Air Service Medical Manual(Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 36a. Public domain.

American flight surgeon William Wilmer opined on Guynemer’s mental health and death in his 1919 book, Aviation Medicine in the A.E.F. In the days before his death, Wilmer wrote, Guynemer’s wingmen did not even recognize him because of a perceived psychological distress. Wilmer asserted that if an American flight surgeon, a trained medical doctor who lived and interacted with the squadron, had been serving with Guynemer, he likely would have recognized the Frenchman’s condition and treated him immediately.

Today, American military personnel and civilians alike worry about the mental health of combat veterans. Studies show that many veterans suffer psychological distress due, in part, to the highly masculine culture of military service. In blockbusters such as Top Gun (1986) and The Right Stuff (1983), masculinity and the “flight suit attitude” has also been intrinsically connected. This connection dates back to the air force’s earliest days. More importantly, for the nascent US Air Service, this “martial masculinity” dictated how medical personnel treated and diagnosed the psychological issues that plagued many pilots.

A connection between “physical fitness” and “nervousness” intertwines an important trait of early-20th-century conceptions of masculinity with the psychological symptoms of aerial combat. Indeed, as time and their war experience demonstrated, medical personnel understood the psychological consequences of aerial warfare based on contemporary social and cultural frameworks. During this period, American society not only emphasized the importance of living up to Progressive Era ideals, such as being temperate and sexually moral, but also the need for men to have fit, muscular bodies. In a country increasingly infatuated with competitive sports, Americans perceived aerial combat itself as a game where two men fought each other to the death in a new competitive arena of warfare. To psychologically survive this game, fliers needed to live up to the masculine standards of the era.

Americans perceived aerial combat itself as a game where two men fought each other to the death.

For the US Air Service, which became a branch of the US Army in 1918, “staleness” posed a new, distinct problem. While its symptoms are eerily similar to what scholars and doctors today consider acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or the contemporary diagnosis of “shell shock” that infantry men experienced, flight surgeons considered staleness to be distinct. They argued that the problem was rooted in the low-oxygen environments of aerial combat, and thus, had a physical cause. According to Wilmer, these symptoms included loss of appetite, “dread of the morrow,” a sense of “fatalism,” nightmares, jumpiness, and a lack of confidence. Medical manuals and other documents detail how doctors perceived staleness as a severe threat to the Air Service’s ability to fight a war and maintain efficient fliers.

For medical personnel, these symptoms were detrimental to the airman’s efficiency and ability to fly in combat. The Air Service ushered in multiple programs and treatment regimens, all of which perpetuated the era’s focus on proper moral hygiene, physical fitness, and the cultivation of an athletic and competitive spirit. Medical personnel urged fliers to maintain “clean-living” habits by abstaining from “dissipation”—engagement in intemperate or sexually immoral behavior. Fliers needed to live, as the Air Service’s medical consultant Thomas R. Boggs put it in his “Report of the Medical Consultant, Air Service,” “the gospel training and clean living.” Airmen also needed to maintain high physical fitness standards. Flight surgeons emphasized that “strenuous exercise” would improve fliers’ cardiovascular health and thereby prevent high altitude’s effects on their brains and psychological health. For those who nonetheless suffered from staleness, flight surgeons prescribed competitive sports as a form of treatment. They urged pilots to box, play baseball, and compete in other sports to maintain their aggressive edge. Thus, moral and physical health, along with competition, influenced the way that the medical officers perceived airmen’s psychological wellbeing.

Air Service medical personnel relied on society’s notions of masculinity to treat, prevent, and rehabilitate men experiencing psychological distress.

The US Air Service’s time in World War I was relatively brief, but its pilots endured enough time in combat to experience the psychological consequences of aerial warfare. With the fields of psychiatry and psychology still in their infancy, Air Service medical personnel relied on society’s notions of masculinity to treat, prevent, and rehabilitate men experiencing psychological distress. These flight surgeons established precedent that influenced the Army Air Force’s approach to airmen’s mental health in World War II, when masculinity once again became an important factor in determining the treatment and regulation of psychological casualties in the 1940s.

This history also has contemporary implications with support from modern-day science. As the 2020 study “Traditional Masculine Ideology, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Severity, and Treatment in Service Members and Veterans” argued, many military personnel continue to struggle with psychological issues because they feel that they fail to live up to a military culture that they see as highly masculine.

If the story of staleness and the Air Service shows us anything, it is that contemporary social and cultural beliefs, particularly concerning gender norms, shape the diagnosis, experience, and treatment of mental health issues. Maybe it is time to rethink the technological, social, and cultural roots of the perceptions of war trauma. As we do, we will learn how to better understand mental health issues within a societal context, destigmatize these illnesses, and better treat those who live with them.

The views expressed in this article, book, or presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Jorden Pitt is an instructor of history at the United States Air Force Academy and held the AHA Fellowship in the History of Space Technology in 2022–23.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.