A survey by the Coalition on the Academic Work Force (CAW), a consortium of 25 disciplinary societies concerned about the use and treatment of part-time and adjunct faculty, provides compelling new evidence on the use and treatment of part-time and adjunct faculty (as well as graduate students). The results highlight the dwindling proportion of full-time tenure-track faculty teaching in undergraduate history classrooms, and provide solid evidence of the second-class status of part-time and adjunct employees.

The CAW (which includes representatives from the AHA and the Organization of American Historians) and the opinion survey organization Roper Starch drafted the survey in the spring of 1999 and mailed it in the fall. For the history discipline, the Roper Starch refined a representative sampling of 670 departments and institutions that had earlier been developed for the Modern Languages Association. The mailing list was specifically designed to improve the representation of two-year colleges, which are underrepresented in the annual survey of history departments conducted by the AHA. AHA staff then mailed and collected the responses, and Roper-Starch tabulated the results. The effort was made possible by a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The response rate was somewhat disappointing—just 46 percent overall—but technical staff at Roper-Starch judged the returns adequate to offer a basis for analysis. Two-year institutions had the poorest response rate—just 39 of 200 surveys sent to them—no doubt due to the significant proportion of institutions without departments or programs in history. In contrast, four-year institutions returned over 55 percent of their surveys, with more than 60 percent from departments at universities conferring doctoral degrees.

The survey requested data on salaries, benefits, and institutional support for full-time non-tenure track and part-time faculty. The survey findings also provide important new data on the number of faculty (and graduate students) teaching in undergraduate classrooms.

Faculty Demographics

Figure 1

Over the past 20 years the proportion of part-time and adjunct faculty employed in history departments has increased sharply, as evidenced in Figure 1. In a survey of history departments conducted in 1980, the AHA found only 6.3 percent of history faculty were employed part time.1 However, both the CAW survey and a recent AHA department survey (for 1998–99) found the proportion of history faculty employed part-time had grown to over 24 percent (and significantly higher if graduate students are included, see Figure 2). Similarly, the proportion of history jobs without the possibility of tenure rose from 6.7 percent in the 1980 survey to over 25 percent in the CAW and AHA surveys.

Just over half of the history teachers at the responding institutions were employed full-time with tenure or on the tenure track. Of the remainder, 21.1 percent were part-time nontenure track, 20 percent were graduate teaching assistants, 4.4 percent were full-time nontenure track employees, and 1.3 percent were employed part-time, but either held tenure or were on the tenure track. Almost 80 percent of the responding institutions reported that they employed at least one part-time or non-tenure track employee in the fall of 1998, and just over 3 percent of the departments reported they had no full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty at all.

Figure 2

Two-year colleges reported that 58.5 percent of their history faculty was employed part-time, while four-year colleges and universities reported that 18.1 percent of their history faculties were employed part-time. However, the latter number is somewhat misleading, as an additional 22.1 percent of the individuals teaching in history departments at four-year institutions were graduate students.

Private church-related colleges and smaller liberal arts (BA-granting) departments reported that much higher proportions of their faculty were in full-time tenured or tenure track positions. At private church-related institutions, 60.2 percent of the history faculty was employed full-time with tenure or on the tenure track. This compares with 50.2 percent at public colleges and universities and 58 percent at other private institutions.

Similarly, 72.4 percent of departments that confer only the BA degree were composed of full-time tenured or tenure track faculty, as compared to 60 percent in MA programs, 53.3 percent in doctoral degree-granting programs, and 30 percent in programs granting associates degrees. Doctoral programs reported that 28.4 percent of the teachers on their staff were graduate students, and another 14.7 percent were part-time faculty.

Classroom Numbers

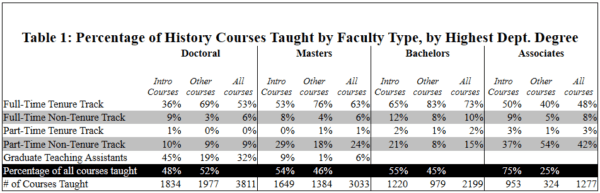

Table 1

Perhaps the most surprising finding in the survey is that full-time tenured/tenure-track faculty were teaching fewer than 50 percent of all introductory history courses (Table 1). Only 36.1 percent of the introductory courses at PhD-granting departments were taught by full-time tenured or tenure-track employees, while just 47.7 percent of the introductory courses at public institutions were taught by full-time tenured or tenure-track employees. At PhD-granting institutions, graduate students taught 45.4 percent of the introductory courses, while part-time faculty taught another 10 percent of the classes. Similarly, at public institutions, graduate students taught 18.4 percent of these courses, while part-time faculty taught an additional 23.2 percent.

Entry-level history students were much more likely to see a full-time tenured or tenure-track teacher at BA-granting departments, where they taught 65.1 percent of the classes. Full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty taught 53.1 percent of programs terminating with master’s degrees and 50.2 percent of introductory courses at programs conferring associates degrees. Part-time faculty taught 40.7 percent of the introductory level courses at departments granting associates degrees, as compared to 23.1 percent of programs granting bachelor’s degrees, and 29.4 at MA-granting programs.

Not surprisingly, the proportion of upper level classes taught by full-time tenure-track faculty was considerably higher, reaching just over 72 percent. Use of faculty at 2-year colleges diverged significantly from that average, where part-time faculty were employed to teach 54 percent of the upper-level history classes.

Institutional Support and Benefits

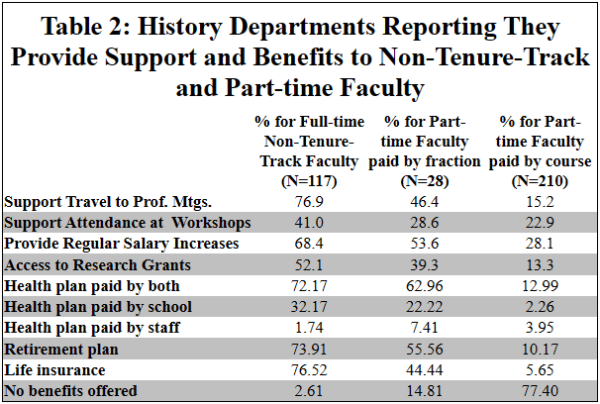

The CAW report also provides additional detail about the sort of the institutional support and benefits received by part-time and adjunct faculty (Table 2). While 2.6 percent of departments reported that they offered no benefits to their full-time nontenure track faculty, 77.4 percent of departments reported they offered no benefits to part-time faculty paid by the course.

Table 2

Seventy-one percent of the institutions employing full-time but nontenure track faculty and 62 percent of the departments paying part-time faculty a fraction of a full-time salary provided access for these faculty to a health plan copaid by the school and the faculty member. This compares with just 13 percent of institutions providing this benefit to part-time faculty paid on a per course basis. Similarly, 32 percent of the institutions with fulltime nontenure track faculty provided a health plan paid by the school, as compared to 2.3 percent of those having faculty paid by the course.

Not surprisingly, departments were more generous in providing other benefits to full-time nontenure track faculty, as 74 percent of institutions allow them to participate in the retirement plan and 76.5 percent provide access to life insurance benefits. This compares to just 10 percent of institutions providing part-time faculty paid by the course access to retirements, and 5.6 percent providing them with access to life insurance.

As with the benefits, full-time nontenure-track faculty also received considerably more support for their professional scholarship. Seventy-seven percent of the departments with full-time nontenure-track faculty provided them with support for travel to professional meetings, 52 percent provided access to research grants, and 41 percent provided support to attend workshops. In contrast, only 15 percent of the departments with part-time faculty paid by course offered such support, 13 percent provided access to research grants, and 22.9 percent supported attendance at workshops.

There was significantly less difference between full-time nontenure-track faculty and part-time faculty in the other “quality of life” issues, such as mailboxes and office spaces. Almost all the departments provide mailboxes, phone access, photocopying and library privileges.

There was a slightly wider difference in office space and computer use, as 81 percent of departments with full-time nontenure-track faculty reported that they had their own office, and 85 percent had access to their own computer. (Though it should be noted that a number of adjunct faculty in an AHA survey of part-time and adjunct faculty complained that these were typically older hand-me-downs).2 In 70 percent of the responding departments with part-time faculty paid by the course, these faculty had some access to a computer (though 51 percent only had access to a shared computer) and 75 percent provided shared office space.

Salary Data

Information on salaries further demonstrated the gap between fulltime nontenure-track and part-time faculty.

The average salary for a full-time nontenure-track faculty member was $37,222 per year. This is actually above the average for newly hired assistant professors in the most recent survey by the College and University Personnel Association.3 This salary differential can be attributed to the large number of one- and two-year endowed professorships that would fit under this category in the CAW survey. This analysis supported by further parsing of the salary averages, as the average salary at departments conferring the PhD—where these endowed positions typically reside—was $3,000 more than at other institutions.

The average salary for part-time faculty paid by the course was $2,480 per class. There were wide differences depending on the type of institution, as programs conferring associate’s degrees paid an average of only $1,694 per history course, compared to an average of $3,628 at PhD-granting departments. Similarly, the average at public institutions is well below the average at private institutions—$2,295 at public colleges and universities, compared to $2,664 at private church-related institutions and $3,304 at private independent colleges and universities.

Other Demographic Patterns

The growing use of underpaid and undersupported part-time faculty, and the waning of tenure lines poses a difficult problem for all new and prospective history PhDs. As data from other AHA departmental surveys indicates (see Figure 1), these trends have made it more difficult for women to strengthen their modest numbers in the history profession. In the AHA’s annual survey of departments for 1998–99, women held one-thirds of all history faculty jobs; a modest improvement over findings from 1979 and 1989, when males represented more than 80 percent of the faculty (and roughly comparable to the growing number of women with history PhDs).4

However, the women who gained academic positions were significantly more likely to be employed part-time than their male counterparts. The departments reported that 41 percent of the women they employed were part-time, as compared to 29 percent of men. While the proportion of men employed part-time increased almost five-fold over the past 20 years, the proportion of women employed part-time has increased almost six-and-a-half times over the same period.

The Association is presently working with other members of the CAW to develop a cross-disciplinary assessment of the data from the CAW surveys. The results of this larger assessment of humanities and social science fields should be available later in the year.

Notes

- American Historical Association. Survey of the Historical Profession, 1979–80: Summary Report, (Washington D.C., 1980: 11. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “Part-Time Teachers: The AHA Survey,” Perspectives (April 2000): 3. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “History Lags behind Other Disciplines: 2000 Salary Report,” Perspectives (September 2000): 3. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “History PhD Production Hits 20-Year High,” Perspectives (January 2000): 3. [↩]