In 2009, archaeologists uncovered a small copper medallion in a pit at Fort Shirley, Pennsylvania. Dated to the early 1750s, the trinket may have gone unnoticed were it not for the single phrase in Arabic emblazoned on its surface: “No god but Allah.” Its owner was most likely an enslaved person in the service of trader George Croghan. The Fort Shirley medallion has become part of a rare yet influential assortment of artifacts connected to the lives of enslaved Muslims in the United States. It shows how Islam has been part of the nation’s cultural history from its earliest beginnings.

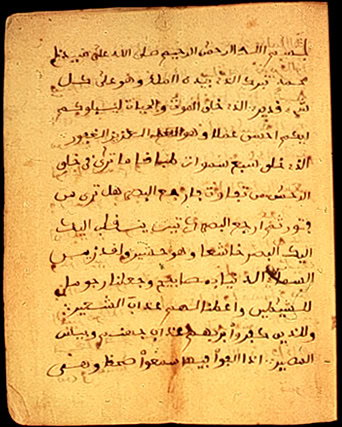

A chapter of the Quran written by the enslaved Islamic scholar Omar Ibn Said. Wikimedia Commons/Omar ben Saied

Not all Africans arriving in British North America came in a supposed “dark state of ignorance and wickedness, to the knowledge of God,” as proclaimed by Puritan minister Cotton Mather in a 1706 pamphlet in which he urged fellow Bostonians to Christianize and educate those they enslaved. By the time slave castles dotted the West African coastline in the 1500s, Islam had become well established in the region and was still growing, largely thanks to Arab traders from the north. While it is impossible to attain an exact number, historians estimate that up to 15 percent of enslaved persons brought to the United States were Muslims. Evidence of the country’s first Muslim inhabitants takes many forms: from oral traditions to physical artifacts like the Pennsylvania talisman.

“Islam is clearly not new to these shores, even if many American Muslims are,” said Professor Sally Howell, who serves as director for the University of Michigan-Dearborn’s Center of Arab American Studies. Howell spoke as part of a session, “Muslims in America: Denaturalizing Christian-centered Narratives of American History,” held on the last day of the AHA 2018 annual meeting in Washington, DC. The four-person panel discussed the communities Muslim immigrants and converts have formed in the United States and the historic challenges American Muslims have faced practicing their faith in both a national and global context. Howell continued, “Many Muslims themselves do not understand the extent to which Islam has a long history in the US, is part of our religious DNA, and yet is comfortably and genuinely Islamic.”

Within a few generations of arriving in the New World, the descendants of most Muslim slaves had stopped practicing their ancestors’ religion due to forced conversion to Christianity or the multitude of restrictions placed on their daily lives. Still, signs of these African Muslims can be found embedded within the historical record. It is not uncommon for slave registers from plantations to list Muslim names of Arabic origin. A 1774 tax record from George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate lists a “Fatimer” and “Little Fatimer” among the enslaved women, names most likely derived from “Fatima.” “In the United States in particular, there’s been such an over focus on Christianity among the enslaved, among African Americans,” said Ayla Amon, a curatorial assistant at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, adding that “it totally obscures the diversity of enslaved religious experiences.”

As African Americans moved out of the South in waves such as the Great Migration, they brought traces of Islamic practices with them, oftentimes unknowingly. Ring Shout, a religious ritual in which practitioners move in a circle and sing, “originally mimicked the ritual circling (or shaw’t) of the Kaaba in Mecca by Muslim pilgrims,” according to Amon. Some of the first blues songs, evolved from slave field hollers, show striking melodic similarities to the Islamic call to prayer. Howell has conducted research and interviews in Detroit, which saw the creation of several African American Muslim communities in the mid-20th century. Among some interviewees who had converted to Islam in the 1960s and 1970s, “there was this Muslim folklore, these Muslim cultural practices that had lingered in their families,” said Howell. Examples included one man whose grandmother fixated on washing ears and taking shoes off before entering rooms.

The population of American Muslims is expected to double by 2050, from a current number of about 3.45 million. As Islam continues to grow in the United States, it builds off of centuries of deeply layered history. Losing sight of this history can negatively impact the Muslim community, according to some historians. “African Americans have lived […] under the yoke of a hegemonic presentation of Islam by postcolonial migrants to the United States,” noted Professor Aminah Beverly Al-Deen of DePaul University, another panelist at the session whose written remarks were read by Howell. She argued that African Americans whose families have been Muslims for several generations are at times treated as recent converts and “left without the opportunity to invite immigrants to the already present Islam and its contours.”

From Fort Shirley to the mosques of Detroit, Islamic history clearly has a place in the American story. The aftermath of 9/11 has seen Islam cast as more foreign and alien than ever, stated panelists. As long as drone strikes, travel bans, and extrajudicial detentions are targeted at Muslim populations, Howell remarked that Islam will be “represented as an outsider religious tradition and as an ill-fitting one at that” within the United States. Remembering parts of the nation’s Islamic past can perhaps be a remedy for this feeling of “otherness.” Panelists such as Howell argued that the feeling of being outsiders extended to African Americans within the American Muslim community.

“From my own personal experience in the Arab community, we really do forget that there are other people aside from the Arab community who are Muslims,” said Aya Beydoun, a sophomore at Wayne State University who attended the “Muslims in America” session. “The more factual history we have, the better connected we are […] the more we shape things the way we would like to remember them, the less connected and more divided we become.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Ethan Ehrenhaft is a Washington, DC, native and former AHA intern. He is currently enrolled as a sophomore at Davidson College in North Carolina and is a history major. At Davidson, Ethan serves as the co-news editor for The Davidsonian, the college’s student-run newspaper.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.