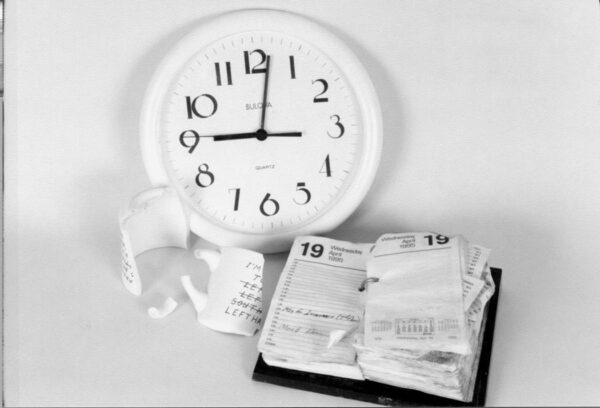

9:02 a.m., April 19, 1995

“The eyes of the world are upon us; what we do here may be a model.”1

At 9:02 a.m., April 19, 1995, the normalcy of a spring day was shattered as the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City was blown apart. Smoke covered the downtown skyline and in the days that followed the world would learn that 168 people had died in the blast. Dozens of buildings in the immediate vicinity of the Murrah Federal Building were destroyed or severely damaged. Rescue workers from throughout the state and nation aided in recovery efforts; social service agencies provided onsite assistance; and the media flooded Oklahoma City, carrying the story of the bombing to the rest of the nation and the world. Amid rubble strewn throughout the downtown area, or trapped in the debris of the still-standing Murrah Building, lay reminders of men, women, and children whose lives had been cut short by the blast. There, one could see a handbag, a toy, a coffee mug, a pink baby sweater, a desk calendar, a pair of booties, file folders, a pencil sharpener, a wall clock with its hands frozen at 9:02.

In the aftermath of the disaster, survivors, family members of victims, rescuers, and Oklahomans tried to recover some semblance of normalcy. At the same time, archivists and volunteers at the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS) and other concerned citizens realized the necessity of preserving the story of the bombing and bomb-related artifacts for posterity. Future generations would want to know everything about the terrorist attack in America’s heartland and only by gathering materials and documents now would future generations be able to know in detail what occurred in Oklahoma City.

Cards and letters of encouragement to rescuers and of condolences to family members poured into the offices of Governor Frank Keating, Mayor Ron Norick, the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, and other agencies. Local businesses affected by the bombing attempted to salvage records and other items, storing them in facilities throughout the city. The General Services Administration (GSA) provided a warehouse in an industrial area of the city for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to store, process, and investigate materials from the bombsite. But there was no central storage facility to house and process local collections of documents and items related to the bombing. Robert Blackburn, executive director of the OHS, and William Welge, director of the archives and manuscript division, set aside a small space in the OHS stacks to house local bombing collections, but space was at a premium and this could only be a short-term arrangement.

Three months after the bombing Mayor Norick convened the first organizational meeting of the Murrah Federal Building Task Force at the Civic Center.2 Ultimately, the task force would evolve into the Oklahoma City Memorial Foundation and later into the Oklahoma City National Memorial in partnership with the National Park Service.

In the early stages one aim of the task force was to appoint an archives subcommittee to identify and preserve documents and bombing artifacts for historic research, future exhibits, and a possible museum. This committee included family members and survivors, community leaders, arts council and museum representatives, and historical society professionals, all with the responsibility to draft plans for a bombing archive.

They targeted six principal areas they believed would be of “historic significance while the incident was still unfolding.” These were (and continue to be): (1) the history of the site and the immediate surrounding area; (2) details of the rescue and recovery operation; 3) response to the incident—cards, letters, and media; (4) resulting changes and/or responses to prevent or mitigate future acts of terrorism, such as glass studies, mental and physical health studies, increased security for federal buildings, and, in an attempt to prevent terrorism, gathering documents and information pertaining to the antigovernment movement; (5) investigations and trials; and (6) the memorial process.3 By October 1995, the task force approved this “blueprint of the future archives” collection and the search began in earnest to locate and preserve bomb-related documents and artifacts.

The GSA warehouse used by the ATF and FBI was made available for the bombing archives. Temporary shelving, equipment, and furniture were donated or purchased. Within the 6,000 square feet of useable warehouse space, a 2,500 square foot area was equipped with a fully climate-controlled system for the preservation of documents and artifacts.

A small volunteer staff headed by Jane Thomas, a seasoned historian, archivist, and member of the task force, set to work. Eventually, the archives itself would fall under the Oklahoma City National Memorial umbrella as a support unit for the three-part National Memorial—the Symbolic Memorial (outdoor memorial), the Memorial Center (museum and learning center), and the Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism. It was clear from the beginning the task of building the archives; aggressively collecting documents and artifacts; cleaning, cataloging, and preserving them; and interviewing key players in the incident would be a full-time job.

In April 1996 Thomas was hired as the curator of collections for the newly established Oklahoma City National Memorial Archives. She began the process of organizing the collections in accordance with the Oklahoma City National Memorial Foundation and its mission statement, and guidelines set forth by the historical society and the National Park Service’s museum standards and policies.4 In July 1996 the archives subcommittee drafted the Scope of Collections, which focused on ownership, jurisdiction, structural organization, definition, and staffing of the collections. In this early period, only a year and three months after the bombing, no one anticipated the vastness of the living, contemporary history archives operation that had been set in motion.

While Thomas had identified numerous collections around Oklahoma City and had begun retrieving and processing them, events occurred that expanded the operation significantly, such as the phenomenon of “the fence,” a chain-link fence surrounding the bombsite. Originally, the fence had been erected to restrict unauthorized access to the site, but it became the primary location for the victims’ family members and survivors to place memorials to their loved ones and coworkers. The bombsite and fence began to draw visitors from all over the nation and the world; these visitors placed their own personal memorials on the fence—ball caps, T-shirts, rosaries, flowers, key chains, stuffed toys, pictures, prayers, license plates, posters, and sacred texts of world religions.

Onsite deconstruction operations required moving and resetting the fence to protect and restrict the site’s changing configurations. Moving the fence meant removing the personal memorials. At the recommendation of advisers from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Holocaust Museum, and others, items retrieved from the fence were moved to the warehouse for cleaning, cataloging, and storing. They became a rapidly growing part of the Oklahoma City National Memorial Collections. Now, as items begin to deteriorate due to weather, they are removed for preservation, and during holidays additional space on the fence is made available for seasonal memorials.

From 1996 onward the archives aided members of the community and visitors in numerous ways. Authors writing about the bombing needed the help of the archives for accurate documentation. Filmmakers dramatized the bombing in the story Promised Land, and the archive’s staff and volunteers helped in the production. Traveling exhibits and local displays were created at the archives and outfitted with artifacts and documentation. Exhibits were sent to the Ronald Reagan Library in California, the Gerald Ford Library in Michigan, and various county courthouses in Oregon. A pilot program called “Violence Begins with Me and Ends with Me” was initiated at two local schools in an attempt to help children understand the alternatives to violence and better cope with the tragedy.

To understand the tragedy, document its aftermath, and help prevent future terrorist attacks, the archives began to gather documents relating to the radical and violent element of the antigovernment movement. While reporting on the bombing, the media uncovered the bombing suspects’ ties to this radical element, and both suspects, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, were influenced by its methods and ideology.

1997 was the year of the McVeigh and Nichols trials, both men being found guilty of the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building. Jurors were interviewed in Denver, Colorado, as were members of the prosecution and defense teams, who contributed important documents to the archives for preservation and later research purposes. The trial transcripts were obtained, processed, and labeled, and media coverage of the trials was procured, as had been the case with local, state, and national media coverage following the bombing itself.

In addition to obtaining trial materials and media coverage, documents on the memorial process itself were gathered and boxes began to mount at the archives. These contained minutes of task force and foundation meetings, agendas, bombing anniversary materials, press packets, and programs from special events such as the memorial groundbreaking in 1998. Design competition layouts were submitted by architectural teams for the symbolic memorial on the bombsite and for the restoration of the bomb-damaged Journal Record building for a memorial center, museum, and future home of the archives. These layouts, examples of the memorial process in action, line one wall in a section of the warehouse and have already become the objects of study by university professors and students of architecture. Historian Edward T. Linenthal has visited the archives often to research his forthcoming book on the Oklahoma City National Memorial. He pores over the design boards and delves into box after box of documents, in addition to interviewing family members of victims and bombing survivors.

Unlike Linenthal and the architecture students, some in the community and around the state have viewed the bombing archives as little more than “3,000 teddy bears.” In reality it is a contemporary history archive and research facility with both documents and three-dimensional artifacts. The number of documents, newspaper accounts, transcripts, interviews, books and articles, photographs, video and audiotapes, and Internet resources has grown into the hundreds of thousands.

By June 1998 approximately 20,000 artifacts and 176 linear feet of documents had been cleaned and sorted, all of which fall into the six principal categories established by the archives subcommittee in 1995. By this date the following materials had been identified as pertinent to the bombing and had been either obtained or formally requested: (1) the history of the site and surrounding area: 1–2 linear feet of documents and 50 artifacts; (2) details of the rescue and recovery operation: 40 linear feet, 500 artifacts and 6,000 photographs; (3) the response to the incident: 150 linear feet and 60,000 artifacts; (4) resulting changes and responses: 40 linear feet and 50 artifacts; (5) investigations and trials: 150 linear feet and 1,000 artifacts; and (6) the memorial process: 25 linear feet, 2,500 artifacts, and 3,000 photographs.5

The cataloging and storing processes begun in late 1995 and early 1996 are worth describing as they continue to be several of the fundamental tasks of the archive’s staff and volunteers. Documents are grouped according to kind: personal accounts, articles, interviews, reports, transcripts, speeches, government, newspapers, books, and cards and letters. A few examples of the cataloging and storing process follow.

Personal accounts, those of rescuers, victims, and survivors, are cited in files by personal circumstance, last and first names, and are filed in boxes labeled “Rescuers,” “Deceased,” or “Survivors.” Journal and other articles are cited on file folders by article/journal/date/title/ author, and are filed alphabetically in archival boxes. When full, an index list is attached to each box and the box is numbered before it is shelved. Newspapers in file folders are identified by country (if other than the United States), by state and city, and on the following line by date and the name of the newspaper. Folders are then filed in cubic foot archival boxes. Each is labeled by year and its contents recorded within. Over 130 books on the bombing and related topics are alphabetized and stored in the large metal cabinet that serves as a makeshift library. Each title and author appear in the computerized catalog. The trial transcripts are bound by date, filed chronologically by trial, and are located in cubic foot archival boxes, while audio and videocassettes receive catalog numbers; each is copied before being boxed and stored. Citations of cassettes and documents are listed in the collections index binder, a master list citing all holdings. Further, all of the documents, as well as photographs, audio and videotapes, and artifacts are entered into the computer system in a program developed by the National Park Service. It is hoped that in the near future, these resources will be listed and made available to Internet users.

Because artifacts vary greatly in size, type, and composition, they require a variety of preservation techniques, but each receives accession and catalog numbers. They are indelibly marked, cleaned, and stored, a piece of granite from the Murrah Building receiving as much attention as the most fragile china figurine.

Roll and negative numbers catalog individual photographs; they are sleeved and boxed, and browse files are being created to easily identify the 17,000 photographs collected to date without having to sort through individual boxes. A researcher exploring the story and history of the Survivor Tree, for example, can look through the browse file that contains photocopies of all the photographs taken of the tree. The browse file images identify the roll and negative numbers, and locations of the original photos. This process helps to preserve the originals and makes access to the photograph collections simple.

Photographs and other items will be used in the memorial center and museum, as they have been for past exhibits. When the new archive in the Journal Record building is completed, researchers will have greater access to the collections, a problem that presently plagues the warehouse archives because of limited space. In the new facility researchers will have their own space and assistants to help locate materials.

Until that comes to pass, however, the archive’s ongoing gathering, processing, and cataloging endeavors will continue. The archive’s staff has been working with the museum director, Sunni Mercer, and the design team to select artifacts for the museum. Providing historical information and accurate documentation is a current project; another is assisting the design team in the creation of a computerized “virtual archive.” The virtual archive will allow visitors to view artifacts in several categories and read about them at the touch of the screen. Archive staff members have provided resources for institute symposia, and have been instrumental in helping to develop the institute’s fledgling web site and library. They have photographed and documented public memorial programs and grand jury activities, and continue to interview key individuals in an attempt to record all aspects of the bombing event and its aftermath.

Ultimately the archive’s documents collection will be divided into two sections: documents on the memorial process and the bombing will fall under the purview of the memorial center and the museum; and research documents and those pertaining to terrorism will be used by the institute and its library. These changes, however, will not occur until the completion of the Journal Record building and relocation of the new facility, scheduled for the fall of 2000.

In March 1999, for the last time, the media visited the old warehouse with its rambling rooms, stacks of boxes, worktables covered with supplies, and an environment of “organized chaos.” Given the time constraints for the forthcoming move to the Journal Record building and the completion of the Oklahoma City National Memorial, staff and volunteers are beginning to prepare boxes of artifacts and documents for the move. They are beginning to disassemble shelves and “close up shop” at the warehouse. They are packing all the materials collected in the past four years, among them newspapers, trial transcripts, books, bomb-damaged Murrah Building artifacts, delicate figurines, memorials from the fence, the 9:02 clock.

Through aggressively collecting materials pertaining to the bombing and related topics, Thomas, the archive’s staff, and volunteers have begun capturing the story and preserving it for future generations in a sensitive, nondiscriminatory manner. What is gathered here and what can be learned from it may help to prevent similar acts of terrorism or, at the very least, protect innocent lives. We will learn from this model of a contemporary history archive, one which grew “out of the rubble” of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995.

Notes

- Minutes of the Murrah Federal Building Memorial Archives Subcommittee Meeting,

July 25, 1995. Special thanks go out to my colleagues, Jane Thomas, curator,

and Brad Robison, archivist, for their assistance with this article. Also special

thanks to Edward T. Linenthal for suggesting I write this article and for his

editorial comments. [↩] - Minutes of the Mayor’s Task Force for the Oklahoma City Bombing Memorial Meeting, July 1995. [↩]

- Project Summary, Grant Application, 1998. [↩]

- The Oklahoma City Memorial Foundation Mission Statement reads, “We come here to remember those who were killed, those who survived and those changed forever. May all who leave here know the impact of violence. May this Memorial offer comfort, strength, peace, hope, and serenity.” The standards included: Cultural Resources Management Guidelines of the National Park Service (NPS-28); the Authorities Act of 1906 (16 USC Sections 431–433); the Organic Act of 1916 (1 USC et seq.); the Historic Sites Act of 1935 (16 USC Sections 461–467); and the Museum Properties Act of 1955 (16 USC Section 18[f]) in the event of a partnership with the National Park Service (Scope of Collections 1996, Project Summary 1998). [↩]

- Project Summary 1998. [↩]

Carol Brown is assistant curator of the collections at the Oklahoma City National Memorial Archives.