It is a difficult time to be a historian (and student) of health care. In my Historical Foundations of Health Disparities course last spring, we spent a week focused on the medical civil rights movement. We watched footage of activists and politicians coming together for the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended discrimination in health care, and students got to watch President Lyndon B. Johnson, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. come together for the common good. The joy and pride at that signing was palpable in the recording, and the students (and I) were all visibly moved by it.

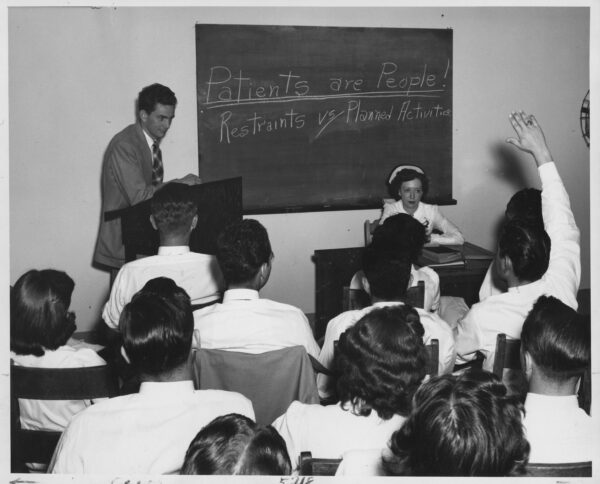

Teaching history to future health care providers gives necessary context for understanding the systems they will work in today. Menninger Foundation—Psychiatric Aides; Rockefeller Foundation records, Photographs, Series 219; Subseries 219A; Rockefeller Archive Center.

Outside my classroom, the current administration is now using that same legislation in ways contradictory to its original intended mission. These laws were meant to undo decades of discrimination in health care, but now have led to shocking health disparities between people of color and white Americans. As secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Kennedy’s son is dismantling the nondiscriminatory infrastructure of both the research and administrative arms of health care in this country, and telling lies about vaccines, psychiatry, and gender. These links between past and present illustrate how health care is always political, an important lesson that future doctors and nurses need to learn.

I came to Emory University in 2015 as the inaugural Andrew W. Mellon Faculty Fellow for Nursing and the Humanities, a new role designed to bring humanistic perspectives into health education. As I’m one of only three non-nurse PhD-prepared historians working in US schools of nursing, sharing the social context of clinical decisions and health care systems with my students is essential knowledge, and it can be both rewarding and challenging as a humanist to find ways to integrate that into already crowded curriculums. The Emory School of Nursing has recognized the importance of this work through the creation of a Center for Healthcare History and Policy, which I direct.

I teach across Emory and work with both undergraduate and graduate public health, nursing, and medical-track students. One of my core arguments to these students is that the health care system they will inherit is working exactly as it was designed. They should learn what it was meant to achieve and where it succeeded but also where it fell short. They also need to understand how it is now being torn apart, piece by piece, in ways that will affect their future careers, their future patients, and indeed even their own future health.

The health care system students will inherit is working exactly as it was designed.

To make this connection between past and present has meant moving the history of medicine beyond stories about “great” nurses or doctors. Rather, my goal is to introduce students to the vast body of work in the history of health care broadly conceived, and to situate that history in broader social processes like colonialism, slavery, capitalism, and environmental change.

To that end, my approach has always been informed by what now composes the recognized field of “applied history,” where we think carefully about what the specific lessons are that we want and need future professionals—in my case, health care providers—to take from history writ large, not just the history of their own profession. Health care students need to learn more than simply the scientific development of biomedicine. They also need to learn about the racist ideas that informed early physicians and nurses as they established their authority in the context of slavery. They need to learn how American capitalist structures shaped the impossibility of socialized health care. And they need to learn about how the New Deal and the Great Society, and ideas about these programs, shaped policy and legislation that still affect how we experience and navigate health care today.

The mission of nursing to provide holistic care to people in the context of their personal lives and social circumstances makes history particularly relevant. To do this, students need to learn a broad conception of history that explores the economic and political forces that shape their patients’ lives, as well as their own profession. One key example is the story of the first Black trained nurse in the United States, Mary Eliza Mahoney, who worked at the New England Hospital for Women and Children and graduated from their school of nursing in 1879. Mahoney’s story teaches students about the racial segregation that defined the nursing profession so long into the 20th century that Black women still make up only 25 percent of the profession. The story of Black nurses also needs to deal with the reality that they were taught the same false ideas as white nurses—that Black people were biologically different from white people. When we broaden the lens to situate nursing in the history of biomedicine, we can get closer to the origins of such disparities for patients. The goal of a history for health care approach (as opposed to the history of health care) is to enable all nurses, Black or white, to recognize the scientific racism that underpins all their practices.

I have sometimes been asked why I do not teach students more of the “good” things about American health and medicine. Scientific discoveries are important, but in a course focused on health disparities, we study how patients and communities tried to negotiate this system in order to take care of their own health when the system failed them. Here, we focus on the role of community-based health activist collectives like the Young Lords, the Black Panther Party, SisterLove, and Black midwives, along with activism focused on HIV, disability, prison and mental health reform, and Indigenous and environmental survival tactics. Students find it empowering to hear these stories of grassroots organizations and loose collectives who have fought and continue to fight for the right to health and access to care in the face of oppressive forces at the intersection of racism and capitalism.

Teaching courses like this, which involve distilling complex histories into comprehensible formats for nonhistory majors, requires a careful consideration of participation and assessment measures. How do you engage and measure students’ historical knowledge or competencies when they are not in training to be historians? Instead of paper or exams, I use activities and assessments that break down historical knowledge into digestible chunks that they can apply to current problems. To do that, I introduce them to the vast body of scholarly work, usually requiring a short reading on a topic and then providing extensive lists of supplementary materials. I ask that they read one supplementary article per week. Usually, I let them choose their own adventure, asking them to sign up for different readings so they can summarize for one another and we can pull out common themes in class.

How do you engage and measure students’ historical knowledge or competencies when they are not in training to be historians?

The final assessment is a group project. Early in the semester, we review some of the major disparities that exist in health care, and we rank them in terms of class interest. The top seven to eight categories become that semester’s group project topics. In groups of five or fewer, with guidelines for what I expect them to research (e.g., the nature of the current disparity, the historical policies that led to that problem), students design their own final project in any format that they like. Students have made video essays, podcast episodes, infographics, and virtual exhibits. The framework I’m using here is what Daniel S. Goldberg has called “historical fluency,” and the final projects live online at the Historically Informed Policy (HIP) Lab.

The key here is the phrase “historically informed.” This approach doesn’t require students to undertake original research or produce new knowledge. Rather, I ask them to take a deep dive into what’s already out there, and to synthesize that knowledge in ways that will help them, and others, in their future actions as health care providers or policymakers. In this approach, they learn about historical evidence, how the past shapes the present, and what can be learned from past practices, both good and bad.

The final project is scaffolded with smaller assignments: a group role contract that sets each individual’s contribution to the project, a work-in-progress presentation, and a peer review component. The usual issues with wrangling group projects aside, students report that they enjoy the freedom of the project approach. Many of them are taking a full load of prenursing, medical, or science classes that are heavy on rote learning and exams. In class evaluations, they report their enjoyment in the chance to be creative, to dive deeply into a specific area they are concerned with, and to have some fun with a project that builds on their group’s skills and that can be of practical use to others. They especially appreciate having their work published on the HIP Lab site.

One comment from last year sums up the general feeling about this type of course: The course lectures “opened my eyes to the historical factors and institutions that contribute to current inequities in health care. I also really enjoyed the final project and getting to dive deeper into a racial disparity of our choice. I like that we had the freedom to choose the format of the final product, and I loved hearing about everyone else’s projects during the in-class presentations.” Students report the impact long after they’ve graduated, with many telling me that in retrospect it was the most important course they took in nursing school and it should be mandatory for all students.

Does all of this work make a difference to the future of health care? Only history will tell, but these future health care providers and policymakers are at least equipped with the skills of historical fluency, and a recognition that current health care problems are a product of the past.

Kylie M. Smith is associate professor and director of the Center for Healthcare History and Policy at Emory University. She is the author of Talking Therapy: Knowledge and Power in American Psychiatric Nursing (Rutgers Univ. Press, 2020) and Jim Crow in the Asylum: Psychiatry and Civil Rights in the American South (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2026).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.