This essay is part of “What Is Scholarship Today?”

Science deeply informs my analysis of history. Yet history also crucially validates and informs science. Such symbiosis can lead to historical scholarship that provides timely warnings that hopefully inspire necessary adaptation, innovation, and survival in light of the threats that our species and planet currently face.

My scholarship is now almost always done as part of interdisciplinary teams. At its core is the nexus of history, complex systems theory, and science (particularly medicine). The heart and soul of what I study is the historical past—but recast as comparative analogy, revelatory filter, comparative prophecy, and advocacy. I came to this point in my career by relative happenstance, the how and why of it discernible only in retrospect. I graduated with a degree from Carnegie Mellon University, a school with a strong science influence across its undergraduate curriculum. My later PhD dissertation research at Michigan State University, rather unexpectedly, required me to draw heavily on that prior scientific background. I indirectly received a further interdisciplinary push from my current institution, Doane University. Faculty at our small liberal arts university are encouraged to teach broadly. We also know, grow to respect, and sometimes befriend colleagues in quite different disciplines.

In the spring of 2020, I co-taught an upper-level interdisciplinary seminar titled Apocalypse: How Societies Survive and Fail to Survive Existential Threats with physician Amanda McKinney. We had been eager to apply the holistic work of complex systems theorists and historians such as Joseph Tainter, Kyle Harper, and Ugo Bardi to current problems, which we predicted would lurk, in even more virulent forms, in the near future. (Little did we realize . . .) Teaching this particular course, as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded around the world, was a surreal experience. The class began in person and ended on Zoom. Our bridge from real-world and classroom inspiration to detailed interdisciplinary research was often initially envisioned by our curious and engaged students—in their questions and surmises.

Over time, how have humans conceptualized and wrestled with these complex challenges?

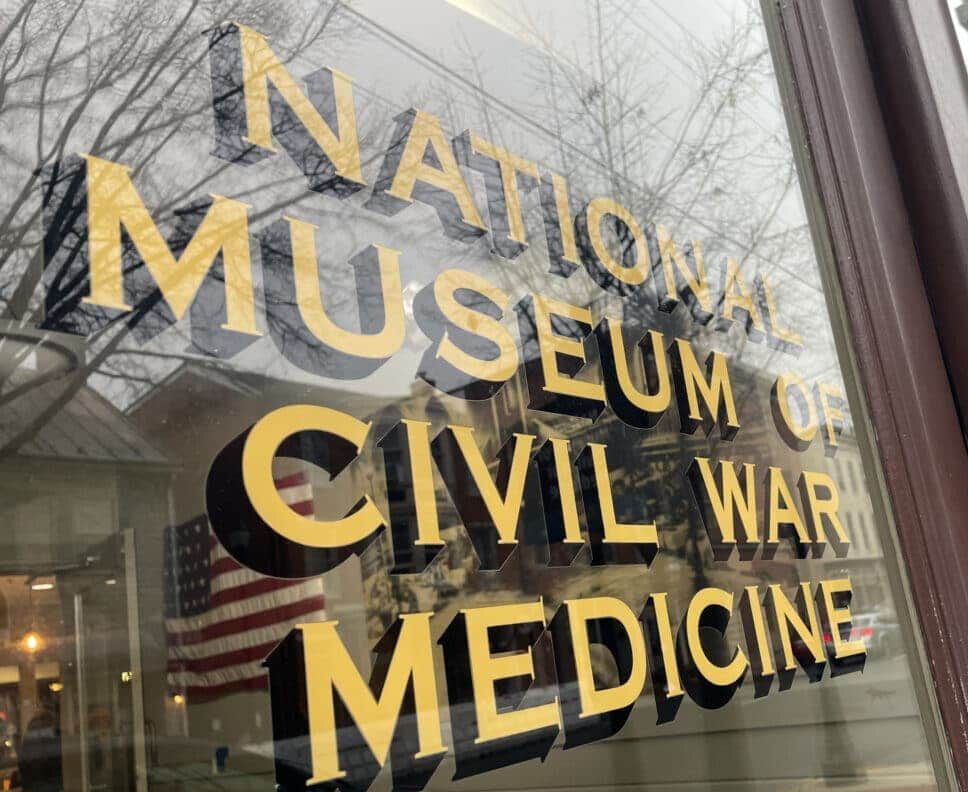

Subsequently, Amanda and I collaborated on a study of the Plague of Cyprian pandemic in the third century CE. We were joined by biologist DeeAnn M. Reeder (Bucknell Univ. and Smithsonian Inst.) in writing Interdisciplinary Insights from the Plague of Cyprian: Pathology, Epidemiology, Ecology and History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023). Using a combination of ancient and modern evidence, our team’s interdisciplinary approach alternated between analyzing ancient texts (for example, Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History and Cyprian’s “On Mortality”) and applying modern epidemiology, molecular phylogenetics, and virology. We also holistically examined the issue of pandemics and their impacts in the past, present, and (possible) future.

Later, through the lens of lifestyle medicine, Amanda and I explored intertwined issues of human and planetary health at three different stages (prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies and ancient and modern forms of civilization) related to diet, disease, and agricultural production. The resulting article and two book chapters detail potentially prophetic historical lessons regarding civilizational collapse for our 21st-century globalized planet. With this project, we have been asking multiple questions. In an era of concern about climate change, chronic and pandemic disease, environmental degradation, political and economic upheaval, and military conflict, what can we learn from past civilizations that failed to live within planetary limits? For those that collapsed, what were the broader implications? Over time, how have humans conceptualized and wrestled with these complex challenges? Our analysis leads us back (ouroboros-style) to historical lessons for our globalized planet of societal reactions to existential threats such as “the Mother of All Collapses,” as Ugo Bardi termed it: the “fall” of the interconnected Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire—a topic that was central to our 2020 course.

Our latest project, as part of a larger interdisciplinary team, is to apply some of the lessons we have learned in a way that is, essentially, prophetic. Can interdisciplinary historical scholarship regarding infectious disease outbreaks not only help elucidate the mysteries of the past but also help predict the evolution of near-future epidemic or pandemic threats against the backdrop of climate change; environmental disruption; and ever-evolving patterns of human behavior, movement, and interaction? We believe that it can. Interestingly, we will be presenting our research at a major medical, as opposed to a history, conference. For us, disciplinary boundaries continue to blur, but history loses none of its relevance or potential to inform.

Mark Orsag is professor of history at Doane University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.