I teach a history course that addresses only one element of the US Constitution: the First Amendment’s protection of speech and press. But we do not get to this very brief, hard-to-interpret late 18th-century text until about the midway point in the semester. Both before and after that moment, the class ranges around the globe and across time to introduce the idea of thinking historically—which is to say, contextually as well as philosophically—about several fundamental questions for modern democracies. Who has the right and the means to speak (and where and when and why)? What is it permissible and impermissible to say? And who or what entities get to decide on and enforce the rules?

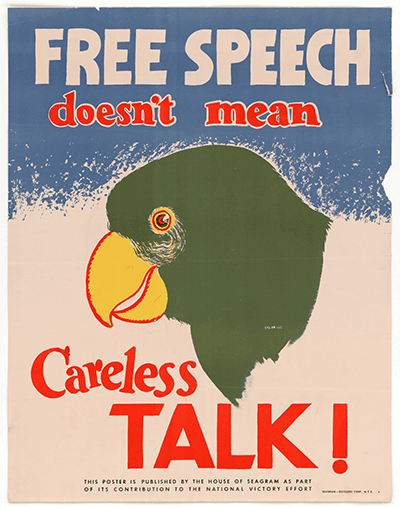

During World War II, the US Office of War Information both celebrated free speech as a characteristic of liberal democracies and warned the American public of the importance of limiting it for the sake of national security.

To that end, the course starts with several weeks devoted to arguments for the regulation of thought and expression going back to the Renaissance and the advent of printing in the West. Using case studies, including the trial of Galileo in papal Rome and the French monarchy’s efforts to stamp out a black market in dangerous ideas during the Enlightenment, the class explores varieties of intellectual coercion and official censorship (religious, political, and more), how they functioned, and, finally, the problems their agents encountered, from the way notoriety frequently drives up audience demand to the difficulty of defining standards.

Only then do we get to a new species of argument: those against censorship or, more precisely, in favor of the deregulation of speech and print. We spend the next part of the course exploring the very different grounds and circumstances on which this case was made between John Milton’s Aeropagitica in the 17th century and Alexander Meiklejohn’s Free Speech and Its Relation to Self-Government in the middle of the 20th, with considerable attention also going to key 18th-century experiments in implementing limited forms of freedom of expression prior to the US Bill of Rights. Can we really understand the particularity of various Anglo-American formulations without also considering the Swedish version of 1766, with its focus on the right to access official information or listeners’ rather than speakers’ rights? We also look at arguments, like those of early modern advocates of patent and copyright or, later, Marxists of different stripes, for new kinds of restrictions on expression. That way, the definitive but also unusually terse free speech clause of the US Constitution can be seen as the product of several centuries of intellectual, political, religious, and commercial fights and, ultimately, a radical idea on which to found and maintain a nation-state.

What happens when freedom of speech and privacy end up conflicting?

In the second half of the course, we then explore specific areas in which interpretation of the parameters of free speech remain heavily contested to this day, in part because the First Amendment and most other modern constitutional protections for freedom of expression around the world are so open-ended in their formulations. Against the backdrop of the development of capitalism, changes in information technology, the redefinition of relationships between church and state, the evolving needs of empires, the rise of the author as a profession and type, the history of slavery and abolition, the development of new conceptions of art, the invention of an international order along with the expansion of warfare, and more, we address enduring and tough questions. What counts as seditious speech? What is blasphemy and why have charges of it lasted in much of the world? What happens when freedom of speech and privacy end up conflicting? What is obscenity and how can we tell it apart from art or literature? Where does the idea of “hate speech” originate and what, if anything, should be done to curtail it? When should freedom of speech extend to lying and falsehood and when should it not?

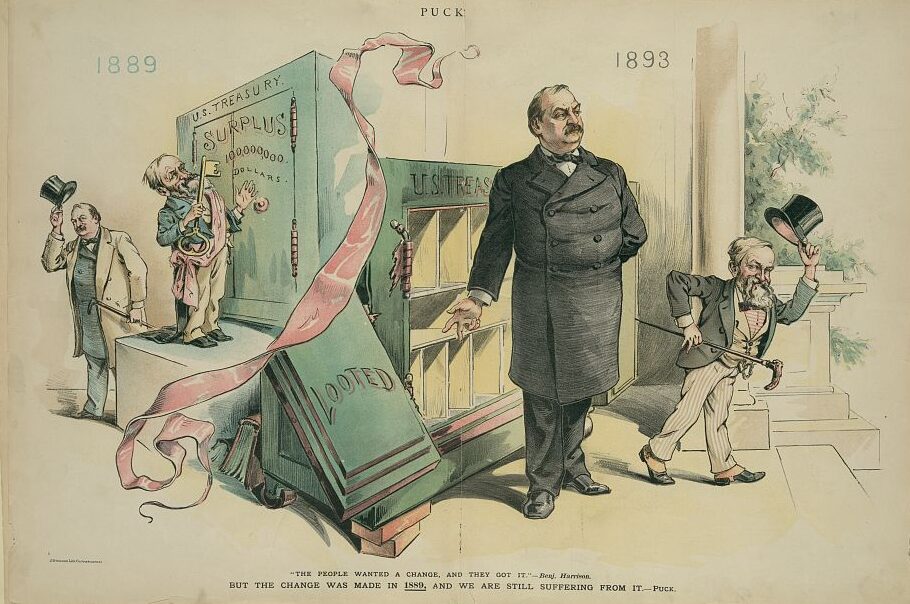

Test cases for this part of the course range from fights over the Alien and Sedition Acts almost immediately after the introduction of the First Amendment in the 1790s to very recent and ongoing conflicts in multiethnic Denmark and France around the making and showing of cartoons depicting the prophet Mohammed. We also consider what counts (and when and where and by whom) as expressive, from clothing to money; how the spaces where expression happens, from schools and universities to village squares and parks, shape perceptions; the challenges wrought by the internet and artificial intelligence; and how speech rights and power intersect in an inegalitarian world.

Every time I teach this course—and over the last 14 years, I’ve taught variants at the University of Virginia, Yale University, and the University of Pennsylvania—I need to update the syllabus. Much of the reading is centuries old: Inquisition trial records, Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s underground vision of a communicative utopia, guidelines for speech in British India. But as the contemporary issues keep changing, the examples and the readings need to change as well. Every semester, we also try to track newsworthy speech-related developments unfolding in real time, from the legal fortunes of cake bakers who don’t want to be compelled to produce “creative” work in support of gay marriage (Masterpiece Cake Shop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission) to arguments about Chinese technology transfer policy. The goal is to explore these examples in a larger historical framework, not just to approach them as normative problems to be solved at a philosophical level, though we do some of that as well.

But this past year, as the Israel–Hamas War escalated and produced protests and counterprotests on many US college campuses, including my own, it sometimes felt as if the news cycle was moving faster than we could keep up—and it was all hitting a little too close to home. That’s also when I did some new thinking about how much and how best to incorporate this very raw conflict into the course. I decided that rather than shy away from the controversy, we could approach it together as yet another historical dilemma. The great thing, after all, about a history class that explores a single aspect of the US Constitution from so many angles is that it gives students (and, in truth, the professor too) new tools with which to analyze their own reality and come to truly thought-out points of view. How would a follower of John Stuart Mill—or for that matter, Frederick Douglass or Emma Goldman or even Herbert Marcuse—respond to what’s unfolding around us right now? Is the First Amendment still (or has it ever been) up to the task of helping us practice democracy or arrive at truth, or is it getting in the way? Is the tradition of free speech as laid out in the Constitution suitable to or in need of modification in the classroom and the larger university itself? How does it fit, or not, with notions of academic freedom but also the basic mission of higher education and its promise of equal terms on which to learn for all?

As the contemporary issues keep changing, the examples and the readings need to change as well.

All these questions came up in my fall 2023 class. The responses never divided along standard political right/left axes—free speech questions generally don’t. What was so valuable was the opportunity to hear a classroom full of young people characterized by differences in place of origin, background, political leanings, and areas of study and interest wrestle with how a constitutional democracy should work by considering how it has—and considering the promises and pitfalls of the alternatives.

Sophia Rosenfeld is Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History and department chair at the University of Pennsylvania. Her forthcoming book is The Age of Choice: A History of Freedom in Modern Life.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.