When the current coalition government came into being in January 1993, the National Archives of Ireland was transferred from the Department of the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) to the new Department of Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking areas). Dr. David Craig, the director of the National Archives, said that all functions have been transferred to the new minister of the Department of Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht with the exception of functions relating to the retention of records by departments. The Taoiseach still retains the power to prevent government departments from withholding relevant records from the National Archives, but in general it is unlikely that departments would seek to withhold such records. In fact, the National Archives has benefited greatly from a massive influx of departmental records.

The National Archives owes its existence to the Department of the Taoiseach. In 1985, the Taoiseach Dr. Garret Fitzgerald was responsible for the introduction of the National Archives Bill, whereby the former Public Record Office and the former State Paper Office were amalgamated to form the National Archives. Three years later, Charles Haughey, who succeeded Dr. Fitzgerald as Taoiseach, brought the National Archives Act into full operation and so ensured that government records which were more than thirty years old must in general be handed over to the National Archives by January 1991. To expedite matters under the thirty-year rule, the administrative burden for the transferal of all records was placed onto government departments and not the National Archives.

At the time of the amalgamation of the two former facilities in 1988, the National Archives had about eighty thousand cubic feet of records. In the last four years, however, the institution has obtained an additional forty thousand cubic feet of records. While most of these newly acquired records are departmental records, some are private records of various kinds and of much significance. It is now clear that the National Archives possesses a storehouse of rich materials for the benefit of historians, teachers, students at all levels, journalists, government officials, lawyers, professional genealogists, and the wider public.

It is estimated that the National Archives now holds the equivalent of about 180 thousand boxes, and as each box has a capacity of about 0.67 cubic feet, the total holdings amount to approximately 120 thousand cubic feet. This is roughly the same quantity of records that were destroyed in the disastrous fire at the Four Courts in 1922. However, by the time the National Archives Act of 1988 has been fully implemented, and the institution obtains and clears all the records up to the thirty-year rule, it is estimated that it will have increased its holdings to 200 thousand cubic feet. While these estimates are rough, they have placed great demands on the director and staff at the National Archives.

To facilitate the National Archives in its mission, the government allocated new premises at Bishop Street in Dublin to the archives in October 1989. The premises were reconstructed to store large quantities of paper for the Government Supplies Agency (GSA) between 1983 and 1986. In reality, this decision represented a compromise as some observers had pressed the Taoiseach to allocate funds for a new building designed solely for the National Archives. Since then, one of the first objectives of the National Archives has been to transfer all their mainly textual records to the premises on Bishop Street. A second objective has been to establish facilities needed to provide good services to the public.

At present, most of the Bishop Street building is still occupied by the GSA, and until such time as the GSA vacates the premises, the National Archives cannot fully satisfy its objectives. The National Archives must continue to store part of its growing mountain of records at two other locations, the former Public Record Office at the Four Courts building and a facility in Upper Dominick Street. By modern archival standards, both facilities have serious shortcomings, and thus it is hoped that all the records at Dominick Street would be transferred to Bishop Street by the end of 1993, and that the records at the Four Courts would be transferred by the mid to late 1990s.

If all goes according to plan, the Bishop Street premises should eventually provide the National Archives with over 150 thousand square feet of floor space, of which a considerable part is conveniently fitted with shelving suitable for archival storage. More than half of the storage space, however, consists of a warehouse at the rear of the Bishop Street building. At present, the GSA operates a pallet and forklift system within the warehouse by which to retrieve supplies of paper and other materials. When the GSA finally vacates the warehouse, the National Archives intends to build a new structure within it, as the current pallet and forklift system is not appropriate for the retrieval of individual archive boxes. At that time, the National Archives would need the close cooperation of the Department of Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht as the adaptation of the warehouse will require additional funding.

To provide access to the records, the National Archives has established a new sixty-eight-seat reading room on the fifth floor of the Bishop Street premises for the benefit of the public. Readers may recall that the reading room at the State Paper Office in Dublin Castle was closed in December 1990, and the reading room at the Four Courts was closed in August 1991. Major alterations were necessary to make the fifth floor of the Bishop Street premises amenable to the public, and more work is still in the planning stages. The absence of a cafeteria for the public (the staff enjoy a small canteen on the sixth floor) may be rectified when the GSA vacates the ground floor, which could be fitted out with a self-service catering area, a public lecture room, and an exhibition room. These plans, however, are still being formulated. Having scarce resources, the National Archives has no immediate plans to establish a computerized system in the reading room.

Members of the public have shown their appreciation for the new reading room at Bishop Street as the number of those who inspect the archives on a daily basis has increased dramatically. In June 1990, it was estimated that thirty members of the public inspected documents at the National Archives on a daily basis. The most recent estimates indicate that an average of sixty members of the public inspect the archives on a daily basis, which represents an increase of about 100 percent over a three-year period. The reading room is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, excluding bank holidays. Documents are produced to researchers between 10 a.m. and 12:45 p.m., and between 2 p.m. and 4:30 p.m.

When one considers the increased popularity of the new reading room, four points must be kept in mind. First, the closure of the Four Courts relieved the public of a small and badly designed facility. Second, the closure of the reading room at the State Paper Office in Dublin Castle was also a major benefit, as it was hopelessly inappropriate as a place for storage. (In June 1986 a serious accident took place in the Record Tower of the State Paper Office, when a member of the staff fell from a ladder while taking down a box that weighed some fifteen pounds. This resulted in a ban on access to documents stored at a level of more than eight feet off the ground. The eight-foot rule affected some of the best series of papers, including the Chief Secretary’s papers, which made some academic research for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries impossible.) Third, the new reading room was a great improvement on its predecessors. Fourth, the transfer of the departmental records under the thirty-year rule increased the holdings of the National Archives substantially.

To cope with the influx of records and researchers, the National Archives employs about thirty staff members, including four full-time archivists and one part-time archivist, not counting the director and the senior archivist. To increase productivity, computer terminals for over half the staff were installed in 1991, and more ambitious plans for their use are currently under discussion. At present, the starting salary of an archivist is between 13,000 and 14,000 pounds per year, which rises in fourteen annual increments to 23,500 pounds. During the 1980s, severe restrictions were placed on the recruitment of staff to the entire civil service. Indeed, a hiring embargo was in force between 1987 and 1989, and the number of staff employed by the National Archives fell during that period. Even though more staff, both service and archivist, are desperately needed to clear the backlog of material, the staffing levels at the National Archives have not completely recovered to the levels in the early 1980s.

For researchers unfamiliar with the holdings of the National Archives, in principle all aspects of Irish nineteenth- and twentieth-century history may be explored profitably. At the same time, the National Archives has a particular strength in Irish political, administrative, and social history. More specifically, recent scholarship has tended to concentrate on Irish foreign affairs, and it is thought that a number of significant works in this area are being prepared for imminent publication.

A surprising amount of research has also focused on the papers of some of the less important government departments, such as those of the former Department of Posts and Telegraphs, which went out of existence in 1979. These papers hark back to a bureaucratic era when civil servants operated the postal, telegraph, and broadcasting services. In contrast, not as much research as might have been expected has focused on the records of agriculture and the records of industry and commerce, which arrived later than the others. While both sets of records are somewhat disappointing, they are quite voluminous, suggesting that Irish economic history is less popular than social and cultural history.

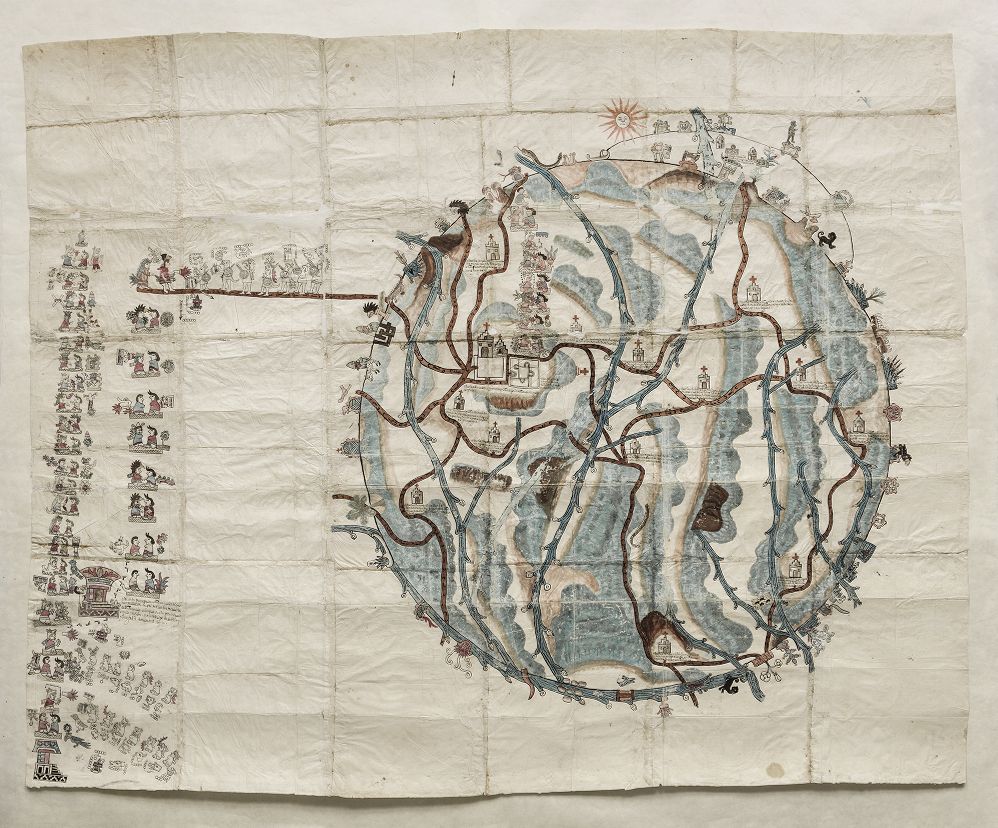

Last but not least are the records of the Ordnance Survey (national mapping agency), which are only now being released to the public. These records are particularly noteworthy as British mapping techniques were developed on Irish soil in the nineteenth century. A massive amount of supplementary material was generated in the preparation of maps. While most of the maps themselves have already been published, the accompanying manuscripts have not been seen before. They would be excellent sources for cartographers, geographers, and historians with an interest in the nineteenth century. In sum, the National Archives has more than amply fulfilled its duty both to the government departments in preserving their records and to the public in making the archives accessible.

Brian Henry is a department associate in the Department of History at Northwestern University.