The latest data from the federal government on the number of bachelor’s degrees in history awarded in academic year 2011–12 can be sliced many different ways, and the result is a mix of good news and bad.1

The discipline added a very small number of BA graduates, almost making up for the small number lost the year before. The bad news is that the history BA’s market share—the percentage of all bachelor’s degrees that are history degrees—declined for the fifth year in a row. The good news is that smaller institutions geared toward teaching continued a positive trend and graduated more history BAs. The bad news is that the traditional core of the history major—institutions with intensive research activity—continued to lose history students. The discipline’s undergraduates are slightly more diverse, but only one clearly identifiable ethnic group is driving this diversity.

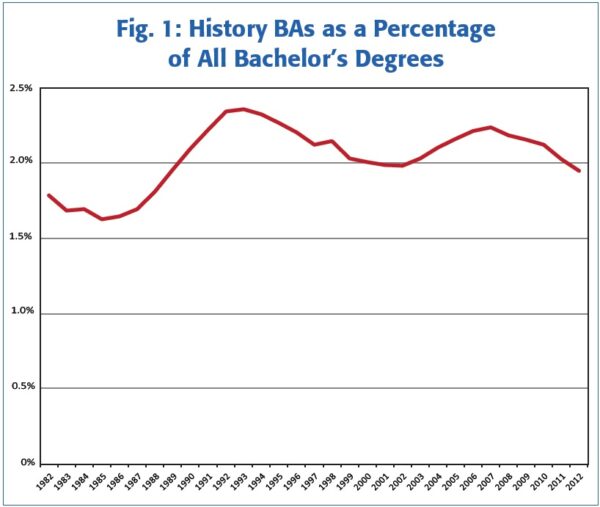

History departments graduated 150 more history BAs in 2011–12 than in the previous academic year. This comes after a loss of 230 students (from 2009–10 to 2010–11). But since the overall number of bachelor’s degrees went up at a higher rate, the total number of history BAs for this latest year (35,337) is only 1.95 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded in 2011–12. This is the first time since 2002 that history’s share of US bachelor’s degrees has slipped below 2 percent.2 The last time the discipline’s share was above 2.5 percent was 1977, so even though the discipline has grown, in one respect, it has not grown as fast as the undergraduate population as a whole, and appears to be stuck providing somewhere between 1.5 and 2.5 percent of all the bachelor’s degrees awarded (fig. 1).

Figure 1

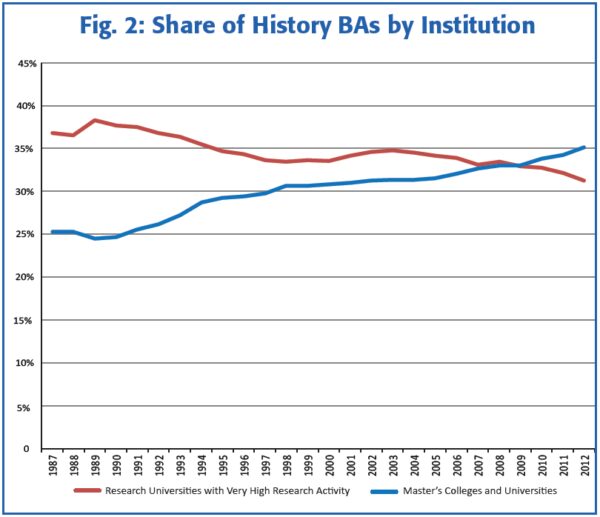

Contributing to this stagnation is the fact that fewer and fewer undergraduates at intensive research universities are taking the history major. This is not news to regular readers of this magazine, but the latest data more firmly establish this as a trend.3 Research universities with “very high” research activity (as determined by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; we sometimes still refer to these institutions as “R-1s”) graduated 11,045 history BAs in 2011–12. That’s fewer than they graduated in 2005–06. And while in 1989 these institutions accounted for 38 percent of all history BAs, they now account for 31 percent. Since their share of all bachelor’s degrees slipped by only 3 percent during the same time period, it’s difficult to attribute the change in history degrees entirely to a general shift from large universities to smaller institutions.

There are only 108 institutions listed in this category (for a full list see bit.ly/MpJKGy). They have big history departments and account for a significant number of tenure-track jobs available to history doctorates. These departments have long provided the bulk of history BAs, but they now appear to be in the midst of their first multiyear decline since 1993.

Other Carnegie groupings of institutions—those that have “high” levels of research activity, those that have little research activity but do have large PhD programs, and the baccalaureate colleges—have had flat levels of history BAs for some time. But the group classified as “master’s colleges and universities” (for examples see bit.ly/1edQLE1, bit.ly/1edQO2A, and bit.ly/1edQT6r), which includes institutions that award at least 50 master’s degrees (in all disciplines combined) but fewer than 20 doctorates, has been graduating more history BAs every year, even during years of overall decline. In 2009, Department of Education data had, for the first time, master’s institutions surpassing institutions with very high research activity in terms of number of history BAs conferred. Since then, the gap has only widened as the master’s institutions continue to add history majors, both in terms of totals and in terms of the percentage of all history BAs, and the institutions with very high research activity continue to lose them (fig. 2).4

Figure 2

This shift, if it continues, has discipline-wide implications—in terms of teaching, job prospects for PhDs, and research output—that have likely not yet been felt. But in terms of the overall health of the history major, we should ask ourselves why the large research-oriented institutions are losing history majors and what can be done to reverse this trend, and what can be done to nurture and build upon the growth in institutions that are succeeding in attracting more history students. What are these institutions doing right, and can it be duplicated?

While the growth of interest in history in these institutions is encouraging and promising, it has the potential of soon running up against a long-standing issue—namely, the discipline’s mixed record in attracting women and minorities. The latest numbers are hardly more encouraging than the ones that have come before. The share of history BAs going to women (40 percent in 2011–12) is hardly a great improvement over the share in 1995 (38 percent) and is even slightly down from 2006 (42 percent). Meanwhile, women are receiving 57 percent of all bachelor’s degrees—and 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded by master’s institutions (table 1).

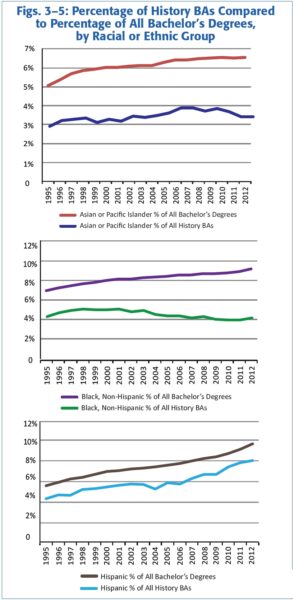

And while every large racial and ethnic group tracked by the Department of Education has steadily increased its share of bachelor’s degrees awarded, when it comes to the history BA, the record is inconsistent. Fewer Asian students took history BAs in 2011–12 than in any of the academic years from 2005–06 to 2009–10. There are slightly more African American students earning history BAs than there were 20 years ago, but they claim a lower percentage of all history BAs. The proportion of these students in history departments went up during the late 1990s and then back down. In 1995, this group received 4.7 percent of all history BAs and 7.3 percent of all bachelor’s degrees. In 2011–12, they received 4.5 percent of all the history BAs, and 9.5 percent of all bachelor’s degrees (figs. 3 and 4).

Table 1. Proportion of Degrees Earned by Women

| % of History BAs | % of Bachelor’s Degrees | |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 38% | 55% |

| 1996 | 39% | 55% |

| 1997 | 38% | 56% |

| 1998 | 39% | 56% |

| 1999 | 40% | 57% |

| 2000 | 41% | 57% |

| 2001 | 41% | 57% |

| 2002 | 41% | 58% |

| 2003 | 42% | 58% |

| 2004 | 42% | 58% |

| 2005 | 41% | 58% |

| 2006 | 42% | 58% |

| 2007 | 41% | 57% |

| 2008 | 41% | 57% |

| 2009 | 41% | 57% |

| 2010 | 41% | 57% |

| 2011 | 41% | 57% |

| 2012 | 40% | 57% |

Whatever small improvements have taken place in terms of minority representation among history majors has been due to a steady increase in the participation of Hispanic students (and a steady growth among the nebulous population identified by the Department of Education as “other/unknown”).5 The number of Hispanic students earning a history BA has more than doubled since 1995 (to 2,867), and the share of history degrees earned by this group has gone up as well. Even in 2010–11, when the overall number of history BAs went down, the number of history BAs awarded to Hispanic students went up (fig. 5).

Figures 3-5

The numbers behind these percentages, like those of other groups, are very small compared to white students, who received 75 percent of all the history BAs in 2011–12. But the trends are still discernible. Between academic years 1995 and 2012, the number of history BAs awarded to white students increased by a factor of 1.2, while those awarded to Hispanic students increased by a factor of 2.4. At the master’s institutions, the number of history BAs awarded to Hispanic students increased threefold.

In sum, there is little growth in the total number of history BAs, a decline in history’s share of bachelor’s degrees, and a suggestion of overall stagnation over the past few decades. Behind this are two areas of dynamic growth—in master’s institutions and among the United States’ fastest growing ethnic group—that are encouraging but may be hard to sustain.

Still, the fact that there are areas of dynamic growth shows that declining or stagnant interest in the history BA is not at all universal, and that there likely exist models for growth and ways to frame or reform the history major that will increase its appeal across institution types and across demographic groups. The data, unfortunately, only suggest where we might look and what kinds of conversations we might have.

Notes

- Data in this article are derived from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) Completions Survey, and the IPEDS Completion Survey by Race, accessed through the WebCASPAR database on January 27–28, 2014. [↩]

- This does not include BAs in history earned as a second major. The Department of Education presents these graduates in a separate data set, making comparisons (especially those that compare the history BA to the bachelor’s degree in general) very difficult. [↩]

- See Robert Townsend’s articles on this data set in April 2013 and February 2014. [↩]

- This shift is not likely due to a larger shift in the bachelor’s degree in general—master’s institutions, as a group, have long awarded more bachelor’s degrees overall than universities with very high research activity. [↩]

- The data set discussed in this article relies on a standardization of categories that includes Latinos as “Hispanic”; for the sake of accuracy, we will use this term here. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.