Romain Gary’s statement “There’s nothing gloomier than an organization” elegantly captures my feelings about taking attendance. Albeit necessary and even required by college policy, it can be a grim way to start a class. The ritual reminds me of middle school, or a penitentiary, in the way that it suggests to students a reward, or the absence of a punishment, for simply showing up to class. Considering the financial and personal sacrifices that students and their families often make to attend college, it seems surprising that professors need to do a head count before each class begins. I confess that when I started teaching, I was surprised to learn that I even needed to take attendance.

To be fair, I was chronically late to class when I was a student (I confess this to my students on a regular basis). Moreover, I cannot help but wonder whether the relative freedom students experience after the very authoritarian approach of many public high schools may cause students to lose sight of their agency in “getting” an education. Certainly, most students don’t need compulsion to show up to class, but for the less motivated, I do not doubt that required attendance is beneficial. Regardless of how one interprets or makes sense of students not showing up to class, it is a fact of our professional lives.

The Rebuke of Adam and Eve (1629) by Domenichino. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Patron’s Permanent Fund.

A few years ago I began to experiment, in modest ways, with new approaches to attendance. As I called each name I would ask the student a question. To a long-haired man in a T-shirt I asked: “Do you really like Led Zeppelin, or is the T-shirt an effort at irony?” In the conversation that followed, I learned that he was a local kid who was not only in a rock band but helped run the family goat-cheese operation and was an honors English student. Similarly, questions such as “Where were you last class?” “How did you break your hand?” and “Who are you texting?” helped me to quickly begin to engage with individual students, and made it easier to put faces, names, and personalities together more quickly.

Since then, I have continued to experiment with such “attendance practices” in the hope of accelerating the development of cohesive and comfortable learning communities. My goal is to break down the kinds of barriers between teacher and student, including the ever-expanding generation gap, that often impede productive communication.

I also began to wonder if there was a way to incorporate class content into the attendance procedure. While teaching World Civilization I, I asked myself what the ancients would have done with, or to, the student who ditched class. The ancient sages certainly wouldn’t have marked them absent and moved on. No, the student would have endured some sort of tongue-lashing, at a minimum. In Rome, the student’s slave would have been vigorously punished. Could such a practice help students become more interested in ancient texts? Could one develop attendance practices that correspond to the class material? I began to issue historically relevant rebukes to students who missed class, although these were not written in stone, nor in the syllabus.

After I had learned the students’ names, I would take some time during each class to issue a rebuke to the missing students. If possible, I would invoke a text from the day’s lessons to give the rebuke some theological or juridical heft. The Judgments of Hammurabi, Deuteronomy, and the Confucian texts all provided excellent approaches to bringing the wayward individual back into the fold of state, society, and my 100-level course. What student will forget “to set up respect, it is for you to respect your elders?” Will the disobedient or rebellious student not think twice about skipping after he or she hears that “if that man has wisdom, and desires to keep his land in order, he will heed the words which are written upon my pillar?”

Upon the prodigal’s return to the fold, I would do a short follow-up rebuke, sometimes sharing with the student the text that I had invoked to announce that he had gone AWOL. It was also a handy and quick way to review the previous class session material. Of course, I also made a point of e-mailing the student in question. If there was a serious reason for the absence, I did not invoke the face-to-face rebuke.

In an effort to emulate the efforts of ancient states to monitor their subjects, I also let students know that if they skipped class, they were subject to rebuke anywhere and anytime. No one who dared miss my class was safe. I once passed a fugitive student, who had missed class that morning, sitting at the window of a restaurant on what seemed to be a date. The student and his companion were staring into each other’s eyes. I rapped on the glass until the spell of love was broken and, once I had his attention, wagged a finger at him.

The rebuke approach began to work well, judging from rising attendance. Better yet, students came up before class to let me know they understood that they had been rebuked, that they were deeply sorry, and that they would try harder to not miss class again. Sometimes they wanted details of the rebuke and expressed regret for missing the performance. This suggested to me that students had come to see my pompous announcements as part of the culture of the class. And, all the better, the rebuke offered a way to reflect on the class content in pedagogically creative ways.

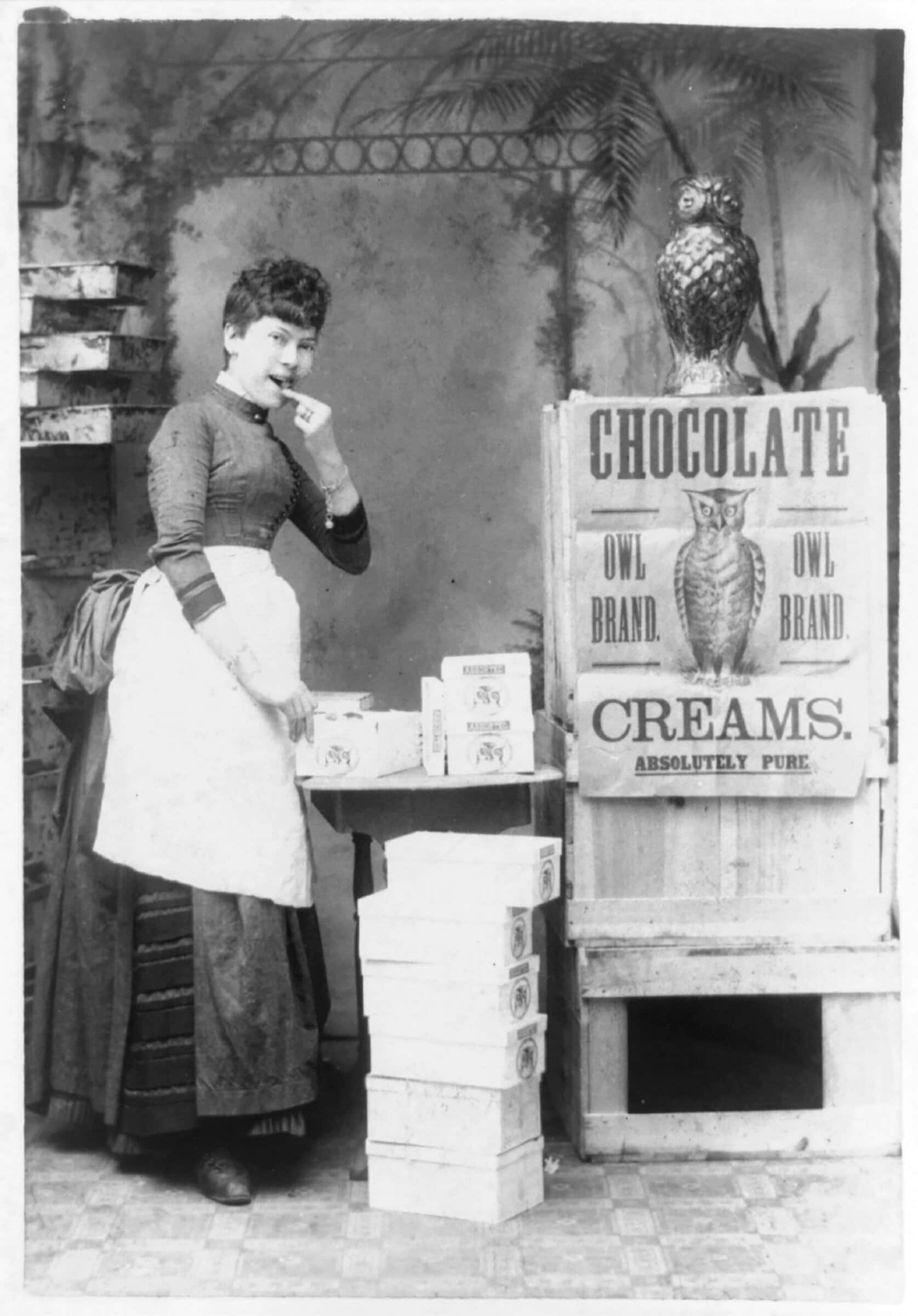

Last fall, I taught two sections of a course on the history of commodities. Since the course focused heavily on consumable substances, I imposed a tribute on students who skipped class. Like the rebuke, tribute quickly was incorporated into the rhythm and culture of the class. Students looked forward to seeing what tribute would be distributed, and if it was edible. When Capri Suns were offered two days running, the students voted to ban the substance due to its unsustainable packaging. When a student brought pecans from her family farm in Georgia, we discussed the economic challenges of producing on a small scale in a saturated market.

Along with the simulated punitive approach, I talk with students about the value for themselves and for the class more generally of consistent attendance. I’ve yet to find a better way to deliver the message that their presence matters than “Did I Miss Anything?” by Tom Wayman. I always get laughs when I announce on the first day of the semester that the syllabus contains an attendance poem. As I read Wayman’s free verse poem to them, the chuckles die out, the students begin to pay attention, and their nods and looks confirm to me that they understand Wayman’s fundamental message.

Part of the joy of the classroom is the sense of the collective that often emerges as students and teachers form bonds around the shared experiences of learning, and the struggles that sometimes arise with it. The nontraditional roll call can provide moments when teacher and student can get to know each other, have a laugh, and reinforce course material in more informal ways. And a little levity, especially being able to laugh at oneself, offers a useful antidote to many students’ fear of failure and their stress at encountering new material and the new experience of college itself.

Jonathan Ablard is an associate professor of history and codirector of Latin American Studies at Ithaca College. His current research projects include a study of obligatory military service in Argentina and a history of the nutrition transition in Mexico and the Circum-Caribbean. He is the author of Madness in Buenos Aires: Patients, Psychiatrists, and the Argentine State, 1880–1983 (Ohio University Press and University of Calgary Press, 2008).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.