The September 2025 issue of the American Historical Review features articles on Korean diasporic atomic bomb survivors, Jamaican activists and socialist internationalism, and naturalized citizens in 19th-century China. The History Lab features a special edition of History Unclassified—“Mistakes I Have Made”—and an #AHRSyllabus module on the history of higher education.

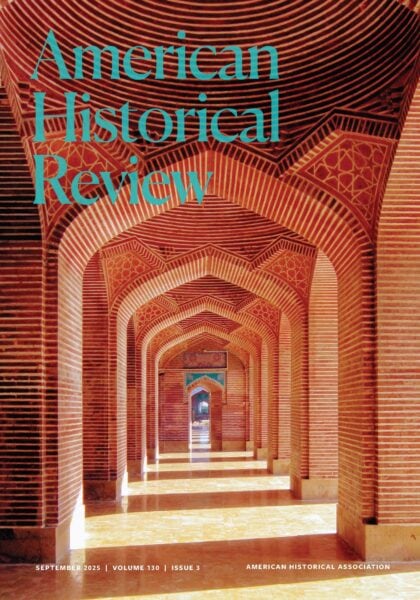

This issue’s cover features an image from Taymiya R. Zaman’s “Cities, Time, and the Backward Glance” (June 2018), the very first History Unclassified essay. In her essay, Zaman expressed unease with the historical discipline’s reliance on a linear sense of time and an assumed, unwavering authorial voice. The photo depicts a 17th-century Mughal mosque in Thatta, Pakistan. In her description of the archways, Zaman wrote, “I walk back across the courtyard, to where I can see arches in a row, and through each arch I see another arch, until I am pulled into an infinity of arches that stretch into the distance and then narrow to a luminous doorway, beyond which the eye cannot see, and language fails.” Photo by Taymiya R. Zaman.

The issue opens with Naoko Wake (Michigan State Univ.) and Michael R. Jin’s (Univ. of Illinois Chicago) article, “Surviving the Bomb in Diaspora.” Wake and Jin examine the experiences of Korean diasporic atomic bomb survivors (pihaeja) who have been deprived of their national right of redress. They argue that the dominant liberation narrative that the atomic bombs delivered Koreans from Japanese imperialism has obscured the continuing hardships of survivors across colonial, national, ethnic, and diasporic boundaries. Survivors’ struggles against US-centric notions of compensatory justice highlight the fundamental limits of the postcolonial discourse on human rights, and offers a critique of the dualistic notion of the war being between Japan and the United States that persists in the bomb’s historiography.

In “Unpaid Debts,” Giuliana Chamedes (Univ. of Wisconsin–Madison) provides a novel account of the New International Economic Order (NIEO) from 1974 to 1980, arguing that its failure resulted in part because of the limits of socialist internationalism. Chamedes specifically looks at Jamaican activists and their efforts to redefine “socialism” and “socialist internationalism” on national, regional, and global scales to build support for the NIEO and global wealth redistribution. Centering this struggle and the difficulty of trying to overcome imperial and Cold War logics, Chamedes argues, sheds new light on the world-making visions of the 1970s and their unexpected, enduring afterlives.

Nicholas McGee (Durham Univ.), in “To Change in China,” explores cases of Americans and Europeans who attempted to become naturalized subjects in late 19th-century Qing China. McGee argues that little is known about China’s place in the global debates on naturalization because of deliberate erasure efforts by Euro-American powers to deny the legitimacy of white naturalization in China. These powers feared that such naturalizations threatened the broader racial hierarchies they were constructing in Asia. McGee reconstructs and contextualizes these naturalization cases to expand the story of modern nationality in China, and to reinsert China into a global history with present-day implications.

This issue’s History Lab features a special edition of History Unclassified. The History Unclassified section is “devoted to creative, unconventional, genre-bending modes of historical writing,” and in this special edition, “Mistakes I Have Made,” consulting editors Kate Brown (Massachusetts Inst. of Technology) and Emily Callaci (Univ. of Wisconsin–Madison) invited historians to “reflect on their missteps and how they reveal insights into historical practice.” As they reflect on the trajectory of History Unclassified, now in its seventh year, Brown and Callaci ask, “What if the imperfect human historian—with their flaws, their biases, their long-entrenched assumptions—is actually the best tool of historical exploration?”

This special edition features six essays. In “Mistakes I Carried,” Conor Heffernan (Ulster Univ.) explains how after writing a history of bodybuilding in the 20th century, he realized he had left out a crucial source of knowledge: his own body. An avid bodybuilder, in his teens he had subjected his body to a punishing regime in a pursuit to overcome gendered and racial anxieties during an economic crisis in Ireland. He used that insight as a lens into larger historical processes of capitalism, white supremacy, and masculinity.

In “Whose Revolution?” Lisa Covert (Coll. of Charleston) writes about traveling to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, to write a dissertation about revolutionaries in the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). A conversation with Genaro Almanza Ríos, who had taken part in what she and other historians consider the counterrevolution that followed in the late 1920s and 1930s, led her to understand that “instead of framing San Miguel de Allende as a place left behind in the wake of revolutionary progress,” she might “see it as a place caught between two different ways of imagining the future.”

Claire D. Clark (Univ. of Kentucky) names her mistake as one of misrecognition of the historical subject in “The Battles over Addiction Treatment.” In her book about the controversial drug addiction treatment group Synanon, she had chosen not to include a passage about the well-known and sensational disbanding of the group, when some members planted a rattlesnake in a crusading lawyer’s mailbox. Angry with the omission, the lawyer made a public attempt to discredit Clark that sent her tumbling into a revival of depression and addictive behavior, leading her to question the nature of recovery programs that she had once trusted. Her experience guided her to develop a new research program, rooted in an ethics of care and healing.

This issue’s History Lab features a special edition of History Unclassified.

Trauma and care are similarly at the heart of Marius Kothor’s (Harvard Univ.) essay, “The Rooster Says There Is Life in Fear.” Kothor, a child refugee from Togo, at first carefully ended her history of women textile traders in 1963 to avoid the violence of the Eyadéma presidency that began that year. She did so to skirt the trauma of her own flight from Togo as a child. When she came to see this mistake, she started to better understand the hesitancy she encountered when conducting oral history interviews, and it led her to innovate a new ethos and practice of care in her methodology.

Mistakes and the desire to avoid them occur not just in the research process but in our professional lives as a whole. In a graphic essay called “Embracing the Untamed Garden,” the mother-daughter team of historian Claire Schen (Univ. at Buffalo, SUNY) and artist Maddy Cherr explore the mistake of attuning one’s career to productivity metrics that aim toward perfection. In “Slipping from the Podium,” Michael Kugler (Northwestern Coll.), Kelli Y. Nakamura (Kapi‘olani Community Coll.), and Julie Rancilio (Kapi‘olani Community Coll.)—all first-generation academics—reflect on their mistake: impersonating the expertise and the seemingly omniscient knowledge of their college professors at elite universities, rather than connecting with the goals of their own first-generation students in the small colleges where they teach.

This special edition ends where History Unclassified began. In 2017, Brown submitted her play The Chernobyl Crucible in Two Acts to the AHR. It was ultimately rejected for publication, but it started a conversation with then–AHR editor Alex Lichtenstein about creating a space in the journal that encourages authors to think differently about the forms history can take. Ultimately, this led to the launch of the History Unclassified section in the June 2018 issue. This special edition finishes with inclusion of Brown’s original script submission.

The History Lab concludes with the latest #AHRSyllabus module. Kelly Schrum (George Mason Univ.), Nate Sleeter (George Mason Univ.), Kevin J. Bazner (Texas A&M Univ.–Corpus Christi), D. Chase J. Catalano (Virgina Tech), Roman Christiaens (Univ. of Arizona), Erin E. Doran (Univ. of Texas at El Paso), Katie N. Smith (Temple Univ.), and Mary Kate Steinbeck (Univ. of Georgia) introduce the use of college and university digital archives to capture the rich histories of women’s sports, LGBTQ+ student experiences, and Hispanic-serving institutions. The module includes a classroom teaching activity that uses campus historical markers to help students better understand the processes and contestations of historical commemoration.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.