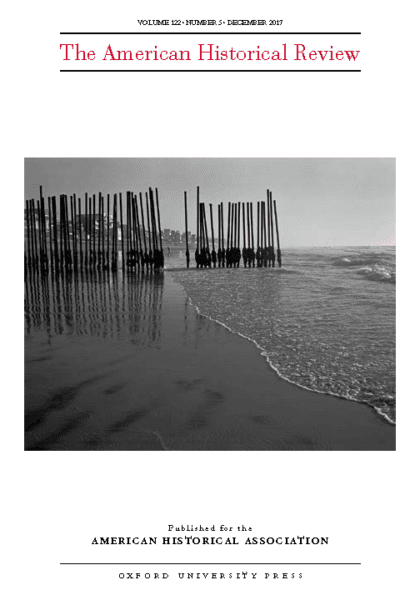

The AHR Conversation for 2017, “Walls, Borders, and Boundaries in World History,” has obvious relevance to present-day realities—from the much-threatened “Mexican” wall to the call from many in Europe to strengthen national border controls. On the cover of the December issue: the fence dividing the beach at International Friendship Park, on the US–Mexico border between San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Baja California, looking south from the San Diego side, 2012. Border crossings going in both directions between the cities of San Diego and Tijuana number 300,000 a day. Photograph © Andrew Lichtenstein. Courtesy of the photographer.

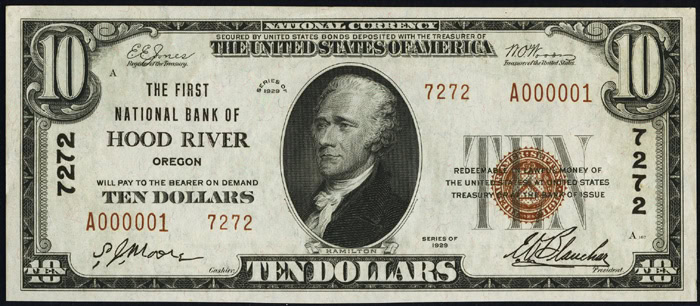

As Jonathan Levy (Univ. of Chicago) observes in his “Comment” in December’s AHR Forum (“Follow the Money: Banking and Finances in the Modern World”), the relationship between the ordering and wielding of power and the production and distribution of wealth is particularly unsettled in our current moment. Levy’s remarks appear in response to three articles in this issue that collectively address the role of bankers, financial instruments, and the flow of liquid capital in the modern world. It seems telling that we did not commission this forum, but rather that the three pieces came to us independently.

The first, “‘Who Hold the Balance of the World?’ Bankers at the Congress of Vienna and in International History,” by Glenda Sluga (Univ. of Sydney), revisits that old diplomatic chestnut by putting financiers, rather than statesmen, at the center of the remaking of post-Napoleonic Europe. Sluga argues that the bankers and their families played an outsize role at Vienna and other peace congresses of this era, and brought to bear emergent “conventions of sociability” on newly forged diplomatic and commercial networks. In doing so, these masters and mistresses of capital also came to advocate for early humanitarian causes dear to their hearts, particularly Jewish emancipation and Greek independence. Sluga’s essay contributes to the new history of capitalism, bringing social and cultural history to bear on an international past that too often has left finance out of the complexities of political settlement. In forging the 19th century’s European order, bankers, as much as politicians, it seems, cultivated the norms that came to characterize the nascent liberal tenets of a new international system, bending new fiscal and speculative norms to emergent humanitarian sensibilities.

The forum is bookended by another article that explores similar themes. Lila Corwin Berman (Temple Univ.), in her essay “How Americans Give: The Financialization of American Jewish Philanthropy,” illustrates how shifts in the culture of philanthropy worked in tandem with gradual transformations in the postwar US political economy. Financial deregulation and the privatization of many public goods nurtured philanthropy’s expansive fiscal power and allowed philanthropic capitalists to help craft state policy. Berman tells this tale largely through the lens of American Jewish history, but it would be a grave mistake to understand this as a purely Jewish practice. Philanthropic organizations of all kinds advocated for and benefited from tax policies that would allow them to redirect large pools of accumulated surplus capital into social welfare channels of their preference. While this helped disperse private wealth into a more public arena, it also redirected, and perhaps even eroded, state-centered commitments to building human capital. This, Berman (and Levy) argue, ultimately might have contributed to inequality more than to redistribution. One need look no further than today’s debates about charter schools, for example. And, as Levy notes in his comment, Berman’s line of analysis might raise some rather uncomfortable questions for the overriding goal of asset appreciation in the nonprofit sector in which many AHA members butter their bread: higher education.

Berman focuses attention on the contribution of one communal group to financialization; Sluga offers a financialized account of a single political moment more conventionally understood as an arena for diplomacy and high politics. The contribution to the forum by Vanessa Ogle (Univ. of California, Berkeley), “Archipelago Capitalism: Tax Havens, Offshore Money, and the State, 1950s–1970s,” reminds us that the power of financial instruments to remake the world easily leaps—indeed, obliterates—the boundaries of space, time, and nation. As she shows, a far-flung landscape (dare one say empire?) of tax havens, offshore financial markets, flags of convenience, and the economic equivalent of no-man’s land created an alternative universe to that of the powerful nation-states of the Bretton Woods condominium. This subterranean space of a free-flowing, unrestricted, and often invisible stream of capital proved a harbinger of the neoliberal world of frictionless transactions coupled with the growing social inequality and precarity that has come to define 21st-century modernity.

The obverse to the free flow of capital is the ceaseless effort to restrict the movement of human beings.

But the obverse to the free flow of capital remains the ceaseless effort to restrict the movement of human beings. If the former depends on lowering barriers to the instantaneous movement of financial assets around the globe, the latter rests, as always, on the erection of physical walls, borders, and boundaries—which happens to be the topic of our annual AHR Conversation (“Walls, Borders, and Boundaries in World History”). From the US–Mexico border (depicted on the cover) to Calais to Palestine, from gated communities to police checkpoints, this interchange among five historians and one literary scholar has obvious present-day resonance. Still, the participants in the ongoing online conversation, convened and led throughout 2017 by former editor Robert Schneider, sought to broaden the discussion across time and space, taking care to think about walls, borders, and boundaries historically and across a range of scales, temporalities, and territories. The participants in the discussion include Suzanne Akbari (Univ. of Toronto), Tamar Herzog (Harvard Univ.), Daniel Jütte (New York Univ.), Carl Nightingale (Univ. at Buffalo), Bill Rankin (Yale Univ.), and Keren Weitzberg (Univ. of Pennsylvania). Since their own areas of expertise range from medieval Christendom to modern practices of cartography, from the early modern Iberian empire to postcolonial East Africa, from urban segregation to household material culture, they come to the topic with a wide range of knowledge and perspectives.

A central theme that emerged as these scholars exchanged ideas over the course of several months was attention to the myriad ways humans have divided, policed, and otherwise drawn lines around territories, in what appears to be a near universal practice, despite (or because of) the ceaseless efforts of other people to breach such barriers. Equally illuminating are the different meanings people have ascribed to the walls, boundaries, and borders they have either created themselves or that have been imposed upon their societies by others. For some, it appears that good fences always make good neighbors; for others, borders were made for traversing, reshaping in the process the very social landscape the state meant to demarcate. As usual, the AHR Conversation will be continued at the annual meeting in January, as several participants will appear together on a panel (Saturday, January 6, 2018, from 3:30 to 5:00 p.m. in Washington Room 1 at the Marriott Wardman Park hotel). We invite you to join us.

Unrestricted speculative financial capital seeking the highest return coupled with growing restrictions on the ability of ordinary people to sell their labor to the highest bidder: such is the nature of today’s global capitalist free market. All that is solid melts into air indeed; this too has a history. Read about it in the December American Historical Review.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.