What can a sex scandal at an asylum tell us about Reconstruction-era politics in the Deep South? Why did a former slaveholder organize a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan only to quickly abandon it to join the Republican Party and work on behalf of racial reconciliation? This blog series centers on my experience learning how to use the records of a sexual misconduct investigation at the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum in 1871 to answer these questions. In three posts I will describe how examining these records forced me to reformulate my original research questions; how contextualizing this scandal complicated my view of the Civil War and Reconstruction; and how conducting research in archives and in the field shaped my understanding of how historians create knowledge.

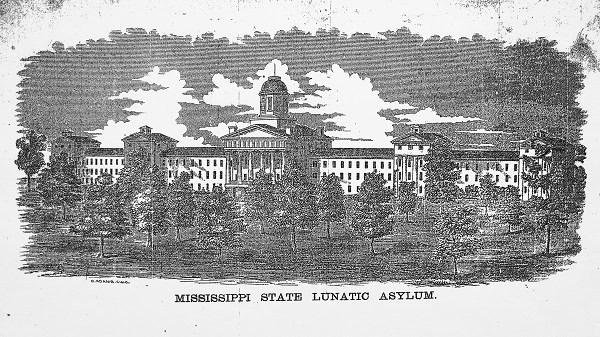

The Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum first opened in 1855 in Jackson and was demolished almost 100 years later in 1954. Today, the site is occupied by the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Two years ago, construction workers building a new road on the property discovered almost 1,000 unmarked graves containing remains of deceased residents of the asylum. Image from the 1877 annual report of the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The process of discovery has taught me that archival work, like writing and storytelling, is an artistic undertaking. I initially entered the archive seeking to understand how everyday people dealt with the trauma caused by the Civil War, narrowly defined as mental trauma and illness among veterans. Although I had hoped to find medical descriptions of conditions and treatments associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, the asylum’s records offered only the most rudimentary descriptions of its patients. Instead, I found testimonies from people involved in a sex scandal between the asylum’s superintendent, Dr. William M. Compton, and two nurses. After failing to force these records into the narrative I’d originally wanted to tell, I realized that if I could reformulate my research questions and “listen” to my sources, I could use the sex scandal to acquire a unique and fruitful understanding of postwar Mississippi. My project now examines how the ideological conflicts of the Civil War era played out in the political battles surrounding the asylum, and how Mississippians—not just traumatized former soldiers—struggled to make sense of the world that emerged after the conflict.

In this series, I will discuss how learning to creatively analyze my sources changed how I thought about my project. Instead of investigating the sex scandal as an event, I used it as a lens through which I could examine the political, social, and cultural upheaval of the postwar South. Contrary to the image of the asylum as an isolated community cut off from the outside world, my research showed that it was deeply connected to the rest of Reconstruction-era Mississippi. Jackson’s elite frequently visited the institution, participated in its “lunatic balls,” and supported it financially when the government could not. The asylum’s superintendent and assistant superintendent were also appointed by the governor, which made these postings highly coveted and contentious patronage resources. As a result, an event as salacious as the 1871 sex scandal was widely covered in the state’s newspapers, and the asylum’s superintendent became a symbol of Reconstruction’s (depending on one’s political affiliation) corruption or virtue. As such, the case offers a unique opportunity to study a post-emancipation world where lines between whiteness and blackness, sanity and insanity, bigotry and tolerance were constantly contested, blurred, and redefined. In time, I discovered that Reconstruction in Mississippi was actually composed of a thousand individual reconstructions occurring at the personal and intimate level.

My blog series will also highlight what I have learned about the limits of the archival record and historical memory. As I began to investigate Compton, one of the figures at the center of the scandal, I began to encounter new sources that complicated my view of the scalawag superintendent. Local historians pointed me to sources identifying Compton as one of the founders of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan who later became an advocate of African American civil rights. As fascinating as this transformation was, local memory downplayed his association with the Republican Party and adopted a more reconciliatory “Lost Cause” view of Compton—a feat made possible by his heroic death attempting to stop the spread of yellow fever in 1878. Decades later, his contemporaries remembered only his involvement with the Klan and his advocacy on behalf of white supremacy in the 1860s, overlooking his shifting position regarding race in the following decade. Understanding the divergence between local memory and the archival record reinforced for me the need to understand the many ways historical knowledge is created and preserved. This series will ultimately illustrate how the historical research process—in conjunction with graduate coursework—has taught me to embrace the messiness of the past, the folly of easy categorization, the utility of seemingly irrelevant sources, and the historian’s craft.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.