To this day, Shirley Kendall is surprised when she steps into a restaurant. “I look around and see, and I’m kinda amazed that I’m in a restaurant with other people, and I’m being allowed to be in there, because it still—apparently it still affects me. My feelings about being in a place like that.” I interviewed Shirley in July 2008. A Tlingit elder, Shirley was born in 1932 in Hoonah, Alaska. Under the law until 1945, and for years after in practice, Alaska Natives lived segregated from the white population in public spaces. Shirley’s experiences with that segregation never fully left her psyche—such is the legacy of segregation that produces racial hierarchies.

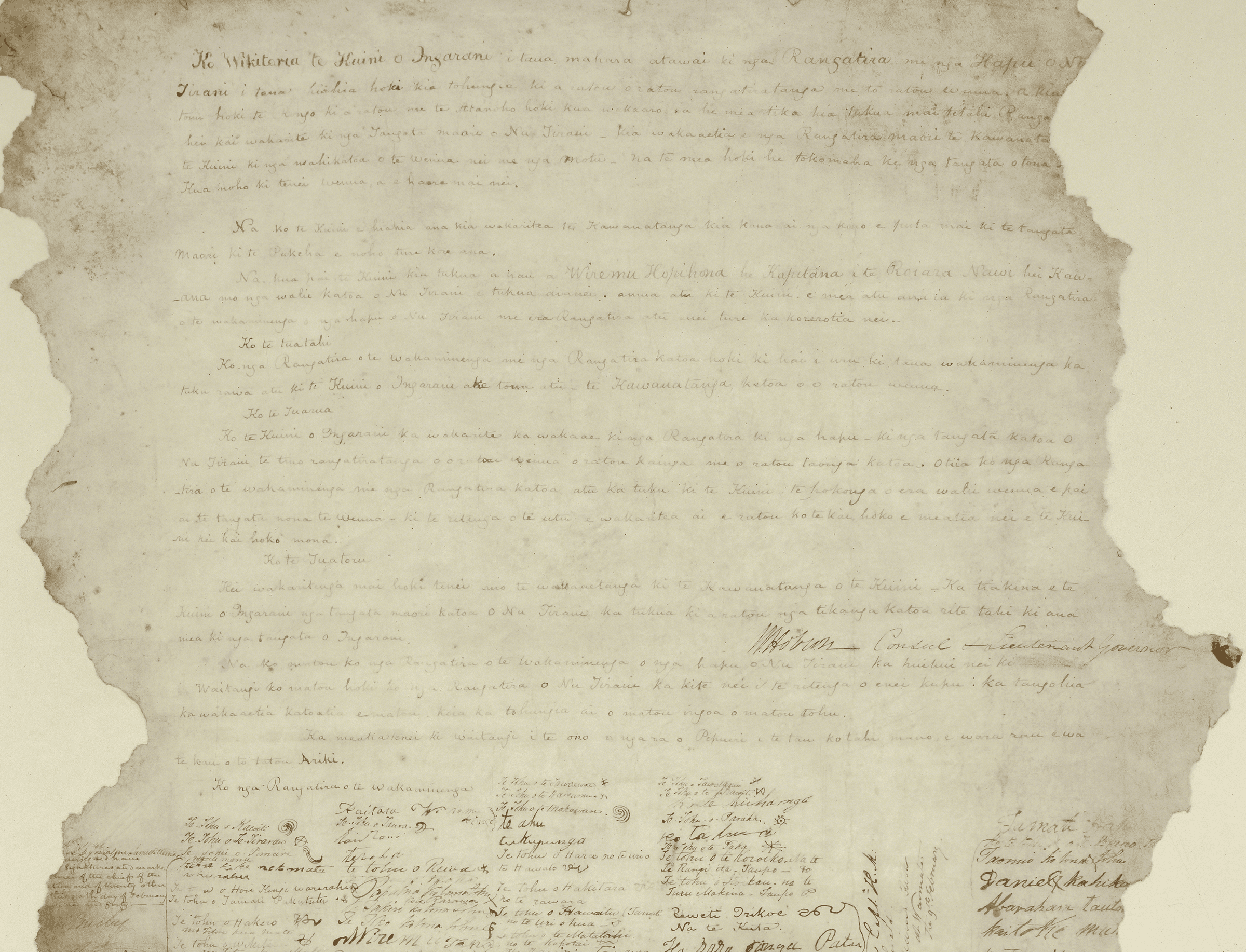

Alaska Native elders experienced segregation, discrimination, and boarding schools meant to “civilize” Indigenous peoples. Alaska State Library, Fhoki Kayamori. Photographs, ca. 1912–1941, ASL-P55-395

I have spent 14 years recording oral histories with Alaska Native elders, engaging as an active listener while believing and validating the stories they share. Many of these elders observed and experienced relocation and segregation in Alaska during World War II and the Cold War. They did so as young children while Western influences attempted to conform their minds in boarding schools.

While growing up in Anchorage, I rarely learned about Alaska Native history in school. The history I learned from my family included stories about the US government’s abuses. As a child, my mother was subjected to radioactive iodine testing of her thyroid during the Cold War. Other stories included family history with education, like the Bureau of Indian Affairs schools where my grandparents were punished by white teachers for speaking Iñupiatun. Although my public education in the 1990s leaned toward inclusive multiculturalism, local Alaska Native history remained largely absent from the curriculum, and multicultural education that included colonial myths of the first Thanksgiving downplayed structures of inequality in favor of an imagined postracial society. This multicultural education sought to sanitize Indigenous history and the histories of other marginalized peoples in favor of narratives that did not question structures of colonization and power—stories more palatable for a widespread audience.

Situating myself in this essay requires acknowledging the role between an interviewer and an interviewee, and my relationship to interviewees as a fellow Indigenous person (enrolled Iñupiaq). Such an acknowledgment fits within methods employed by critical Indigenous studies, where, according to scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou, Māori), research about Indigenous peoples by Western researchers is inherently linked to colonialism and imperialism. Therefore, oral history is my attempt to not only highlight the voices of Alaska Native elders but also enhance our understanding of Alaska history and its relation to a broader history of US imperialism. Most importantly, forming partnerships with community-based organizations became formative in my research experiences, where I received mentorship from the Alaska Native Policy Center and the First Alaskans Institute.

I became an oral historian my junior year of college while majoring in Native American studies at Stanford University. After reading historian Terrence Cole’s article “Jim Crow in Alaska,” I linked this secondary source to family stories about Alaska’s racial segregation of Native people prior to passage of the 1945 Alaska Equal Rights Act. I thought, “What do Native people themselves have to say about this time period?” I approached my adviser about pursuing such a project, but they declined to advise me and told me to go to ethnic studies. Here is where I learned about disciplinary exclusion and the need for supportive mentors. I emailed Matthew Snipp (Cherokee), who I had taken a course with my freshman year, and he encouraged me to pursue my project while securing research funds through the Community Service Research Internship at Stanford’s Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. I think of historical contingency often—in this instance, what if I had never taken a class with Dr. Snipp? He believed in my project before I began it, he supported me through advising, and he found research funds for me to travel back to Alaska.

Oral history highlights the voices of Alaska Native elders but also enhances our understanding of Alaska history and its relation to a broader history of US imperialism.

That summer, I met with 29 elders from across Alaska, most born before 1940, to talk about racial segregation. Two themes from these conversations resonated with me. Many elders, including Shirley, recalled sitting in separate sections of restaurants. Others described a federal project of total assimilation through cultural genocide. Like my grandparents, these elders recalled being physically and psychologically punished by white teachers for speaking Native languages. With the findings of mass graves at boarding schools in the United States and Canada, such neglect reveals a purposeful genocide of Native children. I wrote my findings into my senior honors thesis, “Rewriting the History of Racial Segregation in Alaska.” After college, I worked in Stanford admissions as a college counselor and an undergraduate Native recruiter, which sent me to various western states and Indian reservations. But eventually I decided to pursue a PhD and continue this history project.

Since I started conducting fieldwork with oral histories, I have viewed history as not only a field that needs decolonizing and greater inclusion of Indigenous perspectives but also a discipline that could link academia with the public. Oral history provides such a link—not only by integrating Indigenous perspectives missing from Western archives but also by hearing a voice reflect on a specific time period. The listener can connect with a speaker, hear about their life, and perhaps more readily empathize with them. Additionally, the testimonial form of oral history prioritizes the centering of human rights and a component of social justice. One can hardly listen to Unangax̂ relocation survivors without recognizing the gross neglect enacted by the US government, which followed familiar patterns of American Indian removals dating back to enslavement and relocation on the Eastern Seaboard in the 17th century. Here, oral history adds powerful voices otherwise downplayed, disregarded, and muted in more mainstream national US histories.

As I heard and recorded these stories, I saw it as essential to share them. Oral histories are meant to be listened to and learned from. Even when a transcript is available, it is best to listen to the audio, which offers human voice, character, intonation, and the interactions between the interviewer and interviewee. Today, when information is widely available online and recording technology on smartphones is easy to use, websites or YouTube channels allow people to listen to and learn from oral histories from their homes or in a classroom setting, a significant opportunity to disseminate information.

So I created a website of my own during a postdoctoral year at the University of California, Irvine. World War II Alaska allows history students and learners to explore testimonies from survivors of Unangax̂ relocation and internment, to listen to Native veterans who fought for Native rights on their homelands while encountering discrimination, and to try to understand the perspective of Native children during this era. These children saw massive military infrastructure fortifying their homeland, and they also had stories about the boarding schools. In one case featured on the site, Elizabeth Keating (Athabascan) explains that one of her older sisters died of medical neglect at a Native boarding school; her remains were never returned home. Listening to her story provides a necessary human component to narratives of siblings lost at such boarding schools. And she is not unique—other living elders remember siblings and cousins who died at those institutions. The images and news coverage of the mass graves do not always tell that personal story. This website allowed me to design a space for oral histories to be integrated with historical context, maps, and photographs. While at UC Irvine, Sharon Block mentored me and inspired me to bring my website to fruition. I must caution that such projects come with a cost. You must invest time and resources in learning to make a website, but there is also the expense of website hosting. While some platforms offer free hosting, they might require advertisements—a real trade-off that must be considered.

The images and news coverage of the mass graves do not always tell that personal story.

In addition to my digital history work, I still work with archives to preserve elder oral histories. Since 2016, when I first received funding from the American Philosophical Society (APS) Library, I have been preserving oral histories with their Center for Native American and Indigenous Research and their digital library. APS Library has generously supported dual preservation efforts that allow me also to maintain oral histories at tribal archives in Alaska. Preserving oral histories within tribal organizations supports efforts of Indigenous sovereignty and tribal oversight of community-based research. My oral histories with Unangax̂ elders are preserved at the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association Heritage Library in Anchorage; the Sealaska Heritage Institute has those with Tlingit elders from Juneau; the Iñupiat Heritage Center and Tuzzy Library have interviews with Iñupiat veterans; and all veteran oral histories are also at the Alaska Veterans Museum. Each organization has its own oral history projects that have aided my research, and for elders who consent to this method of preserving their interview, I am reciprocating information to maintain knowledge in the community.

In my teaching at the University of New Mexico, I emphasize the importance of bearing witness. My students and I discuss oral history content from other historians’ digital work, including the websites Japan Air Raids.org and Pacific Atrocities Education, podcasts, and YouTube channels. More recently, many of my students have preserved oral histories from a midterm assignment with the UNM Online Digital Repository. I maintain that oral history is a powerful way to reach out to students, academics, and the public, allowing us to recognize humanity at its core, from the voice of a survivor and the testimony they chose to share with the world. In listening to oral histories, we benefit as a humanitarian collective. Such stories are essential to understanding the human condition and the need to preserve human rights and humanity.

Holly Miowak Guise (Iñupiaq) is assistant professor of history at the University of New Mexico. She tweets @hollyguise.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.