We perhaps live in unparalleled times. Nostalgic shadows of a past historical-social world, one in which forms of genocide, colonialism, and racial domination were the order of the day, are now regularly invoked as solutions in a present that to some seems unhinged. The leading headline of the January 1, 2000, New York Times proclaimed the new century as “Past, Present and Future in One Stroke,” and that, for this century, the past was prologue.

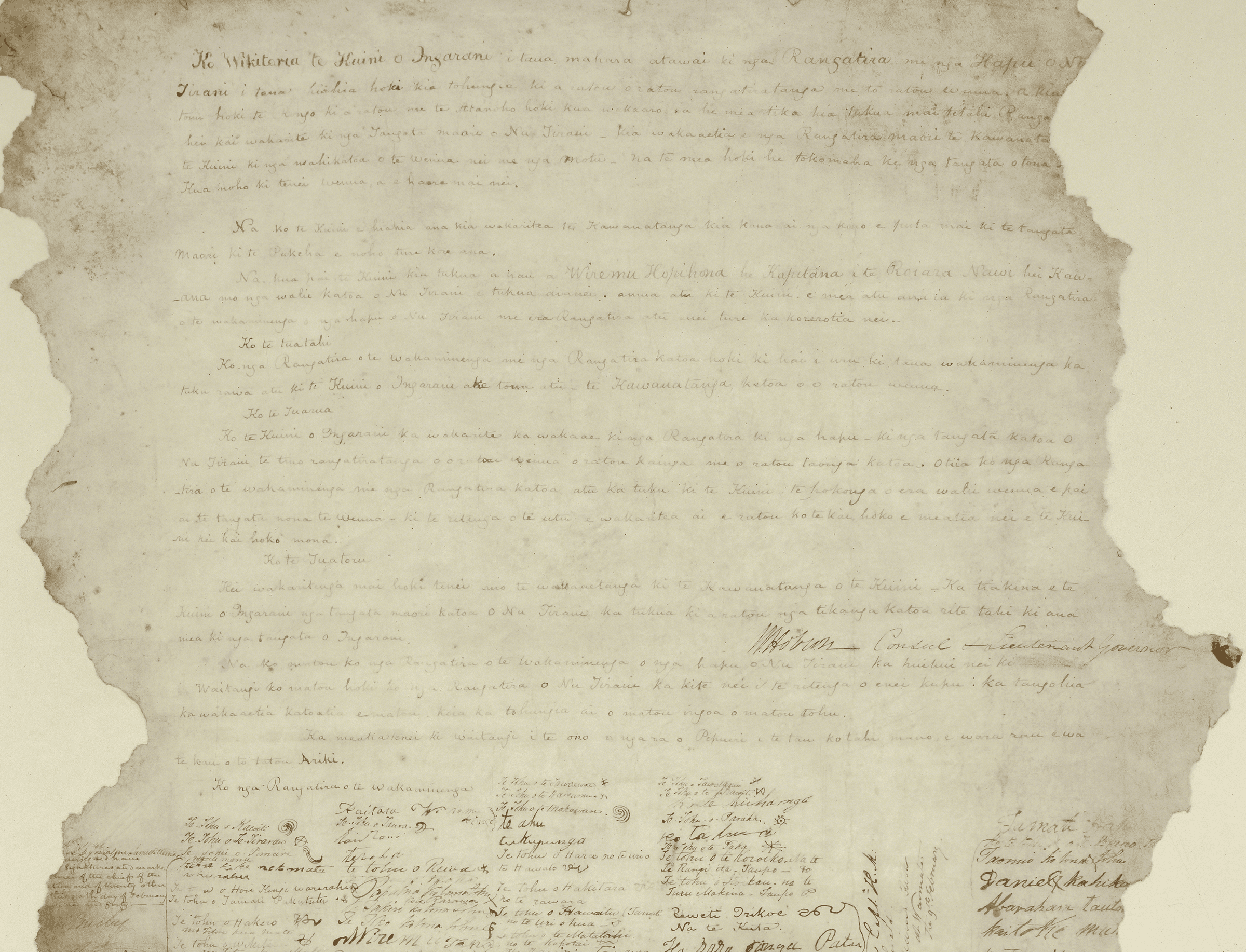

Under President Ruth Simmons, Brown University was the first American university to directly address its involvement with slavery. The Slavery Memorial, created by Martin Puryear, is one legacy of her tenure. Kenneth C. Zirkel/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA 4.0

Yet nearly a quarter century later, we might well ask, Which past? And, even more pointedly, whose past? The Haitian writer Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote in Silencing the Past (1995) that “history as a social process involves people,” thereby making “pastness a position.” We are in the midst of the nostalgic shadows that seem bent on returning to a version of the past in which white racial power held full sway and where elites governed without even murmurs of disagreement—a version where “alternative facts” have the power of mythic truth, having no relationship to occurrences but are structured through power. But there also have been points of light, attempts to grapple with a history in which the past is not prologue but rather shapes how history lives in the present—a living history.

Over the past 19 years, there have been numerous attempts by universities to grapple with the history that has shaped them. It is not an American phenomenon, since, as I write this, Cambridge University has just published a report on its historic links to transatlantic slavery and British colonialism. Museums around the world are grappling with their ethnographic and art collections as part of a colonial heritage that needs to be confronted and action taken. So one aspect of the moment we are in is that some educational institutions are trying to figure out what to do about the past. What is this “pastness” in the present?

What is this “pastness” in the present?

When then-president Ruth Simmons commissioned the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice’s Slavery and Justice Report in 2003—a report to which I and others contributed—she did so, in her words, because she was “seeking the truth, and doing something that was actually good for the University because the process would put to rest questions that some had posed about the corruption of the University, which had hidden the truth of its connection to slavery. So I thought that I was lifting up the University with the truth.” There is a vast historiographical literature about the complex relationship between history-as-event and the truth, the interpretation of the event. However, the matter becomes more complicated when the event is elided and deliberately hidden, or when its significance and meaning are ignored and relegated to a dim past separated from a present. In such contexts, history as a form of truth telling becomes critical. The issue here is not so much the facts—those can be unearthed through deep archival work. The issue is, what are the significances and meanings of these facts, and how do we confront them in the present?

In the process of the numerous meetings and debates, the Brown steering committee confronted the historical knowledge that some key members of the university’s corporation, including the Brown family, were involved in the slave trade. Others, like Stephen Hopkins—a signatory to the Declaration of Independence, a governor of Rhode Island, the first chancellor of the College of Rhode Island (which became Brown University), and the author of the important pamphlet The Rights of Colonies Examined—owned enslaved Africans. Two questions emerged: How would we name this past we now confronted, and what could we do about it?

In confronting these issues, the committee had to name this history. As the Caribbean novelist and thinker George Lamming noted in a 1956 speech at the Black Writers and Artists Conference in Paris, “A name is an infinite source of control.” So the committee often asked itself, what should we name American racial slavery? The committee decided that it needed to conceptualize American racial slavery as a historical wrong and a “crime against humanity.” This naming of the social system of American racial slavery opened the report to many criticisms, but at the same time, it allowed the report to raise the question of what forms of justice were required in the present to address the structuring legacies of racial slavery. Deciding on a concept of reparative justice, the report developed a series of recommendations, all of which were discussed broadly within the university and resulted in a plan of action. The recommendations ranged from public funds for the Providence public school system, more support for the Brown Africana studies department, a campus monument that addressed how founding members of the university were involved in the transatlantic slave trade, and the formation of a Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice.

In such contexts, history as a form of truth telling becomes critical.

The naming of the social system of racial slavery as a “crime against humanity” raised foundational moral and ethical questions about racial slavery and noted that, although support for the system was the dominant norm, there were also abolitionist voices. Racial slavery was not so normalized that there was no abolitionist opposition. Importantly, of course, there was the opposition of the enslaved themselves to the terror and violence that constituted their everyday experience, an experience that the formerly enslaved Olaudah Equiano called “constant war.” Yet if we do not move beyond this specific naming of the social system of racial slavery, and beyond a narrow approach that understands American racial slavery as a thing of the past, we might not fully discern how, as James Baldwin put it, “the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us. . . . It is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.” Following that line of thought, I would suggest that racial slavery as a social system was a historical catastrophic one. Historical catastrophe is a repeatable state of living. It is the persistent reproduction of terror and violence on a population over the longue durée. It both leaves structural residues and creates a dominant common sense about ways of life within a society. W. E. B. Du Bois once noted how American racial slavery was about the ways in which a human being was constantly under the “arbitrary will” of another. In human societal terms, we need to ask, When such a social system, despite formal changes, is constantly reproduced and is readapted with its residues, then what are its consequences on the structures of a society as well as on forms of life?

Today, we acknowledge that structural anti-Black racism is the living heritage of racial slavery, since that social system created not only structures of domination but a racial order embedded within these structures. Social structures are formal ways of life that are reproduced. However, such reproduction also works through forms of representation and discourse that create an imaginary. Dominant conceptions of the “history” of a specific historical period operate at the levels of ways of life and of the imaginary. This is why conservatism today is animated by historical nostalgic shadows.

Dominant conceptions of the “history” of a specific historical period operate at the levels of ways of life and of the imaginary.

All this takes us back to history and its presence in our contemporary world. For the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice appointed in 2003 by Dr. Simmons, we saw one of our tasks as opening up some of the silences in American history, doing what historian Jules Michelet once termed “speaking of what has not yet been spoken.” Yet the committee did not open all silences. After they landed, the settler colonists of Rhode Island and New England first embarked on the colonial project of dispossession of the Indigenous peoples of the region. Brown University is built on dispossessed Indigenous land. So in confronting that historical truth, another question concerning pastness as a position that faces the university is, how does it make repairs with respect to this past? That question now animates a university community that in the early 21st century confronted its history about racial slavery. Dispossession and racial slavery are two distinctive forms of domination, but they relate to each other in the structuring of America. The Brown report did not pay serious attention to Indigenous dispossession. Its absence points to how sometimes our historical gaze operates in silos.

We end where we began. We inhabit a paradoxical moment, one in which there are active currents that want to return American society to an imagined past that they believe can and should exist today. Then there is another current that seeks to confront the past of America as a slave and settler colonial society. In such a context, historical truth matters.

Anthony Bogues is the inaugural director of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice at Brown University, where he is the Asa Messer Professor of Humanities and Critical Theory and professor of Africana studies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.