What follows should be read in the context of two recent, related discussions among AHA members about the fate of historians’ libraries.

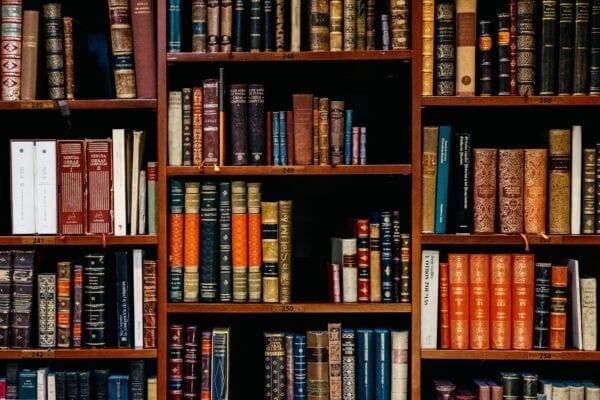

For those who have spent their lives with books, getting rid of them can be unexpectedly difficult.Iñaki del Olmo/Unsplash.

The first was the May 2022 retirement-themed issue of this publication; the second, a subsequent exchange in June that took place in the AHA Member Forum. Our aim here is to offer some additional observations, alternately sobering and hopeful, about the challenge facing many historians as they enter retirement and plan the fates of their working libraries: How to reduce the number or dispose of their books?

These observations grow out of our recent cooperation as historians of long acquaintance. In the summer of 2021, Jim began seeking to arrange the disposition of his history and other books to the Atlanta University Center (AUC) Robert W. Woodruff Library, a shared collection that serves the students and faculty members of four Atlanta historically Black colleges and universities—Clark Atlanta University, the Interdenominational Theological Center, Morehouse College, and Spelman College—the world’s largest consortium of such institutions. That search led him to the good offices of Jamil, who sits on the library’s board of trustees.

What set off the search for a fitting resting place for roughly 3,000 books was Jim’s wish to find an institution that might desire and have space for them. He could thus avoid having to consign a library of some coherence to a bookseller or to leave its disposition to his executors, both of which he preferred not to do. But what began as a simple desire turned quickly into a frustrating, sometimes dispiriting, endeavor, one whose realities that those writing about their preparations for retirement in Perspectives and the AHA Member Forum, as well as many others, will recognize.

Before he approached Jamil, Jim’s two attempts to find a new home for the books failed. Perhaps his high school would like to have his collection? “Thanks, but we’re no longer accepting books” was the disheartening response; “not enough shelf space.” How about a college or university library, especially that of a historically Black college or university, which might welcome a gift of books it didn’t yet possess? The leading such institution in his home city never responded to repeated phone and email inquiries.

He would avoid having to consign a library to a bookseller or to leave its disposition to his executors.

So what to do? Perhaps, Jim reasoned, it would help to go farther afield. Thus began conversations between the two of us, conversations that resulted in an introduction to Loretta Parham, director of the AUC Woodruff Library and a leading figure in the American library community. From further discussions with her and her senior staff members soon emerged a formal deed of gift. The legal document, a simple one, obligates Jim or his estate to release his books to the AUC Woodruff Library at a future, unstipulated date. Arriving at that agreement proved reasonably uncomplicated. The library, possibly unusual in this respect, required no collection inventory but, desiring some indication of what the collection contains, instead asked for photographs of a sample of the contents of Jim’s bookshelves. After determining that it could use a good proportion of his books, the library agreed to take all of them. To assure that unwanted books would end up, as the donor wished, with similar libraries, the AUC Woodruff consented to make a good-faith effort to place those books with other HBCUs.

No one should think that this happy result can easily be repeated. As the Perspectives issue and the AHA Member Forum discussion made clear, our experience was unusual. It came about by virtue of an old friendship—Jamil was able to open a door for Jim—plus the AUC Woodruff Library’s discovery that the future gift would add appreciably to its holdings. Nor do we believe that our approach to a general problem should be considered the sole or best option for all historians desirous of disposing of their libraries or that historians should bear central responsibility for resolving the many challenges that face all authors, libraries, and book owners today.

That said, other historians and the leaders of other libraries might find the arrangement that resulted from our cooperation of interest. After all, such an approach holds out promise of reciprocally serving the desires of individual historians to find appropriate resting places for their collections of books and the needs of many small baccalaureate colleges (by no means exclusively HBCUs), historical societies, and K–12 schools whose libraries may welcome gifts of books. In addition, this kind of arrangement strikes us as a more mutually beneficial means of disposing of books than others that are frequently resorted to: tag sales, the random distribution of books to students and colleagues, or—frequently as acts of desperation—recourse to local booksellers who offer no more than a pittance for what has taken a career to amass. Yes, the obstacles to such arrangements are many. But that doesn’t mean that those obstacles can’t be overcome.

Prospective gifts of books should ideally have easy going with their prospective recipient institutions. But that’s not the case today. Libraries are in transition because of budgetary and space limitations, the digital revolution, and resulting changes in patrons’ expectations and experiences. While book gifts may reduce an institution’s budgetary outlays for book purchases, such gifts require shelves to contain them, and many libraries have become short of shelving as well as of the funds to add more. Furthermore, book cataloging, which requires experienced library staff members, is increasingly costly. Libraries, which must be mindful of the interests of their users—students, faculty members, and members of the general public—are likely to discriminate in what they choose to receive and hold. When offered books, many prefer to see full inventories of collections before they accept them, a burden on prospective donors they may not be willing to undertake. In short, giving books away can prove hard going.

Libraries ought to be more forthright in seeking collections of books for which they have need and space.

So, you’ll ask, is the search for suitable homes for historians’ personal libraries worth the effort? We think it is—as long as you’re willing to run the possible obstacle course to the finish line. Many professors have approached their institutional librarian only to be told that “we’re now accepting only rare books; in fact, we’re not accepting the papers of even the most long-serving and distinguished of our retired faculty members.” Or they’ve been turned away by librarians who tell them with a rueful look that they’re only buying e-books. Thus, consequently, we welcome what’s often the easiest solution to a complicated challenge—that smiling book dealer willing to haul away the books that your family members don’t want.

All of this is to say that whether Jim’s arrangement can be repeated elsewhere with the same ease is unclear. Yet we think it’s worth identifying and directly approaching institutions you consider fitting for your books; if you can do so through an intermediary, all the better. The hoped-for mutual benefits of a gift of books go without saying. On the donor’s side lies the benefit of federal and possibly state charitable gift deductions, while the institution, of course, receives the books.

But it also seems to us that libraries ought to be more forthright in seeking, from alumni, faculty members, and others, the collections of books in the specific subjects, not just history, for which they have need and shelf space. Disciplinary societies like the AHA and the Organization of American Historians—indeed, many of the constituent societies of the American Council of Learned Societies and consortia of baccalaureate colleges like the Council of Independent Colleges—could serve as auspices for the exchange of information about what specific subjects their libraries have identified as needed to strengthen themselves, if possible through donations. Furthermore, such arrangements ought to lead libraries to intensify their efforts to attract alumni or others’ donations of books in subjects of which they’re in particular need.

We offer these thoughts and suggestions in the spirit of furthering discussion of how to alleviate a general problem in ways mutually beneficial to historians and the institutions that support their work and that of their students. What’s now important is that discussions continue and that additional workable ways to address the problem be found.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.