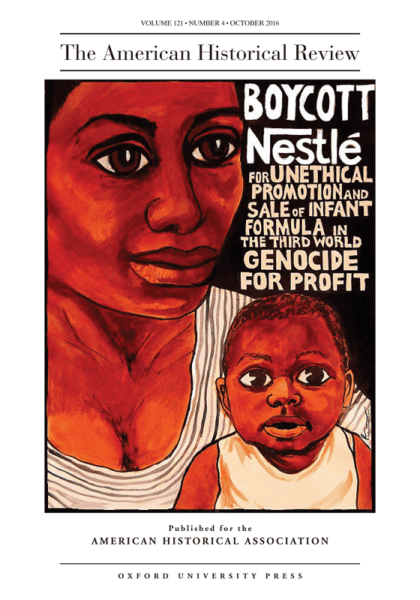

In 1977, humanitarian activists launched a global boycott against the Nestlé corporation, a well-known manufacturer of infant formula. As part of a campaign to end bottle-feeding in Third World societies, the boycott called for regulating controversial strategies being used by Western multinational companies to market breast milk substitutes to women in underdeveloped nations. In the increasingly global and deregulated economy, activists claimed, multinationals like Nestlé exploited vulnerable consumers and profited from Third World female poverty. Both citizens and aid experts took part in the boycott, which led to the creation of the first international set of standards regarding global corporate responsibility. In “Milking the Third World? Humanitarianism, Capitalism, and the Moral Economy of the Nestlé Boycott,” Tehila Sasson argues that while the dangers of bottle-feeding were known before the 1970s, it was only in this period that a movement of “global citizens” mobilized and transformed this knowledge into a new moral and political economy of “ethical capitalism.” In the process, Sasson shows, boycotters positioned residents of the underdeveloped world as global consumers, not just producers. Boycott Nestlé, 1978. Artist: Rachael Romero, San Francisco Poster Brigade.

The October issue of the American Historical Review includes five full-length articles that range from a study of abolitionist ideology in early 19th-century Sierra Leone to late 20th-century global humanitarian efforts in the Third World. The issue also contains eight featured reviews and our regular book review section.

In the opening article, “The Colonial Rebirth of British Anti-Slavery: The Liberated African Villages of Sierra Leone, 1815–1824,” Padraic X. Scanlan reconstructs and interprets the early history of the Liberated African Villages of Sierra Leone, a group of settlements built for former captives rescued from the Middle Passage by British ships after the 1807 abolition of the slave trade. Designed to be most effective in wartime, British abolition turned slave ships under any flag into prizes eligible for capture by the British navy. At the same moment, in Sierra Leone, a colony with a long-standing association with British antislavery, the end of the Napoleonic Wars caused an economic shock. The colonial governor, Charles MacCarthy, established the Liberated African Villages both to organize the labor of former captives and to manage and distribute colonial resources. His “village system,” organized from the colonial capital, Freetown, was managed in the hinterland villages by missionaries recruited by the Church Missionary Society. What began as a plan to shore up the postwar colonial economy became, in practice, a potent engine for social engineering, cultural transformation, and labor control spearheaded by missionaries and former abolitionists. As Scanlan shows, British antislavery was remade as a new and expansive colonialism in the Liberated African Villages.

Scanlan’s article is followed by Daegan Miller‘s “Reading Tree in Nature’s Nation: Toward a Field Guide to Sylvan Literacy in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” which takes up American environmental and cultural history. In 19th-century United States, trees were used for nearly everything: fuel, food, shelter—even for roads. But individual types of trees also remained freighted with a host of specific cultural connotations: white pine trees signified, among other things, New England, and palms, the South; oaks were often figured as royal, Christian, and male, while apple trees represented a bedeviling mix of intoxicating female temptation and the promise of virtue’s everlasting life. Trees were symbols, and as symbols they constituted a sylvan literacy on wide display throughout 19th-century images and texts. Miller’s essay traces a history of sylvan literacy, from its rise in the nature-based cultural nationalism of 1830s United States to its eclipse in the early 20th century, caused by the language of professional forestry. Miller’s essay also advances a theory of how sylvan literacy worked: more like poetry than a dictionary, open to multiple, competing interpretations, and put to contesting uses. Ultimately, his essay contributes to the cultural and environmental history of the 19th-century United States by arguing that learning to “speak tree” can help translate a complicated, still unresolved US culture struggling to root itself securely in a shifting world made by both humans and nature.

The issue’s next essay moves from matters of sylvan to fiscal legibility. In “A Fiscal Revolution: Statecraft in France’s Early Third Republic,” Stephen W. Sawyer argues that a hitherto undocumented fiscal shift occurred in France during the 1860s and 1870s, several decades prior to the transformative impact of the nation’s income tax. While this first French fiscal revolution actually increased economic inequalities, it also prepared the foundation for a new state-society relation that proved essential for the creation of the income tax. In this earlier period, Sawyer demonstrates, Third Republic statesmen used new indirect tax revenues for state spending and debt financing far beyond the military—especially for new services like mass public education and transportation, among other areas. By uncovering this earlier fiscal revolution, Sawyer’s article points toward a revision of some of our central historiographical assumptions on the timing of state building and fiscal power. Sawyer explains that the relative invisibility of the regressive indirect taxation in this era was largely intentional, designed to disguise its inegalitarian nature and consequences. At the same time, an intellectual history of late 19th-century French taxation reveals that emergent professional economic science in France and beyond was deeply committed to the income tax and therefore insistent upon the prior system’s frailty and insufficiency.

Laurie Marhoefer‘s article, “Lesbianism, Transvestitism, and the Nazi State: A Microhistory of a Gestapo Investigation, 1939–1943,” brings readers of the journal fully into the 20th century. In recent decades, the Nazi state’s murderous campaign against gay men has drawn attention. But historians remain at odds over the question of whether lesbians were persecuted as well. Marhoefer argues that historians ought not to limit themselves to the notion of “persecution” and rather ought to consider risk—that is, how lesbians, “transvestites,” and gender nonconformists faced pronounced, particular risks in a society that stigmatized same-sex sexuality, transgender, and gender nonconformity. Her argument advances some fundamental reconsiderations of the category “lesbian” itself, as well as the functioning of the Gestapo. Marhoefer’s close reading of a single Gestapo investigation into the life of a gender nonconformist reveals the important role of witnesses (as opposed to denouncers) in producing risk as well as the multiple meanings of the category “lesbian” in the Third Reich. Ultimately, this microhistorical article puts forward new ways to think about the history of lesbianism, gender nonconformity, and trans history, as well as new ideas about the inner workings of Gestapo and Nazi repression.

The October issue concludes with Tehila Sasson‘s article “Milking the Third World? Humanitarianism, Capitalism, and the Moral Economy of the Nestlé Boycott.” Sasson traces the history of one of the most well-known and successful boycotts of the 1970s, the campaign against Nestlé’s infant formula. As part of the campaign to end bottle-feeding in Third World societies, this boycott called for the global regulation of controversial marketing strategies implemented by Western formula companies. The story adds a crucial, yet understudied, aspect of rights discourse in the 1970s, when humanitarian activists strove to reform the global market and create ethical forms of capitalism. The history of the Nestlé boycott may seem like a marginal tale within this history, but in Sasson’s hands it illuminates the intersecting roles of multinational companies, ethics, and the market in the period, and adds to the global history of human rights and humanitarianism. The history of the boycott campaign uncovers how, in the 1970s, not only diplomats and nongovernmental organizations, but also ordinary people, business experts, and even multinationals themselves joined the project of feeding the world’s hungry. By politicizing breast-feeding, the boycott played an important role in transforming the ways in which aid programs conceived the Third World and its peoples—that is, from producers to consumers in the global marketplace. While international attempts to limit the power of multinational corporations ultimately failed, the Nestlé boycott represented a potential solution that emphasized the moral responsibilities of corporations. It thus offered a limited form of utopianism that emerged after the end of empire and sought to reform global inequalities through, rather than against, the market.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.