How did the United States become what The Economist magazine recently referred to as the “jailhouse nation”? This was the question that three leading historians of incarceration addressed in the National History Center’s latest congressional briefing, held in a House hearing room this past Friday, October 9.

The statistics on the subject are staggering: the United States currently incarcerates 2.3 million people, a larger proportion of our population than any other nation on earth. Although Americans comprise only 5% of the world’s population, our country accounts for 25% of the world’s prison inmates. Over the past 40 years, the number of imprisoned Americans has increased 500%.

Understanding how this social disaster has come about demands a historical perspective. The briefing brought together three leading experts on the subject—Alex Lichtenstein, associate professor of history at Indiana University; Khalil Gibran Muhammad, director of the Schomburg Center at the New York Public Library; and Heather Ann Thompson, professor of history at the University of Michigan. All have written widely on the history of incarceration in America, and Muhammad and Thompson have served on a National Research Council blue ribbon panel on the causes and consequences of incarceration in the United States.

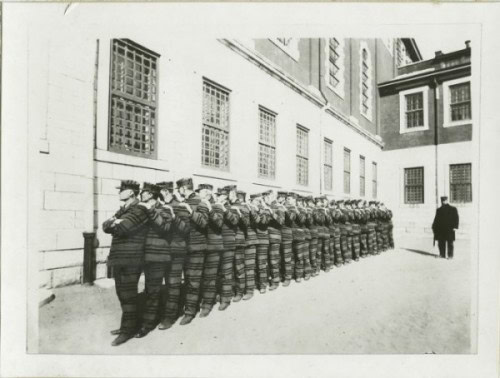

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Line of prisoners at Sing Sing Prison.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 13, 2015.

Alex Lichtenstein opened the session with a survey of US penal practices from the early 19th through the early 20th century. He argued that every new mode of incarceration—the first penitentiary, the Auburn factory prison system, the South’s use of convict leasing, followed by its turn to chain gangs—was presented at the time it was introduced as a reform designed to treat prisoners more humanely. Yet each would come to be seen as cruel and ineffective. The lesson Lichtenstein drew from this history was the need for skepticism about claims of reform: deeper questions need to be asked about why we incarcerate, whom, and for how long.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad followed up on Lichtenstein’s concluding comments by turning attention to the issue of race. Blackness has been associated with criminality in America since the Puritans, and racial pathology has been used to explain the disproportionate number of blacks incarcerated in the country’s prisons. By contrast, Progressive-era reformers advocated compassionate social solutions for the white violence that plagued northern inner cities at the turn of the century. Although the Prohibition era and its mandatory sentencing requirements threatened the mass incarceration of whites in the 1920s, the repeal of Prohibition and the rise of the New Deal led to more progressive, less punitive policies. The principal takeaway from Muhammad’s presentation was that American justice has never been color-blind.

Finally, Heather Ann Thompson carried the story of US incarceration practices from the 1960s to the present. The era of mass incarceration that began with the “War on Crime” in the 1960s was not a response to high crime rates, Thompson pointed out. Crime rates began to spike after draconian sentencing policies were instituted. What provoked those policies were economic agendas and racial politics, which criminalized African-American spaces, suppressed political dissent, and disenfranchised those who have been incarcerated. Like Muhammad, Thompson stressed the danger that mass incarceration poses for democracy itself.

The issue of mass incarceration has attracted increased public attention over the past year or so, with an abundance of stories on the subject appearing in the national media and calls for reform coming from spokesmen across the political spectrum. Contributing to this conversation was the June 2015 special issue of the Journal of American History on the history of the carceral state. (Muhammad and Thompson served as guest co-editors of the issue, and Lichtenstein wrote an essay for it.) The tide, it seems, is turning against the harsh sentencing policies that have been in place since the 1960s. In the past week alone, the Justice Department has announced the early release of 6,000 prison inmates under new US Sentencing Commission guidelines, and a bipartisan group of senators have proposed new legislation that would reduce mandatory prison sentences for individuals convicted of nonviolent crimes. These are encouraging developments. But as the presentations of the panelists and the subsequent question-and-answer session made clear, mass incarceration is a problem that extends far beyond the walls of prisons. Its causes are rooted in racism, unemployment, poverty, inadequate educational opportunities, economic exploitation, and other social ills. The panelists agreed that the United States will continue to be a “jailhouse nation” so long as those ills remain unaddressed.

Director, National History Center

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.