Spring semester, another 20 to 30 students in the room, here we go again—HIS142: Traditional China.

The faces are new each year, but the composition of the crowd is familiar. At the University of Rochester, where I teach, students in history courses come from a broad range of majors, including biology, chemistry, economics, electrical engineering, political science, art history, English, and, of course, history. They come to this class to gain a deeper knowledge of a current global superpower, to fulfill cluster requirements in the social sciences, or to gain insights on specific topics, like the Mongols, the Silk Road, and the eastern “isms” (Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism).

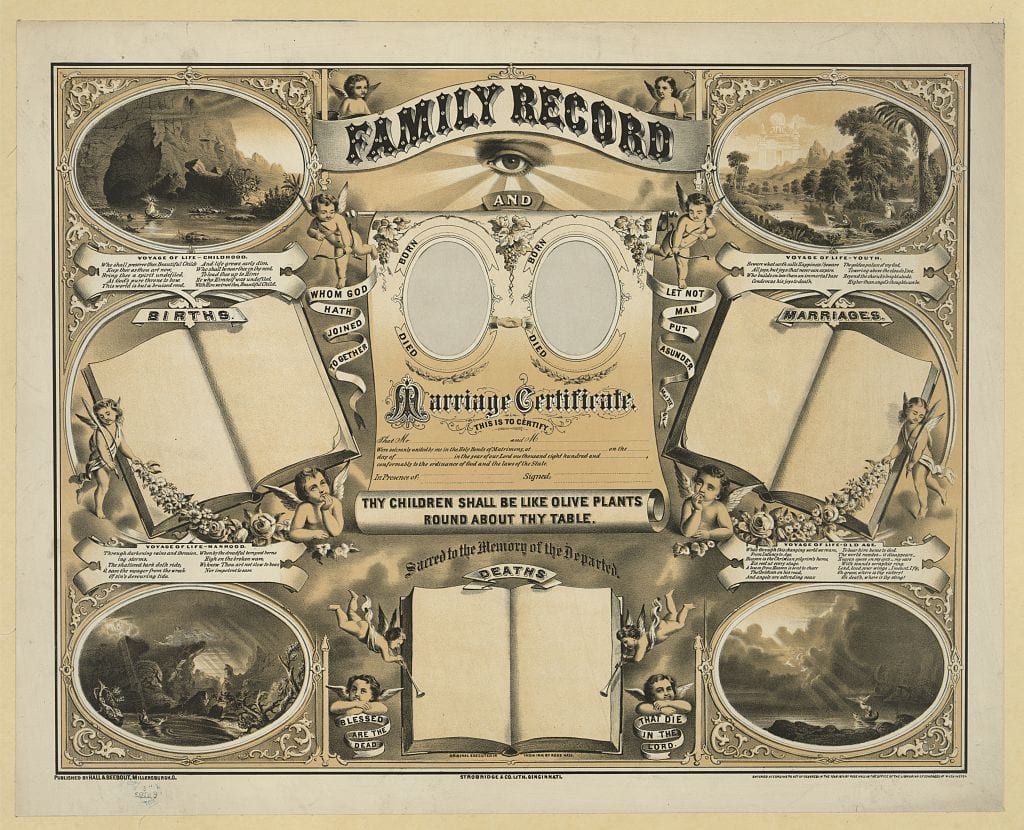

University of Rochester student T. E. Scheuerman titled her “face” class project “Our Sister Painter.” T. E. Scheuerman/Courtesy Elya Jun Zhang. Used with permission of the artist.

By and large, though, they don’t intend to major in history. Yet if I make this class memorable, a good number of them might decide to take more history courses. Traditional China is only one among the large pool of regional or thematic courses that my home department provides: the Atlantic, the Caribbean, knights, Stalinism, disease, world wars, Native Americans, the African diaspora, and more. Undergraduates at Rochester usually make sure that every course they take counts toward at least one degree. That’s why each additional history course they take could be the tipping point that prompts them to pursue a history minor or even to double-major in history.

My approach to creating memorable classes is to let students take ownership of their learning through individualized challenges, many with a digital focus. In courses of all sizes and levels, I include a “mechanism” to nudge students to jump an extra creative hoop between their reading and writing assignments. Discovering digital tools particularly appeals to them. For instance, students in my upper-level spatial history courses learn to use basic ArcGIS software to translate their research findings into professional-looking maps, which then serve as visual scaffolding for their final papers. And students in my modern history surveys formally debate current dilemmas in class and share their arguments and evidence online.

But for my premodern history surveys, like Traditional China, I use Photoshop to have students insert their own faces, literally, into the distant past of a distant land. This is an effective way to teach historical empathy, one of the most important competencies our discipline can impart. Our creative project, “Once upon a Time in China,” has students use both texts and digitally remixed images to conjure up their own Chinese “person,” making history come to life. Most of the grade for the project depends on a solid biographical essay detailing this fictional person’s occupation, personality, exploits, dilemmas, and the fabric of their larger historical world. Before any words appear on paper, however, students must create the face of their “person” by inserting a picture of their own face into a Chinese-style traditional painting.

This aspect of the assignment requires a solid plan to enable even the least tech-savvy students to create with confidence. They need to find quality background images and learn the basic skills of graphic design. I was fortunate to have the help of Joe Easterly, my university’s digital scholarship librarian. Two vast online databases—the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access Artworks collection and Artstor—became our main sources. There are around 1,700 images of genuine Chinese-style paintings in the Met’s publicly accessible collection, and students can register for a free account with Artstor Digital Library, a nonprofit organization, to use their images for educational purposes. (University libraries often have Artstor accounts of their own.)

Joe and I selected Photoshop for its straightforward logic (treating each image as an editable layer) and availability (already installed on every public computer on campus). In an hour-long test tutorial session, two other librarians and I, despite lacking previous Photoshop experience, all picked up enough fundamentals to create personalized images. The students proved to be fast learners: we had reserved two class sessions for student tutorials, but more than half of the class completed multiple “snapshots of time” to choose from before the tutorials ended.

Each additional history course my students take could be the tipping point that prompts them to pursue a history minor or even to double-major in history.

After creating their remixed images, students wrote vigorous biographical essays. Their “personae” came from every century of 3,000 years of premodern Chinese history, with fictional lives carefully correlating with actual historical events. Students’ interests in other fields also came in handy. An art history student dreamed up a convincing “hidden” female painter in 18th-century China, based on the existence of several famous Jesuit paintings from the imperial Qing court collection. (The artist’s identity is ambiguous.) A Navy ROTC student charted a Ming Chinese sailor’s accidental shipwreck in Kenya, making good use of her notes from a marine navigation class.

Interestingly, students also seemed to inject real-life predicaments into the fictional figures, whose faces, of course, were theirs. Originally, I thought that ambitious young adults, given an opportunity to freely insert themselves into the past of a distant land, would naturally want to be powerful leaders. But essay after essay proved me wrong: students were interested in the humbler, more complicated side of history. There was a farm boy who traveled with Daoist monks for the 30 best years of his life, only to realize that the quest for immortality is an illusion; a servant friend of Marco Polo who was the true author of the explorer’s famous travelogue but died young and anonymous; a Manchu princess who was forced to separate from both her parents and her Han Chinese husband during the bloody Ming-Qing dynastic transition; a merchant who amassed wealth from war but saw his idealistic son run to battle and die; a young man with homosexual inclinations who failed both his Confucian-official father and the rebel leader to whom he had sworn loyalty.

These historical “personae” were not heroes; they were displaced, isolated, and misunderstood in their lifetimes. Perhaps they reflect the thoughts of people who came of age during a financial crisis and now face a world dominated by political and environmental crises. These students seem to understand that contemporary conditions, like the partisan divide, racial conflicts, and social tensions created by mass migration, are not unique to our times. Their fictional figures also struggled with intractable dilemmas: whether to run north or south during the 3rd-century Period of Disunity, whether to be radical or conservative in the 11th-century Green Sprout Reform, or whether to seek pleasure or redemption under the 17th-century “barbarian” minority rule.

This wary streak of realism, reinforced by spotting one’s own face in the historical mirror, is probably exactly what is needed for imparting historical empathy, which lies in our ability to understand why someone in the past felt and acted in a certain way, given the context of the world in which they lived. Teachers have always tried to help students personally relate to historical information, transforming dry-as-dust facts into genuine knowledge, but this can be a struggle in teaching ancient and medieval subjects, so far distant from students’ experiences. With this project, however, students excitedly jumped into the past after one Photoshop tutorial. Using their imagination and their own faces to complement the facts and narratives they knew, the students became more rigorous historians themselves. The past was still distant, but they were eager to develop their skills in empathy to bridge the gap between then and now.

An art history student dreamed up a convincing “hidden” female painter in 18th-century China, based on the existence of several famous Jesuit paintings.

The students’ creations are displayed on our course website under six categories: art, business, government, war, traveler, and drifter. I hope the division can give readers a nuanced sense of the tones that each fictional-historical figure adheres to. For interested readers, the website also contains an assignment instruction sheet and a step-by-step Photoshop tutorial that we composed to guide students through the “Once upon a Time in China” project. There are still anachronistic errors in the biographical essays—we wish we could have had another three weeks in the semester to fine-tune the details. But these students’ genuine urge to create and take their history learning personally is a precious thing that I, as a teacher, cherish.

But did I accomplish my original purpose of making a basic survey course closer to the students’ hearts, so that they would linger longer in history courses in general? Where is the smoking gun to prove it? I inquired at the Office of the Registrar, where our students’ four years of study were boiled down to a simple list of abridged course titles and numbers. Using three years of Traditional China rosters—2015, 2016, and 2018—the Registrar staff looked into 58 students’ enrollment records to see if they had taken more history courses afterward, and found that 59 percent (34 out of 58) of my students had. When the freshmen and sophomores were examined as a separate group, the result was similar: 62 percent (16 out of 26) of the underclassmen dabbled in history courses again after Traditional China.

Maybe the project was the tipping point, maybe not. And maybe these 58 students already intended to take more history courses. But it’s possible that coordinating thoughtful, individualized assignments that students can make relevant to themselves is a good way to hold their interest in history beyond a single course.

Now I really look forward to next spring’s new faces in Traditional China, and the fresh “faces” they put on history.

Elya Jun Zhang is assistant professor of history at the University of Rochester. Visit her website at https://zhang.digitalscholar.rochester.edu/home/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.