Editor’s Note: This is the second of three articles reporting findings from the spring 2010 survey of research and teaching practices. The first article, “A Profile of the History Profession, 2010,” appeared in the October 2010 issue. Discussion of these findings will be part of the session “What’s Next? Patterns and Practices in History in Print and Online” scheduled for Saturday afternoon at the January 2011 annual meeting.

The recent AHA survey of research and teaching shows that while very few historians can be considered power users of digital software and tools, most are deeply immersed in new media and thinking critically about its effect on the way they do history.

The survey of history faculty at four-year colleges and universities asked an array of questions about the types of software and digital tools historians in academia were using, their publishing practices in print and online, and their general attitudes toward the technologies and opportunities of new media. But to provide a basic frame of reference, AHA staff classified the 4,182 respondents from U.S. institutions into four groups, based on their self-described patterns of adoption and use of new media.1

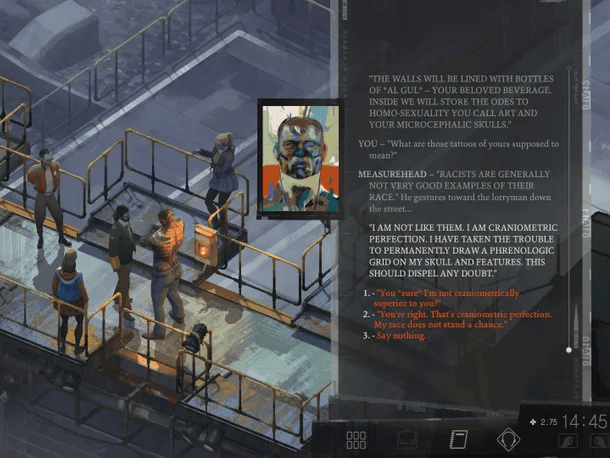

Figure 1

The number of “power users” in the discipline—those who said they are quick to adopt and make significant use of multiple digital technologies in their research and publishing—was quite small, comprising just 4.3 percent of the respondents (Figure 1). But more than two-thirds of the faculty in history departments could easily be classified as “active” users of new media. These historians said they regularly use online sources for their work, employ a variety of different technologies for their research and writing, and tend to adopt new technologies with some regularity and teach themselves how to use them.

These two types of users were distinguished from a much smaller group, classified here as “passive users” (24.4 percent of respondents), who limit themselves primarily to using their computers as word processors and for occasional online searches. They also rely heavily on others to teach them how to use new programs and technologies.

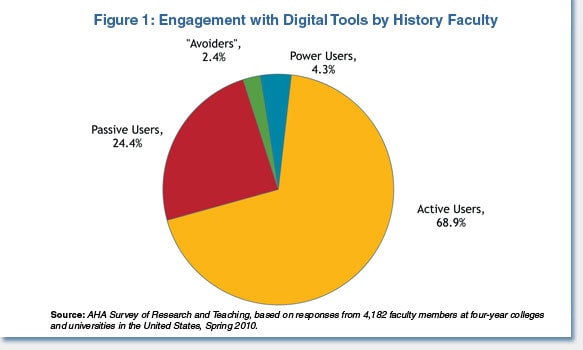

Figure 2

Lastly the survey turned up a small slice of historians (2.4 percent) classified here as “avoiders.” These respondents describe themselves as very reluctant users of new technologies. While almost all of them used word processors and conducted some online searches, they tended to adopt new software only when pushed by someone else (administrators, family, colleagues, and others).

As you might expect, there were significant generational differences between these groups, though not quite as large as the prevailing anecdotal wisdom suggests. Faculty members over the age of 65 were twice as likely to be grouped among the technologically ambivalent or hostile as faculty under 45 (Figure 2). Just over 40 percent of respondents over the age of 65 fit into the passive user/avoider group, as compared to 19 percent of the respondents under 45. Of course, that still means that 60 percent of the historians over the age of 65 said they were actively involved with a variety of new media for their research.

There was very little variation along the other demographic markers used in the survey—geographic field of specialization, type of employing department, and gender. European historians and men were slightly more likely to be in the passive user/avoider category, but this is attributable to the differences between the age cohorts (since older historians are more likely to be men and specialize in European history).2

The Tools of Research and Writing

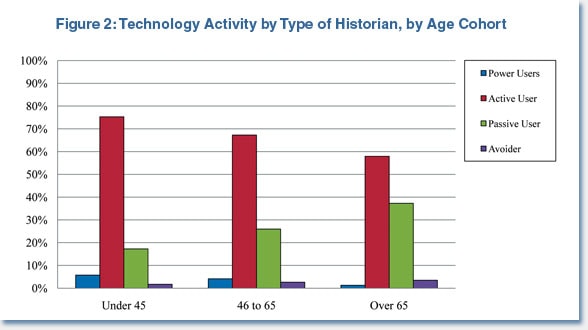

In practice, most historians use word processors and conduct online searches as a regular part of their research, but they also reported wide use of other programs and tools, including digital scanners and cameras, and a variety of other programs for organizing their materials and crunching data (Figure 3).

Figure 3

There were wide differences in use between the power users and the rest of the discipline in the range of technologies used to produce their research and scholarship. But these tend to be differences in quantity as much as actual use. The power users tend to use a larger number of programs on average than their peers (with an average of 8.0 programs and tools selected, as compared to 5.9 among active users, and 3.9 among the passive users). But overall, 74 percent of the historians in this survey said they use at least one program or technology beyond simple word processing and online search and databases.

Once again, there were interesting generational differences on the mix of technologies in use. For instance, older historians were more likely to use sophisticated programs for crunching numbers (such as SPSS) that came up during the heyday of quantitative history, while younger historians used simpler spreadsheet programs (such as Excel) for that kind of work.

While they are using an array of tools, the respondents expressed a range of reasons for taking a slow or cautious approach to adopting new technologies. Excluding the power users, half of the respondents in every category said they simply lacked the time to learn new programs, while a quarter of them expressed frustration at how quickly software and related skills grow obsolete.

Almost half of the passive users and avoiders (49 percent) also emphasized that they found very few programs and tools valuable to their research. As one respondent in this category noted, “new technology, while apparently ‘sexy,’ often doesn’t deliver on promises and takes valuable time away from actual research.” In comparison, less than a quarter of the historians more actively engaged with new media mentioned the utility of digital tools as an issue.

Well over half of the power users saw no cause for reluctance to adopt new software or digital tools. A quarter did express some concern about the time it takes to learn new programs, but aside from that, their largest complaint was about the lack of institutional support for new skills.

Changing Attitudes and Opportunities for Publishing

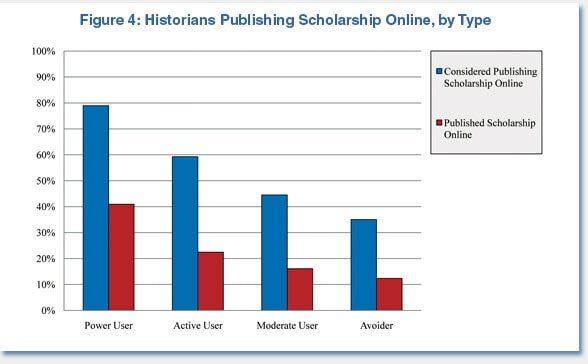

Aside from the general problems and practices of historians, the survey focused specifically on changes in the publishing of history scholarship. Slightly over half of the faculty in the survey said they have considered publishing their scholarship as an online article or e-book, and almost one in five said they actually had published some portion of their scholarship online (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Use of new media did not entirely determine the attitudes and publishing practices of history faculty. At the two extremes of our classification system, 21 percent of the power users said they had not considered publishing their scholarship online, while a significant portion (34 percent) of the technological “avoiders” expressed some interest in online publishing. And 12 percent of the technological avoiders said they actually had some online publications.

Interestingly, there was very little difference among the different age cohorts on these two questions. More than half of the faculty in every cohort except those over the age of 75 had considered publishing online, and around 20 percent of each age cohort said they had actually published some of their work online.

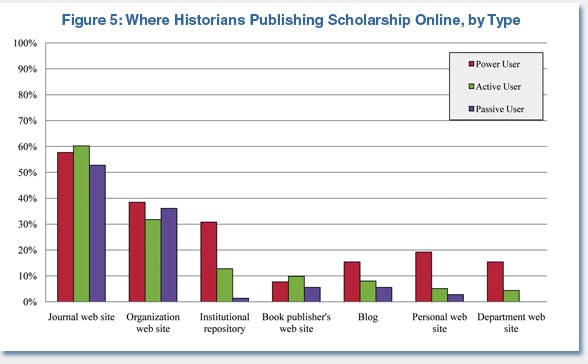

There is some ambiguity about what they actually published online, however. The question asked them not to include digital versions of their print books or journal articles in their count, but most said their work was published on a journal’s site (Figure 5). The respondents also noted a range of other outlets for their scholarship that highlight some of the opportunities and hazards for history scholars, ranging from organization web sites (such as the Center for History and New Media) to personal blogs and web sites. And among many of the respondents, the definition of scholarship seemed fairly flexible. In the open responses about where their scholarship was published, respondents included a wide variety of other publication venues, including web sites aimed primarily at teachers, digital documentaries, and even Wikipedia.

Figure 5

The scale of interest and array of forms and outlets for publication point to a growing issue in the discipline—that the forms and opportunities for publication seem to be outpacing the tools for assessing them in the monograph-focused reward systems of higher education. This has been a recurring question in recent years, about what becomes of history scholarship as the system for producing traditional monographic scholarship comes under growing strain.3

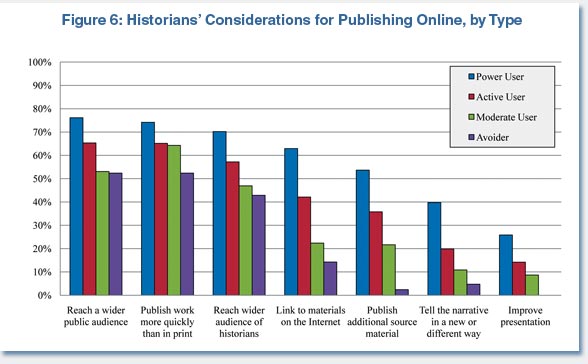

The reasons historians gave for considering (or actually) publishing online help to demonstrate some widely varied (and sometimes contradictory) perceptions of the benefits of online publication. Among those who have considered publishing online, the principal benefits were seen as reaching wider audiences and speed to publication, with a slightly higher proportion indicating a preference for reaching a general audience than an audience of their peers (Figure 6).4

Figure 6

Use of new media to do something new or different with the scholarship was a very minor consideration, however. Less than 40 percent of the respondents who had considered publishing online listed linking to other materials, publishing additional sources, or telling their stories in a new way as part of their thinking.

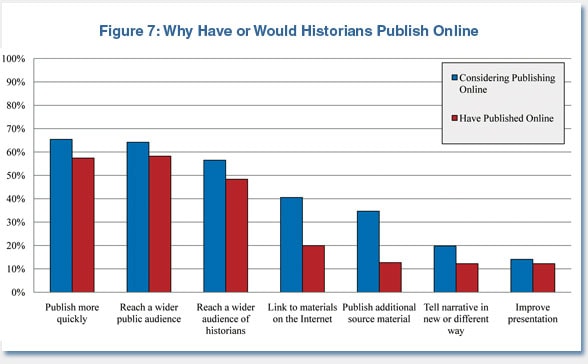

The preference for reach and speed is even more pronounced among historians who actually had published their scholarship online (Figure 7). On questions of speed and audience there was only a small difference between the opinions of those thinking about publishing online as a prospect, and those who had actually done it. In contrast, there was a significant gap on the value of linking to materials and publishing additional sources. Partially this was just a sharpening of attitudes based on actual experience creating digital publications. Those who had published online tended to focus on just one or two things of particular value—and typically reaching a wider audience and speed to publication rose to the fore.

Figure 7

Notably, there was a significant difference between the power users and the rest of the published historians on these issues, as they were two to three times more likely to emphasize doing something new or different with the medium as the value of publishing online.

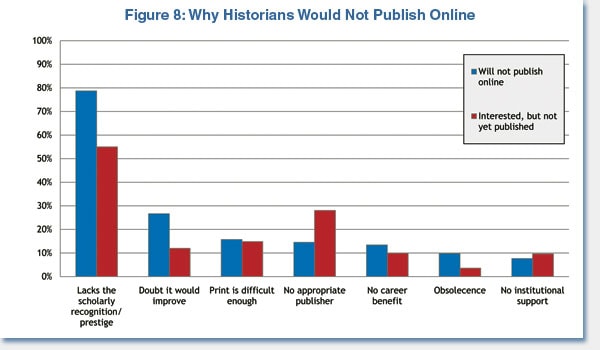

At the other end of the scale, faculty who have not yet published any form of electronic scholarship offered a number of fairly specific reasons for not publishing online (Figure 8). Far and away the greatest reason for shying away from online publication is the perception that it lacks the scholarly recognition and prestige of print publication. And a quarter of the respondents who had decided against online publication expressed doubts that it would improve the resulting scholarship.5

Note that the historians who were positively considering online publication were less concerned about the problems of scholarly prestige, and more concerned about finding a publisher and the lack of support for such work at their home institution.

Figure 8

Despite the concern about scholarly recognition in the academic reward system, there was little difference between tenured and tenure-track faculty on these questions. Among historians on the tenure track, almost 55 percent of faculty members pre- and post-tenure said they had considered publishing their scholarship online. The only substantive difference was that tenured faculty were slightly more likely to have actually published their scholarship online.

The AHA’s experience with the Gutenberg-e program demonstrated some of the conflicting problems in venturing into new media scholarship. While many in our survey expressed concern about whether their online work would get adequate credit, in Gutenberg-e we found that all the scholars who came up for tenure received it based on their digital books. It often took some work with department chairs and deans to reassure them that these should be accepted on a par with print monographs, but ultimately all of the authors who made it onto the tenure track have been successful so far.

While getting the works past tenure committees was feasible, getting them reviewed in journals proved incredibly difficult. In many cases, editors told us this was due not to doubts about the works themselves, but the lack of procedures at the journals for taking an e-mail link or letter and passing it along to a reviewer. Other editors expressed confusion about the kind of reviewer they should ask, since it was not clear whether they should get someone to review the scholarly content in the book, the electronic form and supplements, or both.6

These seem like difficult challenges for adoption of online media in our discipline, and will probably only be solved when more digital books come online and the intermediaries in the legitimation and reward process develop the necessary tool kits of procedures and assessment benchmarks to make this work efficiently.

The results of this survey of historians offer some useful clues about where the discipline is headed on these publishing issues and some of the potential hurdles along the way. The broad engagement with digital technologies by history faculty suggest the need for a better scale for thinking about what the digital humanities tools and online publishing represent for a field like history. From the scholars at the bleeding edge to those slowly and carefully adopting new tools into their research and writing, the history discipline may have its eyes on the past, but it is clearly doing so embracing the technologies of the future.

Versions of this report were presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of University Presses and the Sustaining Digital History conference in the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Thanks to Roger Schonfeld, Doris Malkmus, Margaret Stieg Dalton, and the members of the AHA’s Research and Teaching divisions for their advice and assistance in the development of the survey instrument.

Notes

- This classification was based on responses to four questions in the survey, “How often do you use electronic applications and resources when conducting your research?”; “Thinking back over the past five years, how did you tend to adopt new software and technologies to conduct research?”; “Which methods do you use to learn new software and technology?”; and “Which of the following software applications and resources have you used in your research?” For instance, someone classified here as a “power user” said they always or often adopt and use new technologies for their work, teach themselves how to use new programs and hardware, and use five or more of the tools listed. [↩]

- For more on the demographics of respondents to the survey, see Robert B. Townsend, “A Profile of the History Profession, 2010,” Perspectives on History (October 2010): 36–39. [↩]

- See for instance, Leigh Estabrook, “The Book as the Gold Standard for Tenure and Promotion in the Humanistic Disciplines,” Committee on Institutional Cooperation, 2003. [↩]

- This differs slightly from the evidence in the recent Ithaka S+R survey of academics, which found that faculty members in all disciplines preferred to publish for their peers. Roger C. Schonfeld and Ross Housewright, Faculty Survey 2009: Key Strategic Insights for Libraries, Publishers, and Societies, 25–26. [↩]

- This aligns with an important recent qualitative study on the attitudes of historians, which found that scholars in the discipline “face a higher burden of proof to demonstrate directly the value multimedia publications add to the development of the closely-reasoned argument that defines traditional historical scholarship.” Diane Harley, Sophia Krzys Acord, Sarah Earl-Novell, Shannon Lawrence, C. Judson King, Assessing the Future Landscape of Scholarly Communication: An Exploration of Faculty Values and Needs in Seven Disciplines, Center for Studies in Higher Education, UC Berkeley (January 2010). [↩]

- See AHA, “Closeout Report to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the Gutenberg-e Fellowship and Publication Program, December 1998 to March 31, 2008.” [↩]