World languages are sometimes just a footnote in the teaching of history. When I started teaching French, I thought the same about history. I occasionally peppered my lessons with the historical ties between France and the Francophone world. Most textbooks identify these different regions but gloss over the main reason why French is spoken there: colonialism. I spent some time trying to figure out how to engage students with this historical aspect of language learning. I found it best to bring colonial history directly into the classroom.

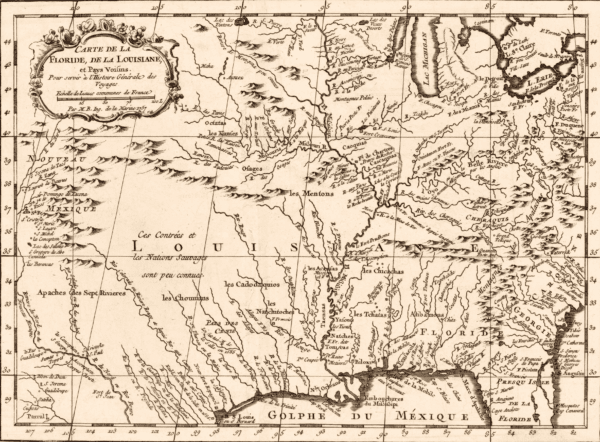

With this map of North America, Dennis Bogusz’s French students learn about language and place-names, including ones familiar to them today. Carte de la Florida, de la Louisiane, et pays voisins: Pour servir à l’Histoire générale des voyages, 1790. Library of Congress / public domain.

This frank approach helps students learn language through history, and sometimes vice versa. Having experimented with teaching about colonialism at different levels of French in middle and high school classes over the last few years, I’ve seen this approach unlock a deeper understanding for students. I share some examples below of what I find specifically helps students connect the historiography of language with colonial history.

For starters, even nonlinguists can appreciate how easily things can get lost in translation. When my students study French in North America, one of the first people they learn about is Jacques Cartier. When Cartier inquired about the inhabited parts along the river he was exploring, the Iroquois told him the area was called “kanata,” by which they meant a small village or settlement. Students quickly grasp the irony of the term that Cartier and other Europeans used for what would later name the world’s second-largest country by area.

On a map of colonial Florida and Louisiana, students find not only French but many Native American names they had not seen before on maps written in English. When students sound out in French the phonetic transcription of Native American terms, such as Cheraquis for Cherokee and Checagou for Chicago, they understand that English spelling was just one representation of Native American spoken languages. I also draw their attention to the phrase on the map “Ces Contrées et les Nations Sauvages sont peu connues” (These lands and savage nations are hardly known). I first check that students understand the literal French. Then I ask why they think the cartographer chose these words. Distinguishing between lands that were known and unknown highlights the relative ignorance of a Eurocentric view of America.

As a simple thought experiment, I prompt students to discuss how they know France exists if they have never been there. Drawing on their knowledge from history classes, we also take on directly what they think Europeans meant by “savage.” We discuss how English speakers use that term today, whether to describe people, places, or animals. (I point out that referring to historical people as savage is definitely passé in both France and the United States today.) Discussing who got to name things from different cultures in the past helps students appreciate that language itself has history. That these “savage nations” were labeled as such pushes students to develop their own questions. One question posed by a student that sticks with me was whether European settlers thought they could tame or civilize other peoples, which invited a larger discussion about the goals of the colonial project in North America and how it was perceived in Europe. We return to this concept when we visit the civilizing mission of later waves of French colonization elsewhere.

Drawing on their knowledge from history classes, we take on directly what students think Europeans meant by “savage.”

When my students later study migration in North America, they learn the difference between two words associated with Louisiana but often conflated. One is Cajun, derived from the word Acadian, which refers to the French speakers the British displaced from Canada and who settled in Louisiana. The other is Creole, originally from the Spanish criolla, which refers to the mix of language and culture from Caribbean immigrants who also settled in Louisiana. The term would eventually distinguish Louisianans by race as well. My students learn the distinctions between these terms as they also evolved in relation to music, food, and culture more broadly.

This year, I invited a Louisianan to visit the class. He explained the race-based connotations of the terms, with Cajun being generally more associated with whites and Creole with people of color. This alerts students as to how language evolves yet can retain a race-based legacy. My students had read about legal changes in Louisiana, which once accommodated French as an official language until it was ultimately suppressed not long after the state’s admission to the union. Our guest speaker shared how previous generations in his own family were forbidden from speaking French in school. There is a resurgence in demands, however, to bring the language back through educational programs and the media. Students then learn that today the word Creole in English is more geographically limited to Louisiana and the Caribbean, but that European French speakers use créole to describe a host of language communities stretching to the Indian and Pacific Oceans that blend French and other native languages.

Once students are primed to connect language with history in class, they do so outside too. I once chaperoned a class trip to Boston that was designed with a joint English-history curriculum. Not willing to let the opportunity to sneak in some French go by, before the trip I showed videos of French-speaking tourists on the Freedom Trail, which we would soon visit. During our time in Boston, students naturally stuck to speaking English most of the time. Then during a visit at the Museum of African American History, one student asked me why the Frederick Douglass calling cards on exhibit were labeled by their French name: carte de visite. Indeed, the term in English is historical; in modern French, it means business card. The student was impressed that Douglass was associated with an artifact that used French to distinguish its bearer as someone of high social status.

After our trip, I invited students to write a summary of their visit for a French-speaking audience. We then used these summaries to prepare for an in-class debate on terminology. Referring to our lesson before the trip and our Freedom Trail visit, students explained when to use the words freedom and liberty in English, since liberté can be translated into either word. Playing the role of naive French speaker, I further pushed them to explain why the French-gifted Statue de la Liberté is not called the Statue of Freedom. Students had to think critically about how they use both liberty and freedom, providing an insight they admit would not necessarily have been gained from a colonial history class taught only in English.

Students had to think critically about how they use both liberty and freedom.

A related use of literature is also central to understanding language and colonial history, revealing connections students may not make in history classes alone. I offer my students the chance to celebrate the literary giants who hail from Francophone America. For instance, they read excerpts from Guadeloupean novelist Maryse Condé, who wrote about Tituba and the Salem witch trials in Moi, Tituba sorcière . . . Noire de Salem. References to Tituba in English, whether in historical context or in related works of fiction like Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, usually refer to her as a secondary character. Condé shifts the narrative in her novel to Tituba’s perspective and makes her the protagonist. Likewise, my students’ perspective about the Salem witch trials shifted after reading from her perspective in French. (This novel is also available in English translation as I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem.) Though one of my objectives in the exercise is to get students to apply various past tenses in French, the more abiding lesson I have found is that students express how race, religion, and language collided in colonial Massachusetts, which may be less attainable in English-only literature.

I often ask students to write reflections on their learning throughout the year. Inevitably, they express, even if in imperfect French, the new and complex connections between language and history they are learning to see. Importantly, they deepen their knowledge of history through learning another language. Implicating students in the historiography of language can help them better understand social and cultural history more broadly. Teaching about France’s role in the North American history of colonialism also helps them understand the impact other European languages, especially English and Spanish, likewise had on the world students have inherited. Plus, as I point out to them, this approach offers a timelier approach to studying France itself, which like the United States is reckoning with its colonial past in the teaching of history today.

As these examples show, understanding how language and history are in conversation with each other yields deep student engagement. The pedagogical task is also mutual: Whereby language teachers can certainly bring history into the language classroom, history teachers can bring the study of languages into the history classroom. This interdisciplinary approach can afford students opportunities to make new connections and to appreciate the power of language in making history.

Dennis Bogusz has taught middle and high school French in New York City and Connecticut.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.