National History Day award winner Kelli Susemihl displays her research. Marc Monaghan

I begin with a confession: I had never previously attended an AHA annual meeting poster session.

But as incoming president-elect at the Denver convention, I decided to sample a number of different events, including the poster sessions on Saturday, January 7. The posters were conveniently set up in a main corridor of the cavernous Colorado Convention Center, which meant that many people wandered by during the day, some of them stopping to talk to the presenters. In addition, a steady trickle of others like myself worked their way down the whole row of posters—12 for each of two sessions, 11 for a third, on both sides of six corkboards.

Robert Caldwell analyzes inaccurate maps of Native American language evolution. Marc Monaghan

I was impressed by the wide range of topics, the creativity with which some of our colleagues presented their work in that format, and the different stages of research and thinking represented by the posters. But first I need to acknowledge that the finest visual “poster” of all (actually, an exhibit on a tri-fold stand) came from a student: the National History Day (NHD) Senior Individual Exhibit winner, titled “The Transcontinental Railroad: Exploring the West, Encountering Pitfalls, and Exchanging Culture,” presented by Kelli Susemihl of LeMars Community High School, Iowa. Her proud mother occasionally filled in when she took a break from talking to admiring historians. Congratulations to Kelli for a great job. The AHA will continue extending such invitations to NHD winners in the future.

Presenters included graduate students researching dissertations, professors near the beginning or the end of research for books, an archivist, an editor, people demonstrating digital projects, high school teachers engaged in rethinking the US history survey, and public historians. Some distributed handouts that amplified their posters. All were there to explain their work to the passing parade of historians. The rest of this essay constitutes an impressionistic survey of a few of the posters and their themes. Apologies in advance to the many I have necessarily omitted.

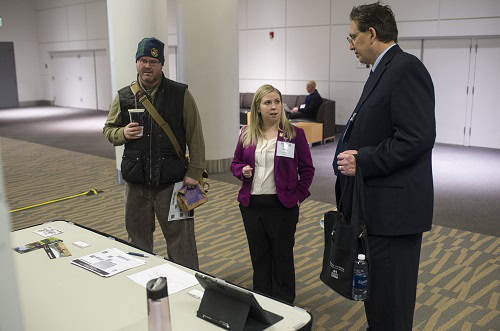

Two historians listen to Hilary Miller expound on a 19th-century highway. Marc Monaghan

Some of the most visually effective posters focused on cartography. Especially striking and complex was Robert Caldwell’s “Mapping Indian Country,” which showed the evolution of representations of Native American languages and cultures from Albert Gallatin’s 1836 map to William Sturdevant’s in 1967. Caldwell (Univ. of Texas at Arlington) demonstrated that the static and ahistorical maps he displayed were flawed and inadequate. Other posters employing cartography to good effect were “Mapping the ‘National Road’: Tracing the Creation and Expansion of American Culture and Identity along a 19th-Century Highway,” by Hilary Miller (Penn State Univ., Harrisburg), and “After the Fall: Opportunities and Land-Use Changes in the Longleaf Pine Ecosystem, 1880–2000,” by Stacy Roberts (Univ. of California, Davis). An unusual poster created a map where there had been none: Barbara Ellen Logan (Univ. of Wyoming) offered “Movement and Containment: Using Social Network Analysis to Map How an Anchoress’s Ideas Traveled When She Could Not.”

Barbara Ellen Logan’s poster mapped the spread of one woman’s ideas. Marc Monaghan

Other posters usefully employed reproductions of historical artwork. Patricia Baker (Univ. of Kent) contributed “Salubrious Spaces: Gardens and Health in Roman Italy, 150 BCE–CE 100,” including ancient wall paintings of gardens and medicinal herbs. With a poster focused on representations of Dutch Brazil, 1630–54, Georgia State’s Suzanne Litrel compared negative Portuguese accounts of the Dutch colony with (for example) a painting by Frans Post and prints of flora and fauna by other Dutch artists. University of North Carolina, Greensboro, archivist Keith Gorman’s poster looked at efforts to mobilize students at North Carolina women’s colleges during World War I.

Some posters originated with public history projects. Erik Johnson of the National Park Service traced “The Fall and Rise of Denali: The History behind the Mountain’s Name.” Grand Valley State’s Scott St. Louis used photographs of Victorian furniture made in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to explore the construction of civic identity there. Then there was my own particular favorite: “‘Our Eyes Are on the Stars’: A Rose Parade Float as Public History,” presented by Katherine Sharp Landdeck of Texas Woman’s University, which illustrated the process of creating a prize-winning float in 2014 honoring the WASPs (Women Airforce Service Pilots) of World War II, who ferried planes across the United States so that male pilots could be deployed elsewhere.

Viewing the eclectic posters and engaging with some of the enthusiastic presenters turned out to be one of the highlights of my annual meeting experience. I strongly recommend that attendees in the future copy my example. I know that I will be back.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.