The Public Record Office (PRO), London is the official repository of the archives of British central government departments and courts of law. Its holdings range chronologically from The Domesday Book (1086) to records relating to a Committee of Inquiry into the Conduct of Local Authority Business in 1986. Its ninety miles of shelving hold many millions of individual documents: parchment rolls, wooden tallies, deeds, wills, despatches, reports, log books, posters, maps, photographs, technical drawings—even a couple of jigsaw puzzles. This article aims to explain the basic principles under lying the arrangement of the records and how to set about using the PRO, and to describe some of the major sources likely to be of interest to American historians.

The Public Record Office is not a library: this is a truism which cannot be repeated too often. Its holdings are arranged according to the court or department which created them and, as far as possible, according to the administrative structures within which they were created. The records of each body are designated by a letter code which is sometimes self-explanatory (e.g., ADM for Admiralty, FO for Foreign Office) and sometimes not (e.g., BW for British Council). Each series “class” of records produced by a body is given a number (e.g., ADM1: Admiralty and Secretariat Papers; ADM 2: Admiralty and Secretariat Out-letters; ADM 3: Admiralty Minutes…). Each volume, file, or box within the series is given a further ”piece” number, so that each unit of production has a unique PRO document reference.

Because the records are arranged administratively and because they are so extensive, there is no single nominal or thematic index to their con tents. Researchers seeking information about a particular topic or event need to begin by asking, “Which government department is likely to have been involved in or concerned about this?” Such an administrative approach can widen a search in surprising directions. A paper I gave some years ago on the mapping of the Alaska boundary involved research in the records of the departments as diverse as the Foreign Office; the British Embassies in Washington and in St. Petersburg (because the United States and Russia were involved); the Colonial Office (because Canada was involved); the Treasury (because the British government was spending money; the Admiralty and the War Office (because officers of both ser vices were employed on the surveys); the Cabinet Office (which discussed the views of the Canadian government); as well as the papers of Sir Stratford Canning who was British ambassador to St. Petersburg at the time of the original boundary negotiations with Russia in 1824. A search for a file known to have been raised by His Majesty’s Stationery Office (about the printing of maps at the time of the Alaska Boundary Survey Convention of 1906) showed that the file in question had not been preserved, British Parliamentary Papers—not public records, but available to readers in the PRO—were another fruitful source.

So how does one set about identifying such disparate sources? The basic finding aid to the contents of the PRO is the Public Record Office Current Guide. It has been published on microfiche, and anyone planning to undertake research in the PRO would be well advised to consult it before coming to the Office. It is arranged in three parts:

- Part 1 contains an administrative history of each government department, court of law, or other agency which created the records. It outlines its organization and functions, and identifies the classes of records it created.

- Part 2 contains a brief description of the nature and contents of each class of records.

- Part 3 is an index to parts 1 and 2.

It should be borne in mind that the Current Guide constitutes only the first level of information about the holdings of the PRO: i.e., at class level. It does not contain, details at “piece level”—i.e., of each file or volume—let alone at the level of individual despatch or report. None of the above-mentioned wealth of material on the Alaska boundary would have been identified by looking up “Alaska” in part three of the Current Guide—indeed, “Alaska” is not even entered there. This is not to discount the usefulness of the Current Guide, but to emphasize that it is not intended to do more than indicate classes of records which might be worth searching. The alphabetical index (part three) does contain nearly two pages of entries under “United States,” ranging from “United States Air Force” to “United Kingdom Food Missions during and after the Second World War,” from “Ghent Commissioners’ correspondence” to “claims of loyalists and British merchants.” Cross references lead to numerous other entries under such heads as “America,” “North America,” “Allied Forces,” etc. It is hoped that intending readers will be able as a result to identify classes of records likely to contain material relevant to their research. Lateral thinking is often necessary, and users of the Current Guide may need to accustom themselves to working from the general to the particular rather than vice versa. The index entry “United States of America: general correspondence,” for example, leads to three classes, FO 4, FO 5, and FO 371. The latter two contain numerous records about the Alaska boundary, including no less than sixteen volumes of papers in FO 5 alone which are devoted exclusively to this subject.

Some departments, such as the Foreign Office, the Admiralty, and the Treasury, have created detailed but complex means of reference to their own records. In addition, the PRO has compiled or acquired means of reference, generally called “class lists,” which describe the records, often very summarily, at the level of the piece. Sometimes this information consists of no more than a date or a bandwidth of file numbers. Researchers are advised that the work merely of identifying the particular documents they wish to read can be time-consuming, particularly if it is necessary to use original departmental means of reference, and they are strongly recommended to allow time for this preliminary work when planning visits to the PRO. Such advance identification of documents cannot be carried out by the staff of the PRO. A set of the class lists of records held at Kew (see below) has also been published on microfiche and may be available at major libraries in the United States.

Assuming that many American historians that come to the Public Record Office will be interested in researching records pertaining to America, the principal sources in the PRO are likely to be the records of those departments responsible for the conduct of Britain’s relations with America. For the period before 1783 and for matters which had a direct bearing on Britain’s remaining colonial interests in North America after that date, records have come to the PRO via the Colonial Office. From 1783 onwards, British-American relations have been conducted chiefly through the Foreign Office. Among Foreign Office records, the most frequently consulted classes are the above-mentioned original correspondence—i.e., the despatches sent to the Foreign Office in Whitehall by British ambassadors in Washington. American ambassadors in London, and others, with drafts of Foreign Office replies and internal Foreign Office minutes. Sorely neglected are the archives of the British embassy in Washington (PO 115) and of British consulates across America. which often give an “on the spot” perspective missing from the Whitehall papers. Similar classes of original correspondence and of embassy and consular archives survive in respect to most countries with which Great Britain has conducted diplomatic relations. Much can be gleaned about Britain’s attitude to American foreign policy from a study of such records relating to areas in which the two countries clashed or coincided: Mexico, Hawaii, Colombia, the Western Pacific, the Philippines, Palestine, the West Indies…. Other classes of Foreign Office records such as confidential print (papers printed for circulation within government); archives of boundary, claims and other commissions; treaties and maps, are all underused sources.

Records which accrued in the offices of governors and other colonial officials remained in the country concerned after independence: inquiries concerning such records should be addressed in the first instance to the National Archives, Washington, DC or Ottawa as appropriate, or to the respective state archives.

An article such as this can only hint at the range of other records of American interest in the Public Record Office. Some useful, if not up-to-date, reference works are:

- M. Andrews, Guide to the Materials for American History to 1783 in the Public Record Office (2 vols., Carnegie Institution, Washington, 1912).

- Charles O. Paullin and Frederic L. Paxson, Guide to the Materials in London Archives for the History of the United States since 1783 (Carnegie Institution, Washington, 1914).

- John W. Raimo (ed.), A Guide to Manuscripts relating to America in Great Britain and Ireland (Oxford, 1979).

- The British Public Records Office: History, Description, Record Groups, Finding Aids and Materials for American History, with special reference to Virginia (Richmond, Virginia, 1960).

More recently transferred records, not described in any of these guides, include records of the Admiralty, the War Office, the Air Ministry, and the Ministry of Defence relating to all aspects of British-American military cooperation during the Second World War and subsequently—including the Korean War, American bases in Britain and in British territories overseas, intelligence papers of the United States Army Air Force, and so on. The records of the Cabinet Office and the Prime Minister’s Office reflect British policy towards America at the highest level. Those of the Treasury include much information about financial negotiations, Marshall Plan aid, and economic cooperation. Among other bodies whose records contain much about America are the British Council, the British Food Mission, the British Purchasing Commission, the Children’s Overseas Reception Board. and the Anglo American Committee of Enquiry on Palestine.

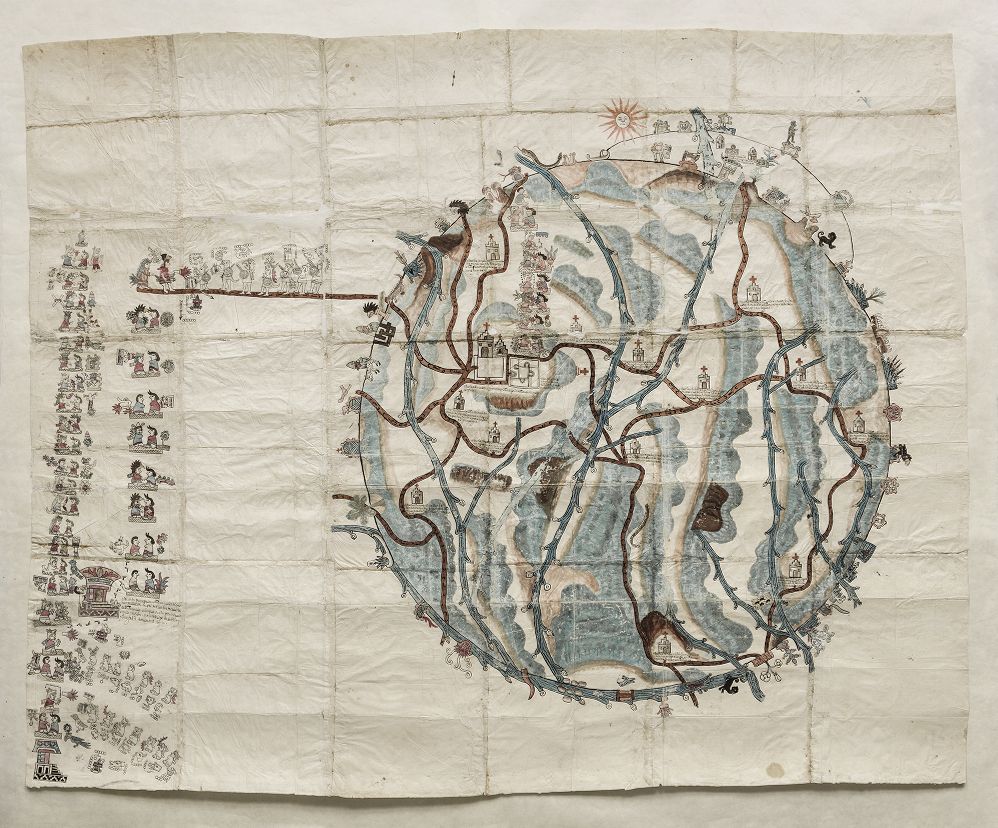

The PRO holds a large and significant accumulation of maps and plans, the majority of which have not been cataloged. Many maps of all or part of the American continent are described in P.A. Penfold (ed.), Maps and Plans in the Public Record Office 2. America and West Indies (London, HMSO, 1976), while others described in the supplementary card catalog in the Map Room at Kew. Maps of the United States in the PRO are consulted for purposes as varied as the investigation of international boundaries, the restoration of historic buildings, and the study of Amerindian place names.

Of course, all of the above information is on the fallacious assumption that American historians are interested only in America!

The Public Record Office operates in accordance with the provisions of the Public Records Act 1958 as amended by the Public Records Act 1967. Under the Public Records Acts, records are normally made available to the public thirty years after the end of the year of the last entry or paper on the file. Thus, records with no entries later than 1961 will become available in January 1992, and so on. Departments may, however, apply to the Lord Chancellor for certain records to be closed to the public for periods either less or greater than thirty years. Entended closure, usually of fifty or seventy-five years, is used for three broad categories of records: those whose disclosure might endanger national security; those containing information given in confidence, the disclosure of which would constitute a breach of faith; and those containing information about individuals, the disclosure of which would cause distress to or endanger living persons or their immediate descendants.

The holdings of the PRO are divided between two sites. The original nineteenth-century building in Chancery Lane (central London) houses the records of medieval administrations, the majority of the records relating to home and foreign affairs before 1782, and legal records of all periods. Records relating to colonial affairs, together with records of modem government departments, are now in the PRO’s modern building at Ruskin Avenue, Kew, Surrey, easily reached by Underground from central London.

A single reader’s ticket gives admission to both buildings. Before being issued with a reader’s ticket, intending readers are required to furnish positive proof of identity (a passport or national identity card in the case of non-British nationals) and to sign an undertaking to keep the rules for conduct in the reading rooms. The Of fice is open 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Mondays to Fridays, except for public holidays and two weeks closure for stocktaking at the beginning of October each year. We look forward to seeing you.

Geraldine Beech is head of the Search Department, Public Record Office, in Kew, England.