As a child, I always enjoyed watching Eyes on the Prize on PBS during Black History Month. I was fascinated both by the history of discrimination and the courageous efforts of young people to fight back against what seemed like insurmountable odds. The images of young children in Birmingham being sprayed by water hoses during peaceful protests, college students rising up on their campuses, and students desegregating schools inspired me. From participating in sit-ins to freedom rides to efforts to desegregate schools, students were on the frontlines of many of the civil rights protests. Even when they weren’t directly involved in the movement, the deaths of young people—Emmett Till in Mississippi, four girls in Alabama—helped spark or re-energize the Civil Rights Movement.

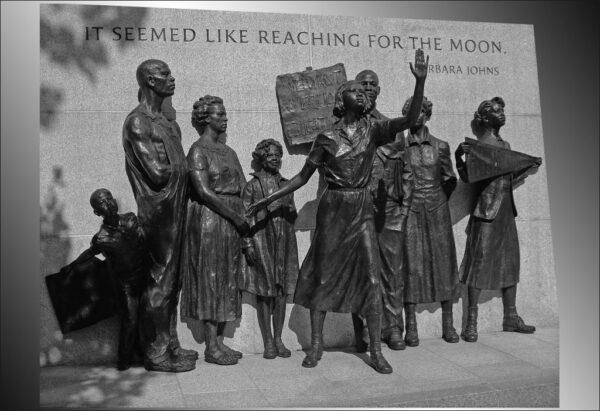

Historically, the leadership and activism of young people like Barbara Johns, captured here in the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial in Richmond, have helped improve access to education and civil rights for minorities. Ron Cogswell/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

As I got older and completed my undergraduate and graduate studies, I learned more about how and why these student protests came to be—the organizing that took place, the variety of causes involved, and the diversity of participants. In 1951, for example, a 16-year-old student named Barbara Johns led a boycott protesting overcrowding at her school in Prince Edward County, Virginia. Her efforts culminated in Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, which later became one of the Brown v. Board of Education cases. When segregation continued in many southern districts despite the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, black high school students, particularly after Freedom Summer in 1964, organized and demanded desegregation, a better education, voting rights, student rights, and an end to police brutality in Mississippi and throughout the South.

In fact, high school activists worked nationwide to improve their conditions. Whether they organized on their own or were guided by adults in organizations like the NAACP, SNCC, SCLC, CORE, Brown Berets, SDS, Young Lords, Young Patriots, or Black Panthers, they helped transform the society and their schools. Most prominent among these were boycotts organized by students at their high schools protesting disciplinary policies, overcrowding, ineffective school leadership, and lack of relevant curriculum.

In 1968, for example, Chicago high school activists conducted city-wide “Black Monday” school boycotts for three weeks straight. These protests led to leadership and curricular changes, but these partial successes came at great cost to many of the student leaders—some were suspended, expelled, and arrested; a few had to finish their education elsewhere. Black and Latino students in Los Angeles, Kansas City, Iowa, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, New York, Crystal City and Houston, Texas, and Philadelphia and York, Pennsylvania, participated in boycotts (walkouts or blowouts) for desegregation, community control of schools, and better curricular options, among other issues. They were fundamentally interested in acquiring a better education and helped transform individual schools and districts.

Today, students have continued to protest, both inside and outside of schools. High school students throughout the country have participated in immigration marches and in the Black Lives Matters campaigns. In Portland and elsewhere, students boycotted schools during and after Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. They refused to sit by idly as the presidential candidate used Islamophobic, anti-immigrant, and other discriminatory rhetoric. For issues within schools, students protested against a sanitized curriculum and the end of Mexican American Studies in Arizona, and against attempts to water down US history in Jefferson County, Colorado. In Chicago, student activists participated in campaigns against school closures, inadequate funding, and privatization. Seattle students walked out to bring attention to police brutality, and New York students boycotted standardized testing. Student activism is also alive and well on college campuses around the country, most notably at the University of Missouri.

The horrendous events at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, on February 14 differed from previous mass shootings as students organized walkouts and boycotts. Many young people have witnessed mass shootings during their lives, book-ended by the shootings in Columbine in 1999 and Parkland last month. For them, it is no longer acceptable to continue listening to adults frame the discussion of mass shootings around mental health or terrorism. Students, particularly those who lived through the tragedy in Parkland, are fed up with the lackluster and inept responses of lawmakers around gun control. Student activists have developed a multi-pronged strategy: weaken the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) ties with companies that provide NRA member discounts, and organize local and national student walkouts, boycotts, and marches.

Students of the past transformed higher education, curriculum, and leadership in K–12 schools, and energized Civil Rights and other movements that dismantled the legal vestiges of Jim Crow. Like so many other students in American history, and for that matter world history, the students in Parkland recognize that they are in a position to remove seemingly insurmountable obstacles. The history of student activism tells us that they are right to believe that they can effect change and that they have a chance to be successful.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Dionne Danns is associate professor at Indiana University Bloomington. She has authored or co-edited three books: Something Better for Our Children: Black Organizing in Chicago Public Schools, 1963–1971; Desegregating Chicago’s Public Schools: Policy Implementation, Politics, and Protest, 1965–1985; and Using Past as Prologue: Contemporary Perspectives on African American Educational History.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.