A satirical article in the Onion recently manufactured an AHA report that warns, “The past is currently expanding at an alarming rate” and “is larger now than it’s ever been before.” After laughing at this undeniable but ludicrous assertion, those of us at the AHA who attended many of the annual meeting digital sessions realized that the ridiculous urgency of this article was reminiscent of an equally alarming trend that historians truly are concerned about: the staggering abundance of data in the digital age.

The first annual meeting panel, “Are We Losing History?: Capturing Archival Records for a New Era of Research,” dealt with this problem head-on. Paul Wester of the National Archives and Records Administration discussed the declassification and archiving of government records, stressing the importance of striking a balance between keeping the records of most use to historians and acknowledging that not everything can be preserved. According to Matthew Connolly of the London School of Economics, the digital materials NARA would need to examine in order to work through its current backlog include “trillions” of e-mails and tweets; it would take “two million archivists working full-time for a year to catch up on processing the recent ‘Big Bang’ of record production.”

Anthony W. Marx, President and CEO of the New York Public Library, speaks at the plenary session. To his right, chair Stanley N. Katz (Woodrow Wilson Center), and speakers Joan Wallach Scott, Elliott Shore (Association of Research Libraries), and Michael Kimmelman. Credit: Marc Monaghan

Acknowledgment of this information crisis loomed large at other digital history panels as well. In his talk during the session “Text Analysis, Visualization, and Historical Interpretation,” Ian Milligan argued, “You cannot do justice to the 1990s and beyond if you do not consider the World Wide Web.” As this session practically burst at the seams with Twitter-savvy historians, Milligan’s words quickly resounded in a series of tweets, retweets, and favorites—generating yet more records for us to worry about keeping track of in coming years.

The challenges of the digital age arose even in sessions that were not focused on explicitly digital topics. The plenary session, “The New York Public Library Controversy and the Future of the American Research Library,” frequently acknowledged the influence of the digital age on collections management and the challenges that the ever-growing mass of information—both physical and digital—present to librarians. Joan Wallach Scott of the Institute for Advanced Study referenced some libraries’ increasing inclination toward digitization in light of “shrinking shelf space.” According to New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, “the library is the most evolving building typology today”—evolving because of libraries’ new inclusion of social spaces and computer labs in addition to bookshelves. These comments highlight both the overwhelming amount of information and the changing nature of that information.

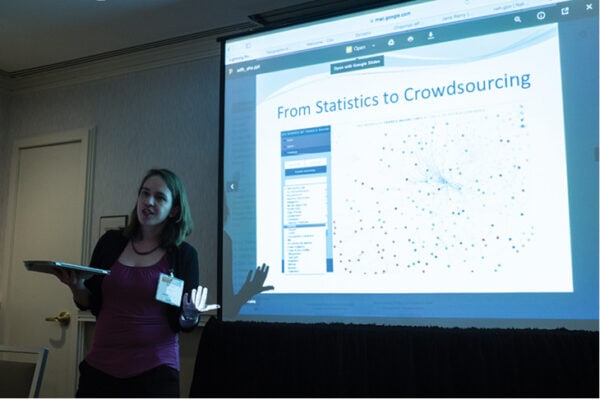

Jessica Marie Otis demonstrates Six Degrees of Francis Bacon at the Digital Projects Lightning Round. Credit: Marc Monaghan

It was not only archivists, visually inclined academics, and librarians who worried about the new challenges the digital age presents. Questions around producing scholarship in an increasingly digital environment arose, inviting input from publishers who debated open access (as in “Innovation in Digital Publishing in the Humanities”) as well as graduate students and early-career academics who discussed the recent controversy surrounding dissertation embargoes. With the availability of open-access publishing, history PhD candidates must make the decision about whether to publish their dissertations online upon graduation. While reflecting on the panel “Choosing to Embargo? What to Do with Your History Dissertation” in a recent blog post for AHA Today, PhD candidate Michael Hattem examined the risks that online access to a dissertation presents for future publishers of any resulting monograph. He also outlined the opportunities that the Internet provides for those who do not embargo their dissertations; for example, discoverability is a commonly cited benefit of making one’s dissertation available online. Hattem argued that “there were more effective ways of developing an awareness of one’s work than simply making the dissertation available for download on a university server”; he cited “use of social media, blogging, podcasting, and participation in various history projects (digital and otherwise)” as excellent alternatives. Ultimately, historians must take the time to understand the digital environment so that they can decide for themselves how best to weigh potential hazards against the opportunities that this environment presents.

As Seth Denbo anticipated in his November Perspectives on History article on the panoply of digital sessions, this year’s digital offerings prompted historians to push the boundaries of what has hitherto been considered “digital history”: “While not every historian is ‘digital,’ these methodologies have penetrated all areas of historical practice and are available to any historian.” It was not only the variety of subject areas, however, but of approaches historians were taking toward tackling the digital age that characterized these sessions. During a workshop, Kalani Craig advised historians, “Your curiosity should drive your tool use.” As there are a multitude of individual curiosities, then, so there should be a multitude of ways of doing digital history. This multitude was particularly evident in the digital pedagogy and digital projects lightning rounds. In this format, presenters gave brief presentations—one to five minutes each—in swift succession, enabling attendees to see samples of a large number of projects. For instance, during the Digital Projects Lightning Round, Roger L. Martinez used an animated geo-visual recreation of the medieval Spanish city Plasencia to present details of medieval life that are vital to understanding the interaction of different religious groups at the time. Shortly thereafter, Jessica Marie Otis presented The Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, a project that, according to Otis, “reconstruct[s] the social network of early-modern Britain through a combination of statistical analysis and crowdsourcing.” And only a few minutes later, Rachel Deblinger gave attendees a tour of Memories/Motifs, a multimedia archive that takes users on a tour through 1940s and ’50s American “memory creation” relating to the Holocaust.

Surrounded by colleagues, historians Jesse Stommel and Kathryn Tomasek live-tweet the Digital Pedagogy Lightning Round. Word travels fast in digital history. Credit: Marc Monaghan

The proliferation of digital cultural materials in all areas of study calls for the participation of many in digital history; thus, it was appropriate that this year’s annual meeting also be characterized by openness, accessibility, and community. To invite historians to learn more about digital methods, the meeting commenced with the Getting Started in Digital History workshop, which offered beginner and intermediate tracks in a variety of topics. Historians could learn about data management, digital pedagogy, visualizations, and much more. The annual meeting concluded with THAT Camp, hosted by The New School, which offered similar opportunities for beginning and advanced digital historians to mingle. Participants proposed sessions in the morning on subjects they wished to discuss and learn more about. The Twitter workshop Caleb McDaniel led, for example, was attended by both seasoned tweeters and those who had no tweeting experience at all. I was delighted to find that I could, in the same session, help a fellow historian change his username while I learned to create Twitter essay chains.

We live in a time when scholars increasingly turn to the web in their research, when most new data is born digital, and when the Internet offers an ever-growing number of platforms for online publication and expression. That ever-expanding past has gone digital, and as historians each of us must step up our game if we are to calm the Onion’s nerves.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.