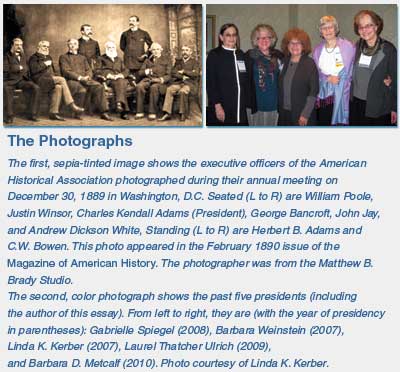

The Report of the AHA Committee on the Status of Women, the “Rose Report,” was published 40 years ago this fall. The report, along with the survey on which it was based, provides a baseline for considering issues of gender within the historical profession. The next issue of Perspectives on History will carry an article marking the report’s anniversary. In this column, I want to offer some personal reflections of my own, both about women in the historical profession in particular and about the gendered transitions across the generations more generally. I was spurred in part by the color photograph above taken in San Diego last January. The occasion was a gathering of the current and past presidents of the Association who, for the last few years, have gathered informally on the evening before the scheduled events of the annual meeting. The picture shows the Association’s last five presidents, all women. As the last of the quintet, I didn’t want to let this remarkable sequence pass without comment.

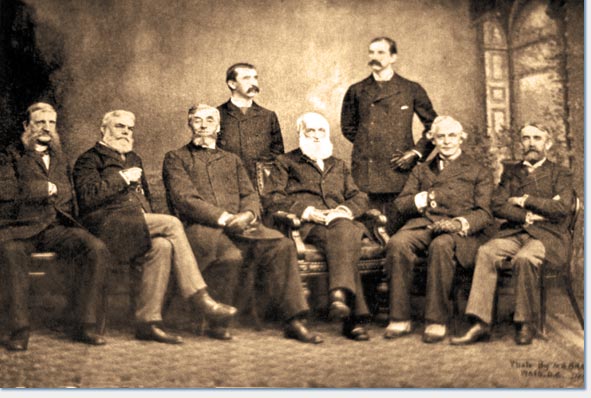

I thought of this photograph when I subsequently had occasion to check the Wikipedia entry for the AHA, which features a photograph (reproduced here) of the original executive committee of the AHA. As befits its time, that committee was composed only of men.1 Obstacles and inequities for historians—and not only in relation to gender—still remain, but the two photographs do illustrate one dimension of our changing face as a profession. I thought of this contrast again a few weeks back when I signed 48 certificates, only 3 of them for women, honoring 50-year members of the AHA, trying to imagine the world of historians in 1960, before the vast expansion in higher education of that decade and before the percentage of professional women historians went much beyond single digits—only 14 percent in academic employment even by 1980.2

I thought of this photograph when I subsequently had occasion to check the Wikipedia entry for the AHA, which features a photograph (reproduced here) of the original executive committee of the AHA. As befits its time, that committee was composed only of men.1 Obstacles and inequities for historians—and not only in relation to gender—still remain, but the two photographs do illustrate one dimension of our changing face as a profession. I thought of this contrast again a few weeks back when I signed 48 certificates, only 3 of them for women, honoring 50-year members of the AHA, trying to imagine the world of historians in 1960, before the vast expansion in higher education of that decade and before the percentage of professional women historians went much beyond single digits—only 14 percent in academic employment even by 1980.2

Changes in women’s participation in the historical profession are, of course, part of the larger transition in women’s representation across professions and in women’s employment outside the home generally. Those of my generation invariably have stories about earlier cultural attitudes toward women professionals that for younger historians—men or women—seem unbelievable. My immediate predecessors writing in this column have drawn on their own experiences to depict the difficulties women scholars faced. Gabrielle Spiegel wrote about the efforts women often exercised three or four decades back in compartmentalizing even pressing responsibilities related to family.3 Laurel Ulrich recounted her experiences with the presumption that a woman, especially a woman with children, did not really want or need a job—no question of why she had devoted years of work to securing the credentials to get one.4 Barbara Weinstein recalled the implicit assumption prevalent in her graduate years that any historian could readily relocate for research or writing opportunities, while none of her mentors “felt that they should advise me to avoid entangling alliances or refrain from having children.”5 In my own case, in my first job, the department chair, in an unguarded moment in those less-litigious times, filled me in on why the department, geared to do so, had opted not to vote on the issue of my tenure. “Think Mary Douglas,” he said. “To even imagine a woman who would leave her family to commute to work is simply taboo.” For the anthropologist Douglas the term “taboo” labeled whatever did not fit neatly into society’s classifications and therefore was imagined as either holy or dangerous—clearly, with a rhetorical flourish, the latter being suggested here.

Changes in women’s participation in the historical profession are, of course, part of the larger transition in women’s representation across professions and in women’s employment outside the home generally. Those of my generation invariably have stories about earlier cultural attitudes toward women professionals that for younger historians—men or women—seem unbelievable. My immediate predecessors writing in this column have drawn on their own experiences to depict the difficulties women scholars faced. Gabrielle Spiegel wrote about the efforts women often exercised three or four decades back in compartmentalizing even pressing responsibilities related to family.3 Laurel Ulrich recounted her experiences with the presumption that a woman, especially a woman with children, did not really want or need a job—no question of why she had devoted years of work to securing the credentials to get one.4 Barbara Weinstein recalled the implicit assumption prevalent in her graduate years that any historian could readily relocate for research or writing opportunities, while none of her mentors “felt that they should advise me to avoid entangling alliances or refrain from having children.”5 In my own case, in my first job, the department chair, in an unguarded moment in those less-litigious times, filled me in on why the department, geared to do so, had opted not to vote on the issue of my tenure. “Think Mary Douglas,” he said. “To even imagine a woman who would leave her family to commute to work is simply taboo.” For the anthropologist Douglas the term “taboo” labeled whatever did not fit neatly into society’s classifications and therefore was imagined as either holy or dangerous—clearly, with a rhetorical flourish, the latter being suggested here.

Many of us have also commented on certain kinds of advantages women of earlier decades in some cases enjoyed. The assumption that at a practical level women didn’t need, or at least might not expect, a job was in some ways true for those whose spouses had regular employment at a time when dual-career families were less common. Indeed, that expectation, internalized, may have made it possible for some women to follow less conventional but very productive lines of research or work—why not, if no job was at stake? This independence was, as Laurel Ulrich wrote, a dimension of “the advantage of disadvantage.” In my case, it let me forge ahead despite the advice of the chair of my graduate department in the late 1960s: “You can’t possibly work on Muslims in India—they simply don’t matter.” (Male or female, we all remember conversations like these when we are on the receiving end and can’t imagine what we in turn may have said to students or junior colleagues but now fail to remember.) As affirmative action concepts and programs grew and percolated into a wide range of institutions, moreover, some women, myself included, benefited from employment or other opportunities intended to increase diversity.

Cultural and legal changes in regard to sexism—the issue at stake in many of these personal anecdotes—have made a difference. Last month’s Perspectives on History included a column by the current co-presidents of the Coordinating Council for Women in History, an AHA affiliated society with a dual mandate of increasing the participation of women in the historical profession as well as encouraging the field of women’s history.6 Their essay charts this considerable success, noting that the proportion of new doctorates awarded to women is now over 40 percent.

There are however, as they and others note, many reasons to sound a caution. In a memorable talk at the Annual Meeting breakfast organized by the Committee on Women Historians in 1998, Lynn Hunt asked whether the increased number of women in the profession—its “feminization”—risked lower pay and less respect for history and the humanities generally, an issue still important given the persistence of stereotypes about gender and about what constitutes “soft” subjects.7 Robert Townsend, to whom we are always in debt for his careful tracking of trends among historians, noted in his recent report on women historians in academic positions that the percentage of women in academic employment continues lower than that of other humanities disciplines, a pattern clearly evident although its explanation is not.2 For women generally, however, as Linda Kerber, first of our quintet, recently wrote, real equity in history or any other line of work will not be achieved till issues entailed in raising children are squarely addressed.8

A column by David Leonhardt this past month in the New York Times discussed a survey of business school graduates showing women and men equally successful in business professions until, he argued, family responsibilities and full or partial withdrawal from paid employment intervened.9 The comments on his article rehearsed complex, albeit familiar, themes about issues like choice and “innate” gender-specific behavior. Leonhardt had in fact made two points relevant to such responses. The first was the impact of even modest changed expectations about male parental roles. The second was the limitations on choice when state policy does not support childcare or “family-friendly” policies, only haltingly in place at the state level in a few places in the U.S. According to Leonhardt, the United States is the only rich country that does not provide some amount of paid parental leave; and countries like the United Kingdom, in addition, now provide all workers the formal right to request part-time work. Apart from official policy, of course, workplace policy matters a great deal as well. Leonhardt emphasized the importance of part-time schedules, scheduling flexibility, and opportunities to withdraw and return to the workplace, practices that some professions in this country have pioneered.

The web pages of the Committee on Women Historians, a standing committee of the AHA, provide links to the impressive documents produced under the auspices of the committee, the Association’s Professional Division, and the AHA generally, addressing gender equity. These include “Best Practices” statements on gender for the academic workplace (2005) as well as one for public history settings (2006). A significant theme running through the documents is the one noted at the outset by the Rose Report, namely that “best practices” are critical not only to women’s interests but to the health of the profession generally. In the words of the Rose Report, “Our study has convinced us that many, though not all, of the problems of women in academic life are reflections of general problems affecting men as well as women, and it is our belief that most of our recommendations would serve to provide a more liberal, encouraging, and progressive atmosphere for all students and teachers of history.” Linda Kerber entitled her comment when the latest “best practices” statements were issued “The Equitable Workplace: Not for Women Only.”10

Issues that may benefit women—mentoring, transparency in hiring and promotion, spousal hiring policies, awareness of implications of service assignments, and, indeed, family-friendly policies—make for a higher quality and more humane working environment over all. At this year’s June AHA Council meeting, one item for discussion was childcare (at the annual meeting of the AHA). The issue was raised by one of our standing committees, but not the Committee on Women Historians; rather it came from a generationally defined committee, the Graduate and Early Career Committee. Gains in forms of diversity other than that of gender, it is important to add, have been severely limited for the historical profession, and there, too, attention to the kind of best practices noted above is critical.

Such practices enhance working relationships among employees of different generations (“mature,” “boomer,” “X,” “millennials” and so forth) as well. With longer life spans and delayed retirement, a workplace these days may well include individuals who have developed radically different cultural attitudes about work and life than those of other generational cohorts. Inclusive practices like transparency and mentoring that serve diversity help bridge these differences too. The very title of a panel organized at last year’s annual meeting—“What Generations of Historians Learn from One Another”—emphasized not only the gains but the cultural and intellectual challenges when historians of different ages interact.

Such practices enhance working relationships among employees of different generations (“mature,” “boomer,” “X,” “millennials” and so forth) as well. With longer life spans and delayed retirement, a workplace these days may well include individuals who have developed radically different cultural attitudes about work and life than those of other generational cohorts. Inclusive practices like transparency and mentoring that serve diversity help bridge these differences too. The very title of a panel organized at last year’s annual meeting—“What Generations of Historians Learn from One Another”—emphasized not only the gains but the cultural and intellectual challenges when historians of different ages interact.

Photographs like the ones included here can only tell us so much. What is the level of collegiality and fairness in any of our given workplaces? The call for a more equitable and humane workplace arguably needs even more, not less, attention now when economic conditions have had such a negative impact on the working conditions of historians and others in educational and public history settings. Scrupulous attention to collegiality, transparency, scheduling flexibility and ingenuity, imaginative generosity, and the long view for supporting each other, cannot solve institutional problems that need to be addressed at many levels.11 But “best practices” like these matter a lot.

Notes

- At https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Historical_Association. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “What the Data Reveals about Women Historians,” Perspectives on History, May 2010. [↩] [↩]

- Gabrielle M. Spiegel, “History Mom,” Perspectives on History, October 2008. [↩]

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “The Trouble with History,” in Perspectives on History, December 2009. [↩]

- Barbara Weinstein, “Historians and the Mobility Question,” Perspectives on History, February 2007. [↩]

- Nupur Chaudhury and Barbara Ramusack, “The Coordinating Council for Women in History: Accomplishments and New Goals,” Perspectives on History, September 2010. [↩]

- Lynn Hunt, “Has the Battle Been Won? The Feminization of History,” Perspectives, May 1998. [↩]

- Linda Kerber, “Equity for Women—Still,” The Chronicle Review, 29 August 2010. [↩]

- David Leonhardt, “A Labor Market Punishing to Mothers,” New York Times, August 3, 2010. [↩]

- Linda K. Kerber, “The Equitable Workplace: Not for Women Only,” Perspectives on History, February 2006. [↩]

- My phrase “scheduling ingenuity” is inspired by the suggestion in Barbara Weinstein’s piece cited above (in note 5) proposing strategies for including less mobile scholars in the work of residential research centers. [↩]