Editor’s Note: The following essay is based on the author’s presentation in a session at the annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians held, in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 2010. A version was previously published on the AHA blog, AHA Today.

Looking at the data about the status of women in the history profession provides conclusive evidence that statistics may not lie, but they rarely tell the whole truth. The numbers let us chart the very slow progress of women in the discipline, but they do a poor job of explaining why women are underrepresented at every level in academia. What the data does tell us is that even as the rest of academia has moved toward greater balance in the representation of women, history has lagged well behind most of the other fields.

Figure 1

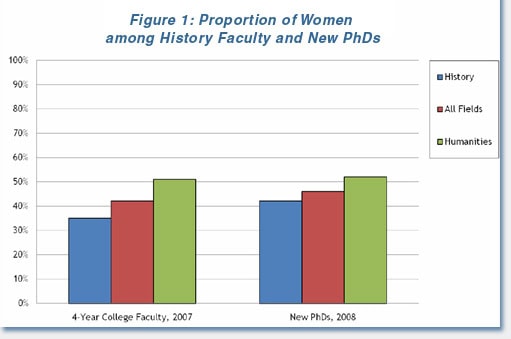

This is clearly evident in the latest snapshots of data we have for faculty and new PhDs. Surveys of four-year college and university faculty in 2007, for instance, found that women comprised just under 35 percent of all history faculty (Figure 1). This compares to 42 percent of the faculty in all fields, and 51 percent of the faculty in the humanities.

History was slightly closer to the norm in conferring new PhDs, as 42 percent of the last two cohorts of history PhDs were women. But this proportion still falls below the average for all disciplines, 46 percent, and well behind the humanities as a whole, where women receive 52 percent of the degrees.

Proportion of Female Faculty in Disciplines 1980 to 2007

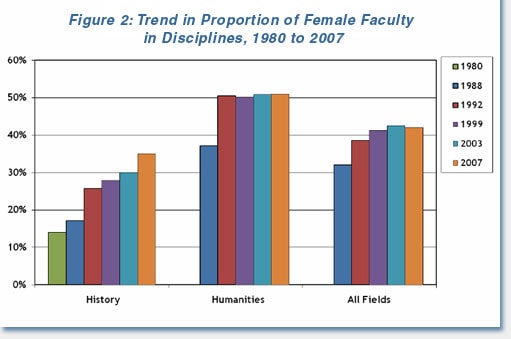

While these numbers are ample cause for concern in the discipline, the trend over time does show some modest gains. Thirty years ago, women accounted for just 14 percent of the faculty in history departments (Figure 2). While we lack comparable data that far back for the other disciplines, figures from 1988 indicate just how far behind history must have been. As recently as 20 years ago, the representation of women in history was half the representation of women in all academic disciplines—with women accounting for 32 percent of all faculty in higher education, and just 17 percent in history.

Figure 2

The sharp growth among all disciplines in the 1980s and into the early 1990s suggests the effects of active affirmative action programs following the Bakke decision. But as can be seen, the growth in the representation of women in the humanities peaked at 51 percent in the early 90s, while the representation of women in all disciplines peaked at a little over 40 percent a decade ago. In contrast, history continues to make progress, even if it still falls short of the rest of the academy.

Despite the evidence of recent modest improvements among faculty teaching the discipline, history now faces some significant impediments to further growth. The problems start with the students attracted to history. Over the past 20 years history has graduated some of the smallest proportions of female undergraduates of any field in higher education—well below all of the other humanities and social science disciplines outside of religious studies.

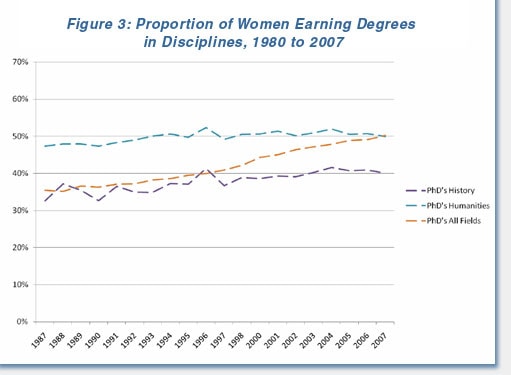

And unlike the trends among faculty, these numbers are relatively unchanged over the past 20 years. As can be seen in Figure 3, at the undergraduate level, women earned only 37 percent of the undergraduate history degrees in 1987, and two decades later their representation had grown to just 41 percent. In comparison, over that same span there was a significant shift in the representation of women earning undergraduate degrees in all fields, growing from 52 to 57 percent of the degrees conferred in 2007. This makes the traditionally large representation of women in the humanities seem like the new normal.

Figure 3

The trend among those earning history PhDs is similar to the trend among those earning undergraduate degrees, demonstrating the close connection between the two stages in the academic pipeline. In the history discipline, the representation of women among new PhDs has been relatively static over the past decade, hovering right around 40 percent of the new doctorates conferred.

Here again history is strikingly different from the other disciplines (Figure 3). The representation of women among new PhDs in the humanities and among all disciplines is again converging, this time at just over 50 percent of the new degrees conferred.

The most troubling aspect of the trends in female student enrollment and graduation is the way history has plateaued at both the undergraduate and graduate level. If women continue to earn barely 40 percent of the degrees in history, that seems to set a rather hard ceiling for the representation of women among those employed in the discipline. It seems exceptionally difficult for the discipline to approach parity in the employment of women without changing some of the dynamics that seem to drive women away from study in our subject.

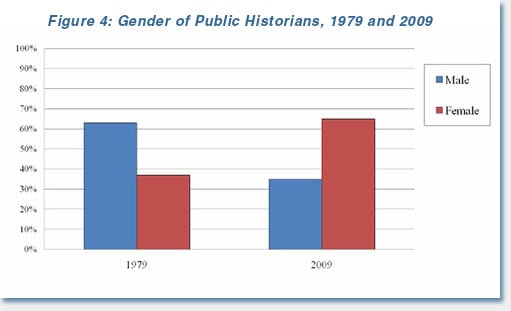

That said, there is at least one important counterexample to this reading. One of the most striking findings in our recent survey of public historians is a dramatic shift in the proportion of women among historians employed outside of academia.

Gender of Public Historians

Our recent survey of public historians found that two-thirds of them were women (Figure 4). This marked a dramatic change from 30 years ago, when women comprised barely a third of the population of public historians. Note that even at 34 percent of the public historians back in 1980, their representation was still double the figure among historians in academia. As we move to the present, the gender balance is almost reversed. And once again, the representation of women among public historians is still nearly double that of historians in academia. What the data cannot tell us is why women find better employment outside of academia than within, and why women are so heavily represented in public history relative even to their representation of women among those earning degrees. The data does suggest, however, that it may not be the discipline of history itself that is at the root of gender disparities, but rather that it could be the structure or culture of history departments.

Figure 4

Unfortunately there is very little recent data on such things as salaries and mobility within academia, which might give us better insights into the structural problems in academia. The most recent available data is from 2003, but it does offer some modestly positive news, suggesting very little difference between the average basic salaries for male and female historians at colleges and universities. On average, women at the full and associate professor level earn between one and two and a half percent less than their male counterparts, while women at the assistant professor level were earning an average of one and a half percent more than men.

But when income from other sources (royalties, lecture and consulting fees, and the like) is included, it becomes clear that male historians earn significantly more in outside income than their female counterparts. There is a difference of about $6,000 a year at the full professor level and about $2,000 for assistant professors. But this expands the average total income for men to between 7 and 10 percent higher than their female counterparts at each rank.

The most difficult and contested area of academic employment is at the associate professor level, where it is widely noted that many women end up stuck in positions with tenure but with little prospect for further career advancement. As you can see from the broad numbers, women are, in fact, slightly overrepresented at the associate professor level—accounting for 36 percent of the faculty at the rank, as compared to just 18 percent of full professors and 32 percent of the assistant professors. But the underlying data offers a rather confused picture on this. In 2003, male associate professors had been at that rank for a little over eight years, while women had been at that level for six. That is, the one really substantial survey available does not provide clear evidence of women actually being stuck at that rank. But there is ample evidence of the costs to many female associate professors—they are significantly more likely than their male counterparts to be single, divorced, and without children. And as a group, women at that rank were much more dissatisfied with their jobs, salaries, and authority to make decisions than their male counterparts.

So even without delving into the problem of so-called leaks in the pipeline, the data shows that there are fundamental problems from beginning to end. Obviously all these numbers and charts are derived from quantitative data, and cannot indicate the actual lived experience of members of the profession, but they do help to point to a number of unpleasant truths about the history profession and to the very modest gains women have made over the past 40 years.