I first became interested in history at age 10, when my family spent a year in England. Fascinated by seeing old buildings and coins, I began reading novels about Britain’s past. After returning to California, I turned to historical fiction about other places. In college, picking a class on ancient Greece was natural, since I loved Mary Renault’s novels. I had a chance to go to China, so I thought I would learn a bit about the place and enrolled in a Chinese history class. The trip fell through, but I was hooked on Chinese history—partly because the professor assigned a historical mystery novel.

Assigning novels set in the past alongside nonfiction helps to fill gaps in the historical record.

As historians, we are often asked how we became interested in history and our specific fields—in my case, Chinese studies. The preceding story is one of my responses. But as with all storytelling, I have highlighted some things and left others out.

Here is a different way I could tell the tale: I first became interested in history when I spent my fifth-grade year in England, and I became an avid player of Diplomacy, a game involving the period leading up to World War I. My fascination with the past was deepened by reading historical novels; watching films about historic events; and seeing plays set in the past, including one by Tom Stoppard featuring Lenin and James Joyce. I also watched television programs set in the past. I was addicted to Time Tunnel, a time-travel show, and Kung Fu, which focused on the life of a Shaolin monk in 1870s America with flashbacks to his earlier life in China. In my first Chinese history class in college, I was intrigued to encounter Daoist texts in a sourcebook that seemed familiar from my watching Kung Fu.

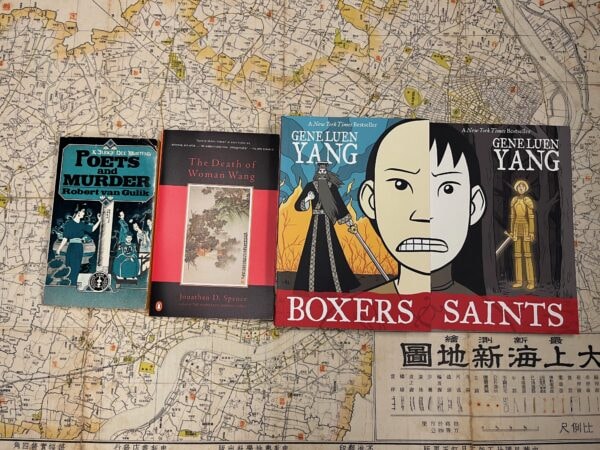

Both of these narratives are true, and taken together, they help explain my career path and why I’ve spent decades assigning historical fiction. I have had students read J. G. Ballard’s autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun in classes on Shanghai and Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel Boxers in courses on the world in 1900. In a course on comparative revolutions, students read The Underdogs, a fictional account of the 1910 Mexican Revolution written by Mariano Azuela in 1915. In undergraduate seminars on historical narrative, I use novels such as Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account and Janet Lewis’s The Wife of Martin Guerre. And when I teamed up with literary specialist Deidre Lynch to co-teach an interdisciplinary graduate seminar on history and fiction, our syllabus included a Walter Scott saga and a novella featuring Cecil Rhodes and a time machine.

Why assign historical fiction? Sometimes I want to fill a gap. For example, the anti-Christian insurgents who missionaries dubbed “Boxers” were illiterate, and we do not have a record of a confession by a Boxer. If I assign only nonfiction, students will not get a story told from a Boxer’s perspective. Yang’s Boxers gives them one.

I assign fiction to draw attention to the way all creators of historical narratives make decisions about plotting that have consequences.

Sometimes, instead, I assign fiction to draw attention to the way all creators of historical narratives make decisions about plotting that have consequences. In nonfiction and fiction alike, it matters, for example, where one begins and ends, and I have found it easier to get students to appreciate this when I bring in novels and films. Consider again the Boxers: they murdered Chinese Christians and missionaries early in 1900, but foreign soldiers sent to China to suppress them later committed atrocities. When I show the 1963 film 55 Days at Peking, I stress that the film ends before foreign soldiers leveled villages. I then refer to nonfiction books that do and do not, metaphorically, have the credits roll at the same point. We discuss the implications of the chronological choices involved.

When selecting fictional readings, I am generally drawn to authors who strive to do justice to the historical record and give voice to those left out of traditional top-down historical narratives. This explains why, as different as they are, I like The Moor’s Account (whose protagonist is a real person mentioned in passing in standard narratives of an expedition) and Boxers (whose protagonist is a fictional Chinese boy who became part of an anti-Christian group in 1900). Each is boldly imaginative, but the authors did research much like historians do. When Lalami graciously guested in my class, she gave eloquent answers to questions on method. At the end of his book, Yang references key scholarly works that he used to research his graphic novel. (He also wrote a companion book to Boxers called Saints, which focuses on the very different experiences of a fictional Chinese Christian girl during 1900 and is also good for classroom use.)

Sometimes I find pedagogic uses for top-down tales and works that show little concern for the historical record. These novels and films are ones I teach largely to criticize them for the liberties they take and what they reveal about the time they were created, and 55 Days at Peking is a case in point. Not only does this film have white actors playing key Asian roles (as did Kung Fu) and focus on elite figures, but it includes plot moves lifted from old westerns and Fu Manchu films.

Selecting fiction for a course depends on the kind of class I’m teaching. In survey courses, it is sometimes incidental whether a work is fiction or nonfiction and, if fiction, whether it is about the author’s present or past. Reading The Underdogs gives students a sense of events given short shrift in comparative works on revolutions. Had I discovered an engaging memoir written in 1910 about events as they took place, I may have chosen that instead. In Chinese history surveys, fiction can provide a window into a period before the author wrote it or to the era in which it was written. In other cases, though, I use memoirs or accessible academic histories written with flair (such as Jonathan Spence’s The Death of Woman Wang) to achieve the same result. In courses specifically about historical narrative, by contrast, style and genre are crucial. One goal I have in these classes is to work with students on teasing out the differences among works of fiction and nonfiction and those that blur the line, as Spence does when he imagines a dream his title character had just before dying.

I think strategically about pairing fiction and nonfiction readings—but different courses lead to different pairings.

I also think strategically about pairing fiction and nonfiction readings—but different courses lead to different pairings. In a Shanghai course, I might pair Empire of the Sun, which is written from the perspective of a British boy who lives a privileged existence in the city and then faces hardship, with fiction by a Chinese writer that deals with the same period. Through these books, students get a sense of how different a single historical setting can look through the eyes of different observers. In a course on historical narrative, by contrast, I might pair Empire of the Sun with the author’s autobiography, Miracles of Life. If I ever taught a French history class, I might assign either Lewis’s The Wife of Martin Guerre or Natalie Zemon Davis’s nonfiction work The Return of Martin Guerre. In a course on historical narrative, I once assigned both books and urged students to notice distinctions, like only Davis using phrases like “might have.”

I have focused on what I hope students will learn from my use of historical fiction, but I have learned a lot myself from teaching novels. I once thought, for example, that a clear difference between novels and nonfiction works was that only the latter had footnotes. But when teaching a graduate seminar led me to read my first novel by Scott, I saw it had footnotes by the author. When I stress to students that it is wrong to refer, as some do, to all books as “novels,” I do not mention footnotes. Instead, I focus on a concept I first came to appreciate while co-teaching that same class: the “unreliable narrator.” Fiction often has narrators we clearly should not trust. Historians strive to be narrators who readers can trust, even when experimenting. The Death of Woman Wang’s dream section has a fictional feel, but Spence sets it off in italics, a signal to readers that he is venturing into speculations.

I have learned not only from teaching historical fiction but also from trying here to explain my relationship to it. And doing so has left me with new questions to ponder. Why, I wonder now, looking back at the two stories I began with, each striving to present my personal history in the guise of a reliable narrator, have I assigned novels and films but never any of the plays or television shows that early on sparked my interest in history? Perhaps being assigned Tom Stoppard’s Travesties or episodes of Time Tunnel would play the same role in inspiring a first-year student to major in history that being assigned a Judge Dee mystery did for me at age 18.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor's Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine. He tweets @jwassers.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.