Readers open Perspectives on History expecting to find Robert Townsend’s comprehensive and agile presentations of data—all sorts of data, but most often relating to the employment of historians. If he is truly on his game in any given month there will be pie charts. Otherwise we settle for the less elegant bar graph, or perhaps a gracious curve or two illustrating a trend. Regardless of the medium, we learn. We learn about the vicissitudes of the academic job market for historians; the ups and downs of enrollments in history courses; and the trends in advanced degrees.

Not this time. This month Robert Townsend the historian, author of History’s Babel: Scholarship, Professionalization, and the Historical Enterprise in the United States, narrates the AHA’s journey toward the digital age, and the many bumps along the way. It is time for this story, because after 24 years at the AHA, Townsend is moving to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences where he will direct a new Washington office and oversee the Humanities Indicators project. He entered the AHA as an intern; he leaves as deputy director.

Townsend is also the right person to tell this story. He played a fundamental role in shepherding the AHA’s publishing program into the digital age, nudging the Association toward a publishing model that wed traditional print publications with an array of social media spaces, allowing multiple generations of historians to contribute to a single conversation across media platforms. He helped diversify the AHA’s engagement with the many professions that constitute our discipline, and facilitated what is today a thriving online community of historians. For that, as well as the pie charts and bar graphs, we are all grateful.

—James Grossman

It is easy to talk about a revolution; it’s rather more difficult to negotiate through one. When I started at the AHA in 1989, our publishing program consisted of three serial publications and a few dozen short monographs and study aids. For all practical purposes, it differed in size, but not in substance, from the Association’s publication program of a full century earlier. While I was hired because I had some experience with databases and could use a PC-one of the first purchased by the AHA-my job was to help get ink on paper.

As I leave the Association, the program seems fundamentally changed. While print publications still retain a central place, they are increasingly only one part of a much broader communications program for reaching members and a much wider public. More importantly, we now think in terms of a wide spectrum of interactions that go well beyond our membership. But it has not been a simple or easy journey, and we have discovered on more than one occasion that it is quite easy to extend past our audience.

My earliest attraction to electronic media flowed from the idea that the technology could open up new ways of telling history, and the AHA staff moved quickly to embrace the early promise of the web. Guided by Roy Rosenzweig at the Center for History and New Media, the AHA set up a web presence in fall 1994 comprised largely of content from Perspectives on History. However, despite my earnest—and quite naïve—insistence that the print version of the AHA’s flagship scholarly journal, American Historical Review, would soon disappear, it was almost five years before the AHA took the next hesitant steps toward that vision.

Anticipating that the online environment would facilitate new kinds of scholarship-scholarship that was fundamentally transformed by the medium and open to new kinds of arguments and interplay between analysis and evidence—the AHA finally partnered with a number of other organizations to create two new types of facilities for online publication. In 1999, working with the University of Illinois Press, National Academies Press, and Journal of American History, we helped establish and underwrite the History Cooperative, an online platform for history journals. Around the same time, we also partnered with Columbia University Press and Columbia’s libraries under a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to create the Gutenberg-e project, an innovative effort to convert dissertations into online scholarly monographs.

In my memory, both projects were among the most exciting and innovative I had the pleasure of working on at the AHA. And for a time, others in the humanities looked to these projects as models at the cutting edge. Ultimately, however, we discovered two rather serious problems-money and support from the field.

In retrospect, we rushed too far ahead of both the discipline and the available technologies. While trying to maintain a low subscription rate for both institutions and members, we could not pour sufficient funds into the projects to sustain them in the face of rapid technological change. And among our members, we struggled to secure authors who were interested in actually doing something new and innovative with the medium.

In a survey of members I conducted in 2010, I found that while almost 73 percent of academic historians were actively using new technologies in their work, most still saw history primarily as a medium of words, and hence of the printed page.1 That, I am afraid, is where we still stand insofar as innovation in the area of scholarship is concerned, and quite frankly the experience made me rather wary about getting too far ahead of the curve again.

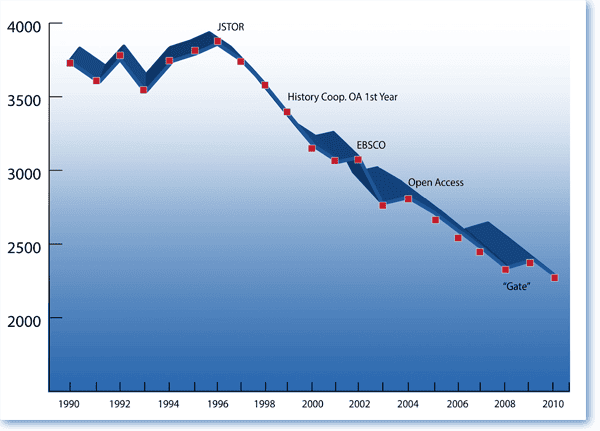

Figure 1: AHR Institutional Subscriptions (Print and Online), 1990 to 2010

And I am sad to say that part of our financial challenges seemed to arise from our experiments with open access, as the AHA has yet to find a happy balance between our revenue needs and our desire to reach the widest possible audience. Over the past 15 years, the Association experimented with a number of different types of open access in an effort to find that balance. In 1997, we revised all of the AHR author contracts to allow authors to post a copy of their article on a personal website or institutional repository, known as “self-archiving,” but only a handful of authors (mostly aligned with the digital humanities) took up the offer. Then, as we kicked off the History Cooperative in 1999, we made the issues completely open online. Unfortunately, institutional subscriptions fell 8.5 percent during the first year of the experiment (fig. 1).

To some extent, the subscription drop could be attributed to the journal’s availability on JSTOR. But the decline during the year of open access was notable as the largest annual drop in the time we’d kept records, so the Association closed access again to all but members and subscribers. In 2005, the AHA Council decided to experiment with a different form of open access-making all articles open immediately upon publication, but keeping the book reviews (which tend to hold the most immediate interest for readers) closed.

We quickly discovered that libraries did not share our sense of priorities about the journal’s content, as institutional subscriptions dropped again, and library buyers freely cited the open availability of the articles as the reason for dropping their subscriptions. After another decline of almost 18 percent in subscriptions, and as evidence arose that the audience for the articles was fairly limited (most readers left mere seconds after landing on an article), the AHA Council walked back a bit from the open access policy—first by adding a one-year gate to the articles, and then by shifting to a three-year moving wall. That decision again stabilized our subscription sales. We also revised the author agreements, and currently provide a toll-free link to the published articles that the author may post on their websites or in an institutional repository.

I recognize that many people view the elimination of print as key to solving many of the cost impediments to open access, but I have found very little interest in an e-only option among dues-paying members. In our internal surveys, and a separate survey of members of the National Council on Public History, well over 80 percent wanted the print version to provide their initial reading experience for the journal.2 Surprisingly, it seems there is very little difference between the age cohorts on this question. The technology has changed some behavior. Most members seemed perfectly willing to dispense with print after their initial reading, and rely on the digital version as an archive, but the print and digital forms are clearly serving two different needs—two needs history organizations ignore at their own peril.

As a result of past challenges, the AHA is moving more cautiously into the area of online scholarship, and is focused instead on engaging members and others more generally interested in history. We have been posting content from Perspectives on History since 1995 (mostly ungated). In 2006, we started the AHA Today blog, and followed that over the past five years with spaces on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter.

The print publications still serve as the centerpiece the communication program-feeding content online and setting up a variety of conversations across a range of social media sites-but recently, original content on the website and blog have begun to feed content back into our print publications.

As part of this change, the organization had to accept a significant internal cultural shift. When I first took over as “editor” of Perspectives in 1992, my role was nominal-largely limited to placing text on the page. That narrow view of communication is no longer viable. Being fully engaged and agile in a social media environment means relationships with a wider array of interests, occurring at a much faster pace, and in a space where information is often fleeting. And the AHA has changed to meet that challenge, by allowing staff of varying degrees of professional expertise to participate in discussions and serve as content creators who can address the many different audiences of the Association.

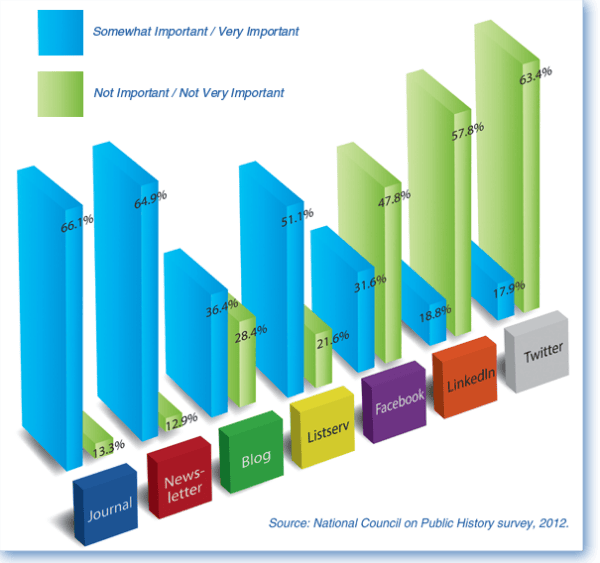

As a recent NCPH survey shows, historians draw from a wide array of information sources (fig. 2). Looking ahead, the AHA is working to develop new spaces within the AHA website that will allow members to create content and participate in scholarly and professional exchanges-with their peers or the world at large. Some indication of this new mission is evident in the recent teaching initiative described by Patty Limerick (“Tipping Points in Teaching: A Call for Collaboration,” Perspectives, December 2012). But it will clearly take more time before the discipline’s conception of scholarship-both its form and how to assess its value-realigns to fit with the changing patterns of communication.

Figure 2: Perceived Value of Information Sources According to Public Historians

Whether it has been revolution or evolution, at the end of my 24 years, the AHA’s publishing and communications program has fundamentally transformed. Many of my friends in the Twitterverse and blogosphere are quick to suggest that it hasn’t changed enough, while many of the AHA’s traditional members maintain it has changed too much. As I shift from directing these efforts to a new role as an AHA member and online participant, I look forward to seeing where the Association goes from here.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at a panel on “Scholarly Societies in the Humanities: New Models and Innovation,” sponsored by the Scholarly Communication Program and the Digital Humanities Center at Columbia University.

Notes

- Robert B. Townsend, “How Is New Media Reshaping the Work of Historians?“ Perspectives on History (November 2010). [↩]

- The findings from the survey of NCPH members can be found at Robert B. Townsend, “Speaking of the Survey (Part 3): Diversity and Challenge in Public History’s Information Landscape,” History@Work. [↩]